Eef Masson

Assistant Professor, Media Studies, University of Amsterdam, the Netherlands

Email: E.L.Masson@uva.nl

Web: https://www.uva.nl/profiel/m/a/e.l.masson/e.l.masson.html

Karin van Es

Assistant Professor, Media and Culture Studies, Utrecht University, the Netherlands

Email: K.F.vanEs@uu.nl

Web: http://www.karinvanes.net/

Reference this essay: Masson, Eef and Karin van Es. “Encounters at the Threshold: Interfacing Data in Urban Space.” In Urban Interfaces: Media, Art and Performance in Public Spaces, edited by Verhoeff, Nanna, Sigrid Merx, and Michiel de Lange. Leonardo Electronic Almanac 22, no. 4 (March 15, 2019).

Published Online: March 15, 2019

Published in Print: To Be Announced

ISBN: To Be Announced

ISSN: 1071-4391

Repository: To Be Announced

Abstract

The mobile apps The Architecture of Radio and White Spots are exemplary of a contemporary strand of media art that explores the relations between data, their infrastructures, and our physical or lived environments. In this article, we use them to investigate the ways in which interfaces enable engagements with our data-saturated urban habitat, demonstrating in the process how they extend definitions of the interface as a ‘boundary zone’ or ‘threshold’. We argue that interfacing always happens at different levels simultaneously; technologically speaking (in the sense of the different layers of a ‘stack’ of computer protocols) but also metaphorically. In this piece, we identify three levels of interfacing, that serve in turn as the lens through which we examine how the apps facilitate interactions, and what sort of relations between the user, the city, and data or connectivity this entails. In the process, we pay particular attention to the interface’s productivity: the role it plays in shaping realities or worlds, but also types of user agency and subject positions. The argument we work towards is, that in setting up specific encounters, interfaces are revealing not only of how we understand technology but also of how we imagine our social world.

Keywords: Interfacing, data ubiquity, connectivity, data art, urban spaces, mobile apps, social imaginaries

Introduction

In her latest book, Code and Clay, Data and Dirt: Five Thousand Years of Urban Media, Shannon Mattern looks back on the first decade of this century, when users of mobile media and web-based services began to realize the dependence of their connections on invisible material networks. [1] At the time, she recalls, artists and designers increasingly also produced work that sought to make those networks visible. The first wave of projects primarily responded to a growing public apprehension of the possible health effects of invasive electromagnetic signals (a phenomenon, Mattern points out, reminiscent of the anxiety about wireless radio signals nearly a century earlier). [2] More recently, their work shifted attention to the relations between the ubiquity of data infrastructures and practices of surveillance and control. But it also betrayed concern with the constant connectivity those infrastructures invite or impose, and its psychological or socio-cultural implications.

A recent addition to this last body of work is The Architecture of Radio, a mobile application produced in 2015 by the Dutch information designer Richard Vijgen. [3]Using GPS, and processing data from global open datasets, the app makes visible the invisible data infrastructures that enable our practices of observation, communication and navigation. It provides a 360-degree visualization of what its associated website calls the ‘infosphere’: “an interdependent environment […] populated by informational entities.” [4] The image it generates shows nearby data ‘hardware’ (discrete elements of the relay infrastructure such as cell towers and satellites, but also physical access points, i.e. Wi-Fi routers) and the digital radio signals they emit. In doing so, it also simulates the density, as well as the movement through space, of the data flows they channel. The work draws attention to the presence of such flows in our physical surroundings and lived spaces. It shows where data originate and speculates on how they move around, without being visible or otherwise perceptible. [5]

A year after Architecture’s public roll-out, the work’s visualization functionality was integrated into another app, called White Spots. [6] White Spots was developed as part of a larger multimedia project involving also the documentary filmmaker Bregtje van der Haak and the visual artist Jacqueline Hassink. Unlike Architecture, this app strongly appeals to the user’s desire to (temporarily) escape from a condition of being perpetually ‘connected.’ Complementing the ‘network scanner’ with a map function, it invites users to “escape from the information flows surrounding us” by seeking out nearby places “off the grid”; that is, without connectivity. [7]

In Architecture and White Spots, the making visible of what otherwise remains covert results in a picture of hybrid urban/informational landscapes brought about by ubiquitous wireless technologies. Each app mediates between different dimensions or ‘layers’ of the city: physical and virtual (yet importantly, also material) or urban and informational. But simultaneously also between worlds connected and disconnected, urban and non-urban.

