Justyna Burzynska

Arts Policy and Management,

Birkbeck, University of London, UK

Email: j.burzynska@fashion.arts.ac.uk

Web: To Be Announced

Google Scholar: To Be Announced

ORCID: To Be Announced

Twitter: To Be Announced

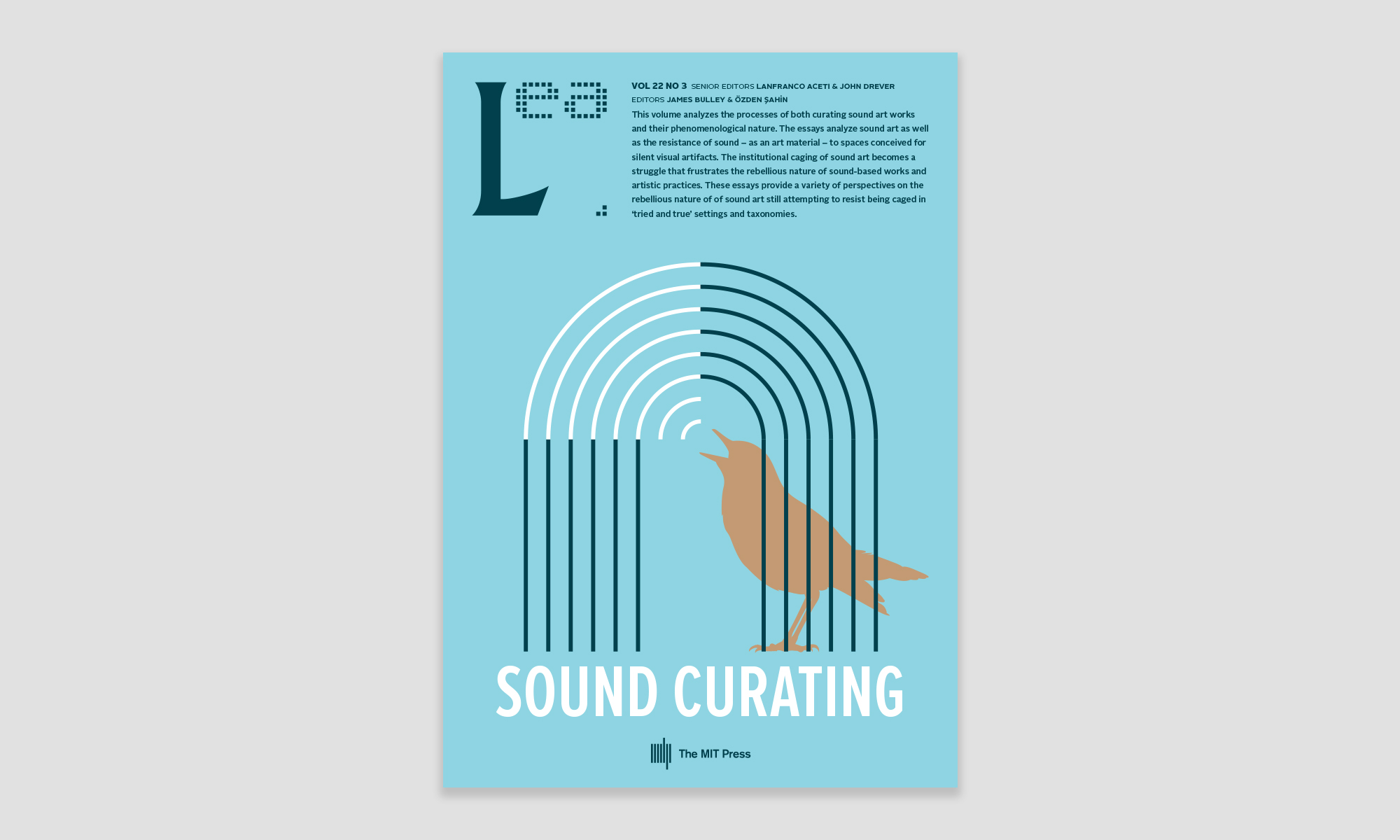

Reference this essay: Burzynska, Justyna. “Curating Sound Art: A London Perspective.” In Sound Curating, eds. Lanfranco Aceti, James Bulley, John Drever, and Ozden Sahin. Cambridge, MA: LEA / MIT Press, 2018.

Published Online: December 15, 2018

Published in Print: To Be Announced

ISBN: 978-1-912685-55-4 (Print) 978-1-912685-56-1 (Electronic)

ISSN: 1071-4391

Repository: To Be Announced

Abstract

This essay explores the practical implications of sound-based works entering the gallery space in London in recent decades. Issues with the term ‘Sound Art’ are discussed, and a review of sound art’s relationship to the arts institution is carried out. The common ground between, and overlapping concerns of ‘New Media Art’ and ‘Sound Art’ are investigated. Curatorial concerns are drawn from interviews conducted with members of London based organisations: Mark Jackson of Image Music Text Gallery, Matt Lewis and Jeremy Keenan of Call & Response, and Helen Frosi of SoundFjord. Independent sound artists Paddy Collins and Pia Gamberdella of Brown Sierra make further contributions to the discussion. In this review of the vibrant and rapidly evolving sound art scene in London, I will confront the curatorial factors that seem to deny sound art works a wider distribution and audience, describing the ways in which these problems have hindered sound art’s inclusion in wider contemporary art discourse.