Neither of the apps explicitly designates connectivity as a specifically urban matter. However, each project makes its argument through a visualization designed to sensorially overwhelm the user. As internet connectivity on a global scale still suffers from an urban/rural divide, this is particularly likely to happen in cities, where coverage is sufficiently dense. [8] More importantly, both works invoke common associations between data infrastructure, connectivity, and the fabric of the urban. As Mattern observes, the “steel and concrete structures [of the contemporary city] serve as scaffolding for the installation of wired, wireless and satellite technologies, providing […] tenants with […] dead-zone-free connectivity.” [9] But they also stand for high population density and intense (economic) activity. This is particularly evident in White Spots, which appeals to its audience’s yearning for relief not only from the expectation of being constantly connected, but also from whatever else is innerving or exhausting about urban life. The app lures them toward spots that are ‘white’ in the sense of a freedom from data traffic, but by the same token, also from the much more perceptible – visible, audible, even scentable – traffics of people, vehicles, and other bodies involved in their daily wrought-up business.[10] In the process, it invites them to imagine the boundaries of urban space.

Key to both apps’ process of mediating between the city’s different ‘layers’ is the interface – as a technological given, but also, to speak with Branden Hookway, as a kind of relation or “site of encounter” (a notion we shall return to shortly). [11] Arguably, an encounter is staged between the user and each app, but also between the user and the various ‘layers’ and ‘worlds’ mentioned, and even between those layers and worlds amongst each other. Technologically speaking, both works, and especially their so-called ‘network scanners’ (their functionalities for visualizing data points and signals or streams), are difficult to pin down. As we shall explain, this is due in part to the rather complicated ways in which the images they produce overlay the worlds they provide information on, and in the process, ‘augment.’ But they are complex also in terms of the encounters they produce, and how they do this – whether those encounters are considered in terms of embodied experiences of data in urban space, or as invitations to reflect, or even act, upon the relations between data and the environments where they circulate.

In what follows, we investigate how interfaces enable engagements with our data-saturated (urban) habitat. Architecture and White Spots directly provoke us to take on this task. On the one hand, because they challenge us to engage with the indeterminacy that all interfacing involves: its perceptual ambiguity, but also the more conceptual ‘betweenness’ that takes shape in the mediation among different realities. [12] Our goal is to understand how they facilitate interactions, and what sorts of relations between the user, the city and data or connectivity this ultimately entails. But on the other, the apps also prompt us to rethink, more broadly, what interfacing means, and how it works at a time when the visible and invisible, material and immaterial dimensions of city and data permanently co-exist.

First, by way of introduction, we explore how media art more broadly engages with the topic that Architecture and White Spotsaddress: the omnipresence of invisible data, specifically in relation to urban space. Next, we discuss some ideas from interface theory that are productive to our analysis. We conceptualize interfaces as zones of mediation, where an encounter takes place between different entities. Subsequently, we argue that interfacing always happens at different levels simultaneously: different layers of a ‘stack’ of (computer) protocols, but also – we propose – levels in a more metaphorical sense. In the analysis that ensues, they serve as a lens, that helps us to reveal how interfaces are productive; for example, of distinctions between different dimensions of our experiential reality, but also of certain types of agency and specific subject positions. Focusing primarily on Architecture and White Spots, we demonstrate how interfaces are telling not only of how we understand technology but of how we imagine our social world. In the process, we extend common understandings of the interface, revealing its implication in the construction of social imaginaries.