Keywords: Arts management, sound art, curation, London, galleries, arts institutions

Introduction to Curating Sound Art: A London Perspective

Recent years have seen an increase in the popularity and institutional recognition of new media works, including sound art. In 2000, the Hayward Gallery’s Sonic Boom was the first exclusively sonic exhibition to be held in a major London art institution, and the Turner Prize awarded to Susan Philipz for Lowland Away in 2010 considerably raised the profile of sound art as a discipline. Nevertheless, problems with conceptualizing sound art as a distinct medium, and the technological challenges its exhibition represents, have perhaps meant that it still remains a somewhat niche art-form. This article will give a London perspective on the growing relevance of sound art, but also on the logistical curatorial challenges it continues to pose. After exploring some of the terminological and conceptual issues raised by sound art’s newfound cultural and institutional prominence, I will explore the more practical and curatorial issues which were raised in my interviews with London-based curators and practitioners, principally Mark Jackson from Image Music Text, Matt Lewis and Jeremy Keenan from Call & Response, and Helen Frosi from SoundFjord. In contrast to the problems sometimes faced by large-scale galleries in exhibiting sound works (an institutional bias towards the visual, inadequate acoustic spaces, the default use of headphones, disorientated audiences and a lack of internal technical and curatorial expertise), my interviewees have all had some level of success in finding ways of acclimatizing audiences to an innovative presentation of sound in specifically tailored spaces or technological mediums. Their expertise reveal several different approaches for curators and artists to consider for the continued development, support and exhibiting of sound art into the future.

Terminology

David Toop posits that “at this point in history, music and other media overlap and hybridize in unpredictable and unprecedented ways.” [1] Morton Feldman described his practice as being “between categories – between Time and Space, between music and painting, between the music’s construction and its surface.” [2] Quotes of this kind hint at the shifting terrain in which sound art finds its roots, conveying an in-betweenness that causes difficulty in defining what sound art is or what it could be. The term ‘Sound Art’ is contentious even within its own community: the majority of practitioners and curators that I have interviewed find the term to be reductive in describing their varied practices. Attempting to define the field of Sound Art is often a means of differentiating it from music. Matt Lewis of the sound collective Call & Response suggests that it is a way of “distancing the practice from music making so that it is approached in a more conceptual way” [3] and that it can remove the “baggage of the entertainment industry”, [4] a commercialism that is often unwelcome within the cerebral gallery environment. Toop suggests that “the difference lies in the ultimate aim” [5], which curator Helen Frosi expands: in contrast to music, sound art is “on a different conceptual plain – working with a different language and for different motivations and purposes.” [6] For example, in London based artist Graham Dunning’s ongoing project Music By The Metre, music is composed and the work can be performed, but Dunning’s Industrial Painting and the Situationists turns the compositions into “a comment on the commodification of avant-garde and leftfield musics and sound art”. [7] By inserting works into art spaces and discourses, rather than those of the entertainment industry, and by implicitly or explicitly building on the ideas and provocations of art history, sound becomes conceptualised as a distinct artistic medium.

The use of the word ‘Art’ within the term ‘Sound Art’ seems to place it in the contemplative setting of the art gallery, inviting its constituent works and practitioners into a constructive discourse with the fine arts. Although many find the term insufficient and vague, it does have a certain utility in practical discussions. It aids curators in succinctly portraying types of work to colleagues when planning and executing appropriate manners of exhibition. The term also helps the curator in disseminating information about the work publicly – its simple form can be used in promotional material to convey the general parameters of the work, rendering it intelligible through literature.

The difficulty in summing up an emerging practice frequently lauded for its interdisciplinarity poses problems for both the curator and the arts institution, especially when considering where to physically and philosophically place sound art. Yet the fact that a discipline can simultaneously exist in different cultural spheres at the same time can be tactically used to gain a wider exposure to varied audiences and exploited to gain a broader array of financial support, not only from within the arts, but from the sciences, music, architecture, crafts and elsewhere.

The Arts Institution and Sound Art

It is often the case that the cultural structure an artwork is situated within dictates its audience and reception. Artist Christian Marclay describes a personal delineation between art and music structures, stating that as a student “he felt a lot more energy coming out of the music world than from the art world.” [8] Marclay chooses to perform and exhibit regularly within a gallery setting, positioning himself and his work clearly amongst art world structures. He has, however, observed problems in relation to this aspect of his practice: “overall art world structures aren’t ready” for sound art “because sound requires different technology and different architecture to be presented.” [9] This is still the case in the present day: in many gallery spaces, curators simply do not meet the technological and architectural needs of sound art works. My interviews suggest that spaces adept at showcasing the visual may be inadequately suited to setting up and maintaining sound art works, lacking the necessary on-site technical expertise. Further problems are caused by venues’ poor acoustics, or difficulties in the positioning of pieces – many large galleries were either formed in, or followed the nineteenth-century model of seeing buildings as merely receptacles of art works, large, pre-existing spaces where works could be simply hung and arranged. Contemporary mixed media works often demand a more flexible and symbiotic relationship between works and the spaces which house them to properly support these evolving art forms. Overall, however, When discussing the curatorial issues surrounding sound art, there was one issue that each of my interviewees reiterated: the privileging of the visual within the art gallery. Each raised concerns as to how an art audience ‘views’ sound, and whether indeed they should. This is an issue that cannot be ignored in the curation of sound art. The established viewing habits of audiences alter the reading of sound-based works, especially when they are encountered in what is seen to be a visual arts setting.

The sound artists Brown Sierra often find themselves frustrated by the reservation and lack of interaction amongst their audiences when they perform in galleries. Established audience behaviours of quiet contemplation in the visually dominated gallery environment often jar with the movements and noises generated by sound works and performances. Marclay notes that there can be a division between music and art audiences, causing confusion when the work blurs or questions the boundaries between the two: “I’ve always tried to break these divisions. Some people just listen to music; others just look at art. Some do both but they don’t do it in the same place.” [10] Although a generalisation, Marclay’s statement hints at a compartmentalisation of the senses within the gallery, something that, if not considered carefully, can become an obstacle in presenting sound-focused works within the arts institution.

One method of surmounting this barrier, common in recent years, has been the use of visual cues alongside sound works – an effort to first sustain the audience’s attention visually, and to then draw them towards a sonic sensibility. However, as Matt Lewis suggests, this can be both patronising and lead to a thoughtless “visual element tacked on” to the sound work. He points out that “there’s always a visual element. It’s there, you are in the space, there’s stuff happening, there’s the visual element.” [11]

Sonic Boom

David Toop alludes to the notion that a friction will always exist in the curation of sound-based works within arts institutions. In his introduction to the large-scale sound art exhibition Sonic Boom, he describes sound as “a medium with very particular and sometimes very difficult characteristics.” [12] In June 2000, Toop curated Sonic Boom at the Hayward Gallery, London. His stated curatorial aim was to create an exhibition where the “work should be made with the spaces of the Hayward Gallery and the demands of a group exhibition in mind.” [13] To achieve this, Toop explored the use of sound bleed to emphasise the cacophony of modern life. Sound bleed pertains to sound sources from different pieces mixing, rather than being isolated. The viewer also mixes the sound by their movement through the space. In the exhibition catalogue, Toop is thanked for helping the Hayward Gallery leap into sound, but it is telling that there has been no such high profile art show dedicated sound at the Hayward Gallery since. This suggests that, whilst sound is gaining increased recognition as an art form, it is still often considered somewhat too niche for a large institution to regularly engage with. The large amounts of moving parts and expertise required to set up and run such a show also inevitably puts a financial and technical strain upon the institution. Lastly, the unexpected format of shows like Sonic Boom can leave audiences not knowing how to navigate these large-scale spaces, ones in which they are used to viewing visual works. In the following interviews, we will investigate various artists’ and curators’ attempts to aid the public’s reception and navigation of sound works.

Furthermore, the curator Lina Dzuverovic suggests that whilst notable sound art shows held by large art institutions are a “significant move toward institutional engagement,” this could still remain a superficial platform that may “not guarantee profound and long lasting institutional support.” She proposes that arts institutions create a more sustainable support system by “producing, commissioning and collecting” [14] sound works. In recent years, despite a marked increase in both the commissioning and collecting of sound-based artworks, it is interesting to note that, from the cross section of large arts institutions in the UK who have produced sound art shows that I have reviewed in my research, all of them enlisted external curators. This indicates a reticence towards investing in the long-term curation of sound-based work, and reiterates the fact that curating sound requires a skill-set and knowledge of sonic architecture that is rarely found in traditional visual arts curatorship.

Raising the Profile of Sound Art

Interest in sound art has increased considerably over the past two decades. In 2010, mainstream awareness of sound art in the UK was facilitated by Susan Philipz’s Lowlands Away winning the Turner prize. The prestige of Philipz’s Turner prize triumph generated a great deal of interest and critical acclaim for sound art, and it is hoped that this will culminate in both an increase in sustainable institutional support and its inclusion in a wider critical arts discourse, both of which will aid sound art’s development. In conforming to the protocol of presenting Turner Prize nominees in a gallery setting, Lowlands Away was installed into Tate Britain for the awards. This was a curatorial choice that diminished the intent of the piece: a site-specific work for which location and environmental chance were integral. This suggests wider difficulties in adequately bringing localised, environmental sound works to a wider, international audience.