Media Art, Ubiquitous Data, and the Urban

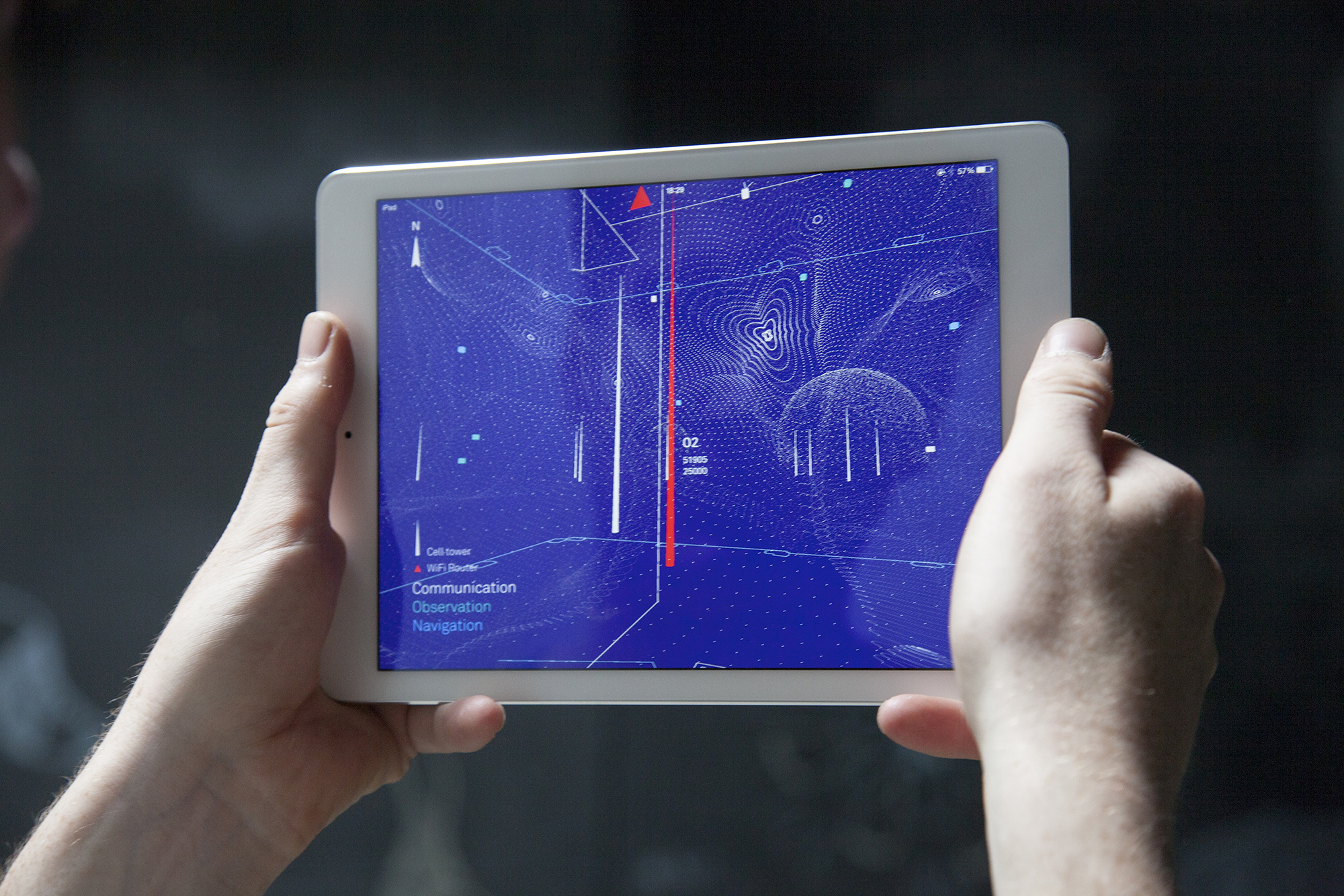