The fact that dedicated sound art courses have been developed in London, most notably at London College of Communication (LCC) and Goldsmiths, indicates that the practice is being accepted as a cohesive discipline and that practitioners of sound art might require knowledge that is not supplied in established fine arts courses. However, the merging of the Sonic Art and Fine Art degrees at Middlesex University indicates a move towards an arts education with a broad philosophical and conceptual base, one that is not medium specific. These contrasting parallel developments in the positioning of sound art in higher education reiterate the in-betweenness of sound in the arts at present, as educational institutions grapple with where best to situate and approach sound art. The balance between sound art’s technical, medium-specific demands, and the desire to render it more accessible and widely received by inserting it into wider cultural debates and institutional structures, is a difficult one to strike.

As Matt Lewis has noted, sound-based work is no longer a novelty within the arts: things are changing fast, and art audiences are becoming accustomed to sonic experiences in the gallery. As a result, the durational nature of sound works, which tend to require extended periods of attention from audiences, may now be less of an issue than it has been in the past. [15] This greater attunement to the sonic qualities of works could also begin to impact the reception of works considered to be primarily visual. Regarding the profile of sound in the traditional gallery space, Mark Jackson of IMT gallery points out that “there is something that people ignore a lot of the time, which is the presence of sound within a visual arts exhibition.” [16] Although these incidental sounds are not necessarily integral to the pieces on show, they cannot fail to inform the auditory experience of the audience in attendance, and this is an aspect of curatorial practice that requires further practical consideration and discussion.

Parallels with New Media Art

The developments in the curation of new media art provide an interesting parallel to those of sound art, and there are a number of resonances between the two areas. The growth in exhibition of new media based artworks has tested and expanded the curatorial and archival provision within many arts institutions. By considering the insights made by its critics, theorists and practitioners, we can adopt this alternative frame of reference and apply it to the situation of sound art: how can the contemporary curator “engage with new artistic practices made possible by such technologies, many of which present their own particular challenges in terms of acquisition, curation and interpretation”? [17]

As technology increasingly defines how we organise and structure our lives and culture, it is necessary for the art gallery to keep pace. However, engaging with new technologically based art forms poses complex issues as to how to collect, conserve and financially sustain such work. The ephemerality and fragility of any technology complicates the valuation of sound works, and the maintenance of the works over time can render any attempted commodification impractical. Yet despite these challenges, there are ways of creating revenue from the exhibition of sound art. Recent years have seen a proliferation of unique digital editions, limited run publications and ephemera, and paid ticketed artist talks, workshops and performances produced to supplement and sustain an exhibition.

As technologies evolve and one form surpasses another, new media artworks are being produced in formats that will swiftly become obsolete. The conservation of these works has financial implications for the institution, and in recent years much discussion has gone into how and what institutions should collect in such a fast-changing environment. The ZKM institution in Germany has taken up this issue with revisions to their archive and collections policies and in their collaborative work on the IDEAMA project, initiated in 1988, which aims “to preserve the most important and most endangered early works of electroacoustic music.” [18] As yet, however, there is no comparably large institution in the United Kingdom that has a remit to support sound art in this way, something that can be attributed to its still relatively marginalised place within the art world, its ill-defined meaning, and the general uneasiness amongst its own practitioners to commit to it as a defined practice. One high profile piece of sound art that began in London at the turn of the Millennium and which seeks to deal with these issues conceptually and practically is Jem Finer’s Longplayer, a site specific piece at Trinity Buoy Wharf that is designed to play for a thousand years. It was “created with full awareness of the inevitable obsolescence of this technology, and is not itself bound to the computer or any other technological form.” [19] From the moment of its conception, Finer considered how support a piece of such extreme duration. Subsequently, Longplayer has its own trust, founded to consider and develop plans to accommodate the work over time. A Longplayer app has been developed as “one point in a community of listeners stretching through time and space, across many lifetimes.” [20] Users can listen to the piece anywhere, a key aspect of the brief which stipulated that Longplayer should be able to be played by any technology as it evolves over time.

Technological developments therefore open new possibilities for the preservation and dissemination of sound works. This is especially important in a context in which institutional galleries are often hindered by a fear of the unknown, lacking in technical support facilities, and forced to consider novel related methods to support the un-commodifiable work of new media and sound art practitioners. Nevertheless, galleries remain important sites of artistic consecration and the primary venues many audiences first encounter new works. In the following interviews, artists and curators examine the various aesthetic and logistical challenges of presenting sound works both inside and outside gallery spaces.

Mark Jackson, Curator of Image Music Text Gallery, Cambridge Heath, London

IMT is a gallery space that exhibits emerging and established artists working across all media, specialising in installation, sound art and multimedia art. Mark Jackson is also an associate lecturer at LCC on the sound art program and at Southampton Solent University on the fine art program.

Dead Fingers Talk: The Tape Experiments of William S Burroughs (28th May – 18th July 2010)

When discussing the curation of the group exhibition Dead Fingers Talk, Jackson stated that “sound has to be acknowledged as a force that cannot be contained” and the “basic physics of sound” and the architecture within which the piece(s) are to resonate must always be taken into consideration. In practical terms, “you can’t completely block off sounds,” and, following this, sometimes you may not want to. Similar to Toop’s methods for Sonic Boom, the ‘promiscuity’ of sound was purposefully exploited in the exhibition, honouring the idea of William Burroughs’ cut up tape experiments. Within the exhibition, Jackson describes how the “interruption and obliteration” of one sound by another created intentional cacophonies. When planning the exhibition, which involved a number of artists responding to Burroughs’ work, Jackson selected practitioners from across the music and art worlds because he aimed “to reinforce that sound art doesn’t have to be validated as a cohesive discourse,” a statement that both demonstrates the easy cross-disciplinarity of the practice and highlights the potential inadequacies of the term in itself. When I asked Jackson where he would place IMT gallery within the cultural sector, he stated: “IMT represents a way of doing things that is associated with the art world,” yet he also notes that there is an onus in his programming on aiming to “stretch what is possible in terms of the sound world.” [21] It is perhaps in the direct collision of these two worlds that some of the most vital curatorial experiments with sound art can be made.

The Sonic Body, Brandon LaBelle (22nd April – 22nd May 2011)

In his curation of Brandon LaBelle’s solo exhibition The Sonic Body, Jackson and LaBelle intended for the gallery space to look “reasonably untidy”. A curatorial decision was made to expose the materials by which the sounds were being produced: headphones, speakers, wires etc. Jackson also felt it important to preserve the “simplicity of the environment without being overburdened by visual cues.” [22] During the exhibition, Jackson found that audience members spent long durations of time in the space, a testament perhaps to the careful staging of the works, which were structured in two visually and spatially straightforward, self-explanatory settings.

Sound Arts at London College of Communication

Jackson has also curated the end of year shows for LCC’s Sound Art Masters program. These exhibitions present a unique range of curatorial challenges. Each year he must create a cohesive exhibition from a large amount of differing sound works whilst being subject to strict spatial, financial and logistical constraints. In dealing with these problems, Jackson has adopted a number of techniques, including the division of larger spaces with temporary partitions to allow each work a separated sonic architecture. Visually and architecturally, the partitions and booths can define the attributes of the work itself, and this is discussed carefully with the artist. Jackson often considers in detail the visual aspect of the exhibition: in 2011 the showcase had a distinct curatorial direction informed by “taking something which is firmly from a visual arts world, and seeing how sound artists adapt to that”. [23] Within the exhibitions, Jackson often solves the issue of unwanted sound bleed between works by the careful use of headphones, allowing the sounds to be both contained and clearly directed. Whilst certain problems surrounding the use of headphones will be discussed below, during the 2013 exhibition Jackson successfully used a staggered playback of pre-recorded pieces in conjunction with a program of performances over the course of a week, with a small selection of pieces on headphones. This meant that the audience’s experience varied dependent on the time of the day they arrived at the gallery. Whilst preventing viewers from being able to experience the whole show in one visit, this durational approach supported the particular spatial needs of the works and provoked added concentration from the audience when listening to the pieces in the exhibition.

Other Spaces for Sound

Jackson suggests that the gallery is not an optimal place to exhibit sound art: its acoustic and technical architectures are not designed with sound in mind. Maybe there simply is not a best place for sound, he contends, since sound by “its very nature has to adapt to different contexts.” [24] Having considered the situation of sound-based exhibitions experienced within conventional gallery spaces, let us turn to thinking on alternate sites for sound art exhibitions. Some of the most innovative sound-based curation exists between or outside of physical locations. In 2011, independent arts radio station Resonance FM was installed into Raven Row gallery as part of the Gone With the Wind exhibition, curated by Ed Baxter. In 2012, the Institute of Contemporary Arts launched Soundworks, an online showcase of sound art that aims to embrace “the ephemeral nature of sound” and to present “an online platform that doubles as a virtual exhibition space.” [25]

Non-geolocated exhibitions have advantages, including a much wider accessibility and greater autonomy for the audience, who become free from the conventions of the art gallery or institution. But the drawbacks must also be recognised and explored by curators: further work must be done to investigate the impact this can have on the experience of an exhibition. It is, for example, the case that the playback equipment and acoustic environment that the listener encounters the material in plays an undefinable role in how the sound is received — what therefore, does this mean for the intelligibility of the work, or the exhibition as a whole? Christian Marclay believes that sound’s democratic strength means it is “so easy to share that you don’t need an art institution to tell people what to listen to.” [26] Here, whilst Marclay is questioning the power role of the institution in defining what is listened to, I would add that the institution and its curators can play a vital role in rigorously exploring the processes surrounding how sound-based artworks are listened to, helping artists and audiences to explore new methods for experiencing sound-based artworks.

Matt Lewis and Jeremy Keenan of Call & Response, a London Based Independent Sound Art Collective

Call & Response (C&R) was set up in response to a lack of project spaces able to support multichannel sound works, and also as a means of promoting sound art education. Throughout my research, I discovered many artists and curators who have set up independent enabling structures to curate and promote sound. This was often attributed to the unsatisfactory treatment and understanding of sound works in conventionally established galleries. C&R highlight that curating sound can be “as much about the space as the sounds being produced,” [27] and they question whether conventional, visually-focused galleries can ever be suitable spaces for sound art exhibition.

As an independent collective, C&R have had mixed experiences when working with different types of arts organizations to curate and exhibit sound works. They have found most institutions to be highly enthusiastic to put on the work, but lacking an adequate understanding of the technical requirements necessary. This lack of knowledge and resources has often led to fraught working relationships. C&R have unsurprisingly found it easiest when working in places more used to hosting sound, such as their curation of an 8-channel audio programme at the Roundhouse in London for NetAudio 2011. The on-site technical expertise and architectural acoustics of the Roundhouse allowed C&R to install their work to its fullest potential. In addition to large-scale venues of this kind, they have also found working with smaller artist-run spaces to be beneficial. C&R cite their launch at the James Taylor Gallery in 2011 as an example. Passion for the project was backed up with practical technical support and informed discussion from the artist-curators. In recent years, C&R have operated across spaces in London and Europe to realize their projects and workshops. In September 2014, they obtained a space of their own, in Deptford, South East London, from which they host residencies, installations and workshops, allowing them a control over their sonic environment that provokes exploration of novel curatorial strategies.

Headphones

In the interviews I conducted around the presentation of sound art in gallery spaces, the prevalent use of headphones repeatedly cropped up. The majority of curators and artists I spoke to found the use of headphones in contemporary sound exhibitions to be lazy and poorly considered, simply a way of avoiding acoustic issues in the space. Matt Lewis felt that the core multi sensual nature of sound within space is lost when headphones are worn. [28] Jeremy Keenan elaborated, noting that the use of headphones “negates the possibility for inter-subjective experience.” [29] Curators must consider that the internalising of sound through use of headphones may detract from or confuse the intent of a work. There is a fatigue which comes from seeing such equipment repeatedly installed, which might make the audience reticent to put them on in the first place, or ignore them entirely. Sound artists Brown Sierra, whose practice embraces the spatial quality of sound, find putting on headphones in an arts environment often an unsatisfactory and awkward experience. [30]

Other times, however, headphones are integral to the piece, as in the work of Janet Cardiff and Christina Kubisch. Cardiff has made works where she stipulates that her audio must be listened to with headphones. In Her Long Black Hair (2005), her headphone-based narration and the exterior sounds of the Central Park location become a method of creating a reflective, ever-changing narrative. In Kubisch’s Electrical Walks (2004–2015), specially designed headphones pick up electrical fields through electromagnetic induction, rendering them audible. It is notable that both Cardiff and Kubisch commonly utilise headphones in situations that are removed from the gallery space. The headphones become a portable medium that adds new perspective to the act of walking and exploring, and they become a key conceptual aspect of the work. Cardiff and Kubisch’s use of headphones highlights the care with which curators must consider their impact, and how they can alter an audience’s experience of both site and space.

Helen Frosi, curator of SoundFjord, London

Initially an artist-run space that started in Seven Sisters in 2009, SoundFjord, run by curator Helen Frosi, was “founded to redress the current lack of exhibiting space exclusively for works of sound art” [31]. Frosi states SoundFjord’s curatorial drive as being: “sound and its power for practical, intellectual and philosophical articulation between the nexus of performance, music / sound production and visual art and beyond into scientific, architectural and psychological study.” [32] SoundFjord existed as a physical space from 2009 up until the summer of 2013. Frosi has since described her curatorial strategy as “nomadic”, working “across venues and locations as much as possible to encourage others to work with them to extend their curatorial tendrils.” [33] Taking up this strategy fully gave SoundFjord the opportunity to share resources, skills and knowledge across sites in the UK and internationally. Frosi describes this openness as integral to SoundFjord’s mode of operation. This way of working is also partly a survival strategy. In a time when the arts have seen steep funding cuts, sound art has been particularly affected due to its outlying status within the arts world. Frosi furthers that the move away from having a static space is due in part to the site-specific nature of many works:

“sound works are often very site-specific, or at least site sensitive, so having a space was only good for workshops and experimental one-off events. Being nomadic is challenging in many ways, but I think it fits better with the ideals of SoundFjord.” [34]

When Frosi and I discussed the challenges that sound art faces within the arts as a whole, she mentioned that sound art “does not have the codification and signification fixed in stone as those found within visual arts,” [35] and this may restrict sound art’s entrance into the conventional gallery. She mentioned her experience of poorly presented sound works, including turning the piece up too loud; sound systems that “lack the clarity that the works justify”; [36] and placing works in places of transition, such as halls and stairwells. All of these curatorial decisions can negatively affect the audience’s perception of sound-based works. She suggests that late evening events at galleries “where music and entertainment are often confused with sound art” [37] can be problematic, too. She also makes a point that sound art’s incorporation into the gallery for its “cool factor” can lead to some ill-advised curatorial decisions. The fact that audiences are not seen to be physically responsive to works may deter galleries from putting on other such works, “especially if complicated technical knowledge and expensive equipment has been necessary.” [38]

Frosi sees SoundFjord as part of the gallery system, yet emphasises that they “exist to promote artists in a philanthropic way, not simply on a commercial level.” [39] As for their curatorial direction, Frosi states:

“We will work on our projects independent of how sound art is perceived by the general public, so long as, for us, it remains a genre that is conceptually rigorous, and incites questions and an alternative look at the world.” [40]

This ability to be collaborative, to take risks and to work semi-autonomously from the conventions of the gallery architecture is beneficial for independent arts organisations when curating sound art exhibitions. However, it comes at the price of financial uncertainty: SoundFjord is mostly self-funded with some support from donations and arts funding schemes. The trepidation of larger arts institutions to take sound art on in their programming means that it is often up to the smaller independent organisations to champion experimental works and novel curatorial methodologies before they become inducted into large arts institutions. It is a symbiotic relationship, and both large and small arts institutions could benefit from fostering it. The larger institutions could provide sustainable support for the smaller, whilst learning from the innovative methodologies being shared.

Conclusion

The expanding independent gallery scene in London has eased sound art into popular consciousness and the cultural mainstream. As audiences are increasingly exposed to sound-based work in galleries, they have become conversant with the discipline. However, the problem of classifying what sound art is continues to be a complex and often reductive task. The lack of an agreed working definition, even in a broad, inclusive sense, causes problems when considering how works should be culturally situated, curated, and how constructive dialogues can be developed around the unique curatorial issues that pertain to its practice and exhibition.

From the interviews conducted during my research, it became clear that curators must focus from the outset on the site-specific nature of most sound-based works, rather than merely installing sound art in a gallery space using the well-trodden conventions of the visual arts. Much can be learned from examining the problems that face other disciplines and their practitioners, particularly the similar issues facing new media artists and curators, and more must be done to create dialogues and theorisation in this area. Due to the nature of the technologically focused society we live in, it is of paramount importance that art institutions keep abreast of technological innovations. By employing in-house technicians and curators to support sound-based exhibition, museums and institutions would gather a base of transferable skills that can be applied to technological developments across new art forms.

In recent years, the role of the curator has expanded, requiring a working knowledge of the technical aspects of installing sound into a gallery setting to ensure that such pieces can be realised in the way that the artist intended. This is not, however, purely the work of a curator or gallerist; contributions must be made from the artist themselves, ensuring that their work is realised in an appropriate form. The exhibiting of sound-based work can create an important reflective platform from which to question our current manner of art exhibition. Indeed, when describing the challenges that the exhibition of sound-based work poses to her profession, curator Lina Dzuverovic states that:

“When sound begins to travel around spaces originally designed to display and preserve art objects such as paintings and sculptures, the very nature of the institution is in question – their role, economic models, exhibition and preservation strategies.” [41]

Dzuverovic demonstrates the powerful potential of engaging with an art form that questions the status quo. Sonic works force both art institutions and curators to reconsider and renegotiate established practices. Their exhibition requires the creation of novel strategies that evolve from the experimental curatorial practice of independent curators and galleries. There is a need to ensure sustained support for these independent curatorial innovators, and to carefully consider how larger institutions might learn from them, ensuring that sound-based works are exhibited and preserved in a more sympathetic and cohesive manner in future.

Acknowledgments

With thanks to Jo Burzynska, Dr. Malcolm Riddoch, Robert M Fenner, Dr. Adrian May, Call & Response, SoundFjord, Image Music Text Gallery, Brown Sierra and Birkbeck, University of London.

Author Biography

Justyna Burzynska is an illustrator and curator currently residing in London. She completed a masters in Arts Policy and Management at Birkbeck in 2011, specialising in curation. This paper is an extracted and updated version of her thesis Curating Sound: Issues of Displaying Sonic Art. She has a diverse artistic output spanning visual arts, music and writing. She trained as an illustrator at Camberwell College of Art and has had illustration work published in Writing Around Sound, Dazed & Confused magazine and numerous small press publications. In 2016 she collaborated with Hannah Thompson, Sound Artist in Residence at Senate House Library, producing imagery to publicise the year long project. She produces non-music with artist Nurvuss, with releases on Desire Records, Pimpmelon and Aufnahme + Widergabe. She curates noise and music events in London under the banner Club Jigoku with partner Robert M Fenner. She curated London: A Sonic Fragment at The Auricle Sound Art Gallery in New Zealand in January 2015.

Note and References

[1] David Toop, Sonic Boom: The Art of Sound (London: Hayward Gallery Publishing, 1999).

[2] Alan Licht, Sound Art: Beyond Music Between Categories (New York: Rizzoli International Publications, 2007).

[3] Matt Lewis, Interview conducted with Matt Lewis of Call & Response by author, London,

2011.

[4] David Toop, ‘The Art of Noise’, Tate, 2005, http://www.tate.org.uk/context-comment/articles/art-noise (accessed January 10, 2014).

[5] Ibid.

[6] Interview conducted with Helen Frosi by author, London, 2011.

[7] Graham Dunning, ‘Music By The Metre’, Graham Dunning, 2016

https://grahamdunning.com/portfolio/music-by-the-metre/ (accessed December 13, 2016).

[8] Jason Gross, ‘Christian Marclay’, Perfect Sound Forever, 1998

http://www.furious.com/perfect/christianmarclay.html (accessed January 5, 2014).

[9] Alan Licht, Sound Art: Beyond Music Between Categories (New York: Rizzoli International Publications, 2007).

[10] Jason Gross, interview with ‘Christian Marclay’, Perfect Sound Forever, March,1998, http://www.furious.com/perfect/christianmarclay.html (accessed January 5th 2014).

[11] Interview conducted with Matt Lewis of Call & Response by author, London, 2011.

[12] David Toop, Sonic Boom: The Art of Sound (London: Hayward Gallery Publishing, 1999).

[13] Ibid.

[14] Lina Dzuveroic, “The Love Affair Between the Museum and the Arts of Sound. But Will it Last?” Axisweb.org, 2007, http://www.axisweb.org/dlFULL.aspx?ESSAYID=85 (accessed September 6, 2011).

[15] Interview conducted with Matt Lewis of Call & Response by author, London, 2011.

[16] Interview conducted with Mark Jackson by author, 2011.

[17] Charlie Gere, ‘New Media Art and the Gallery in the Digital Age’, Tate Papers, 2004, http://www.tate.org.uk/download/file/fid/7411 (accessed January 5, 2014).

[18] Zentrum fur Kunst und Medientechnologie, ‘IMA | Archive’, ZKM, 2014

http://on1.zkm.de/zkm/musik/archive (accessed January 5t, 2014).

[19] The Longplayer Trust, ‘What is Longplayer’, Longplayer.org, 2014, http://longplayer.org/what/overview.php (accessed January 5, 2014).

[20] The Longplayer Trust, ‘Longplayer iOS App’, Longplayer.org, 2016, http://longplayer.org/listen/longplayer-ios-app/ (accessed December 13, 2016).

[21] Interview conducted with Mark Jackson by author, 2011.

[22] Ibid.

[23] Ibid.

[24] Ibid.

[25] Institute of Contemporary Arts, ‘Soundworks’, ICA, 2014, http://www.ica.org.uk/projects/soundworks (accessed January 5, 2014).

[26] Alan Licht, Sound Art: Beyond Music Between Categories (New York: Rizzoli International Publications, 2007).

[27] Interview conducted with Matt Lewis and Jeremy Keenan of Call & Response by author, London, 2011.

[28] Interview conducted with Matt Lewis of Call & Response by author, London, 2011.

[29] Interview conducted with Jeremy Keenan of Call & Response by author, London, 2011.

[30] Interview conducted with Brown Sierra by author, London, 2011.

[31] Interview conducted with Helen Frosi by author, London, 2011.

[32] Ibid.

[33] Ibid.

[34] Helen Frosi, e-mail message to author, December 18, 2013.

[35] Interview conducted with Helen Frosi by author, London, 2011.

[36] Ibid.

[37] Ibid.

[38] Ibid.

[39] Ibid.

[40] Ibid.

[41] Lina Dzuveroic, ‘The Love Affair Between the Museum and the Arts of Sound. But Will It Last?’, Axisweb.org, 2007 http://www.axisweb.org/dlFULL.aspx?ESSAYID=85 (accessed September 6, 2011).

Bibliography

Gere, Charlie. “New Media Art and the Gallery in the Digital Age.” Tate Papers, 2004. http://www.tate.org.uk/download/file/fid/7411.

Licht, Alan. Sound Art: Beyond Music, between Categories. New York, N.Y: Rizzoli International Publications, 2007.

Toop, David. The Art of Noise, Tate Etc. issue 3: Spring 2005, http://www.tate.org.uk/context-comment/articles/art-noise

Toop, David, Fiona Bradly, Sophie Allen, Exhibition Sonic Boom: the Art of Sound, and Hayward Gallery, eds. Sonic Boom: The Art of Sound ; [on the Occasion of the Exhibition Sonic Boom: The Art of Sound, Hayward Gallery, London, 27 April – 18 June 2000]. London: Hayword Gallery Publishing, 2000.