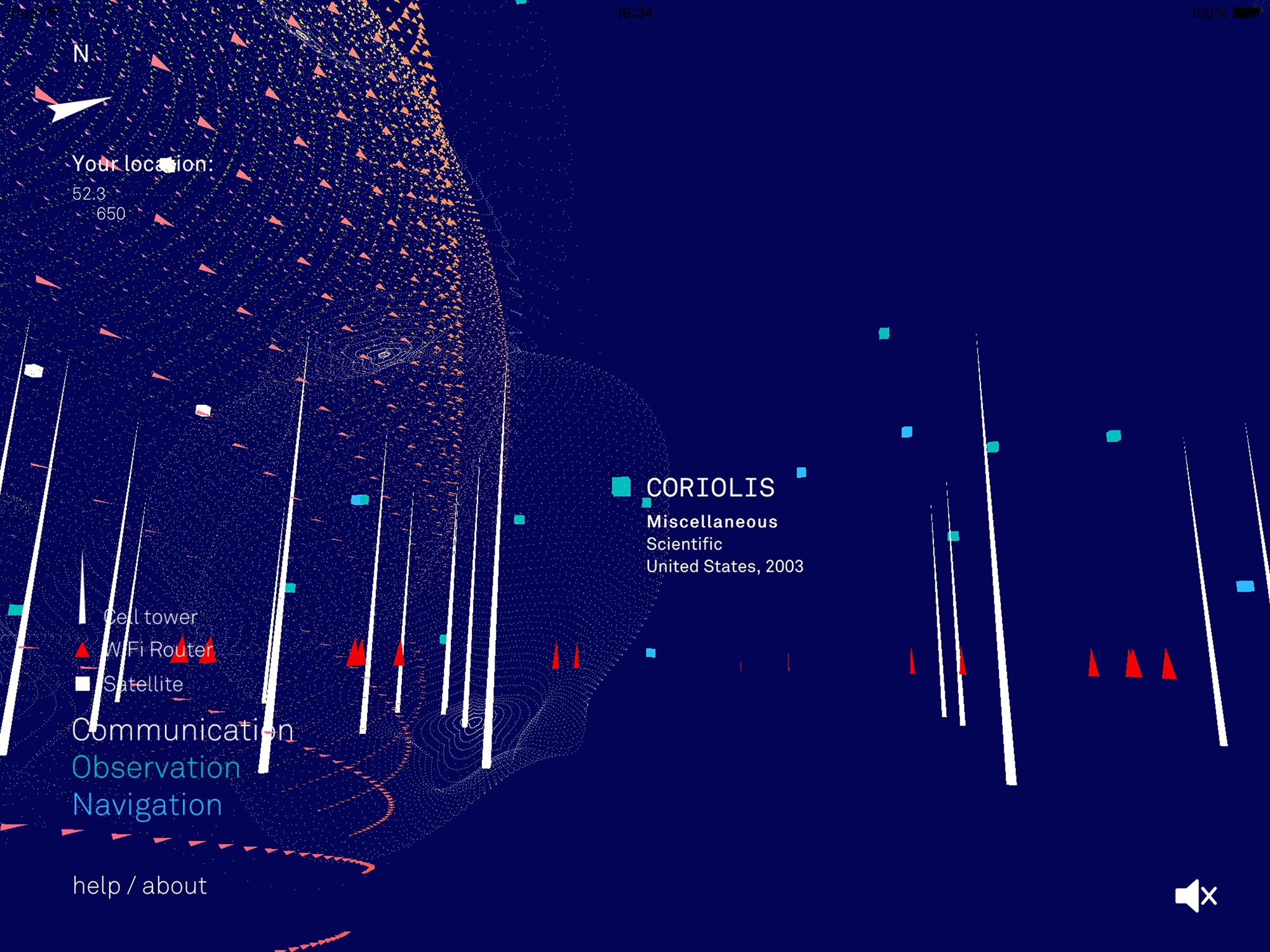

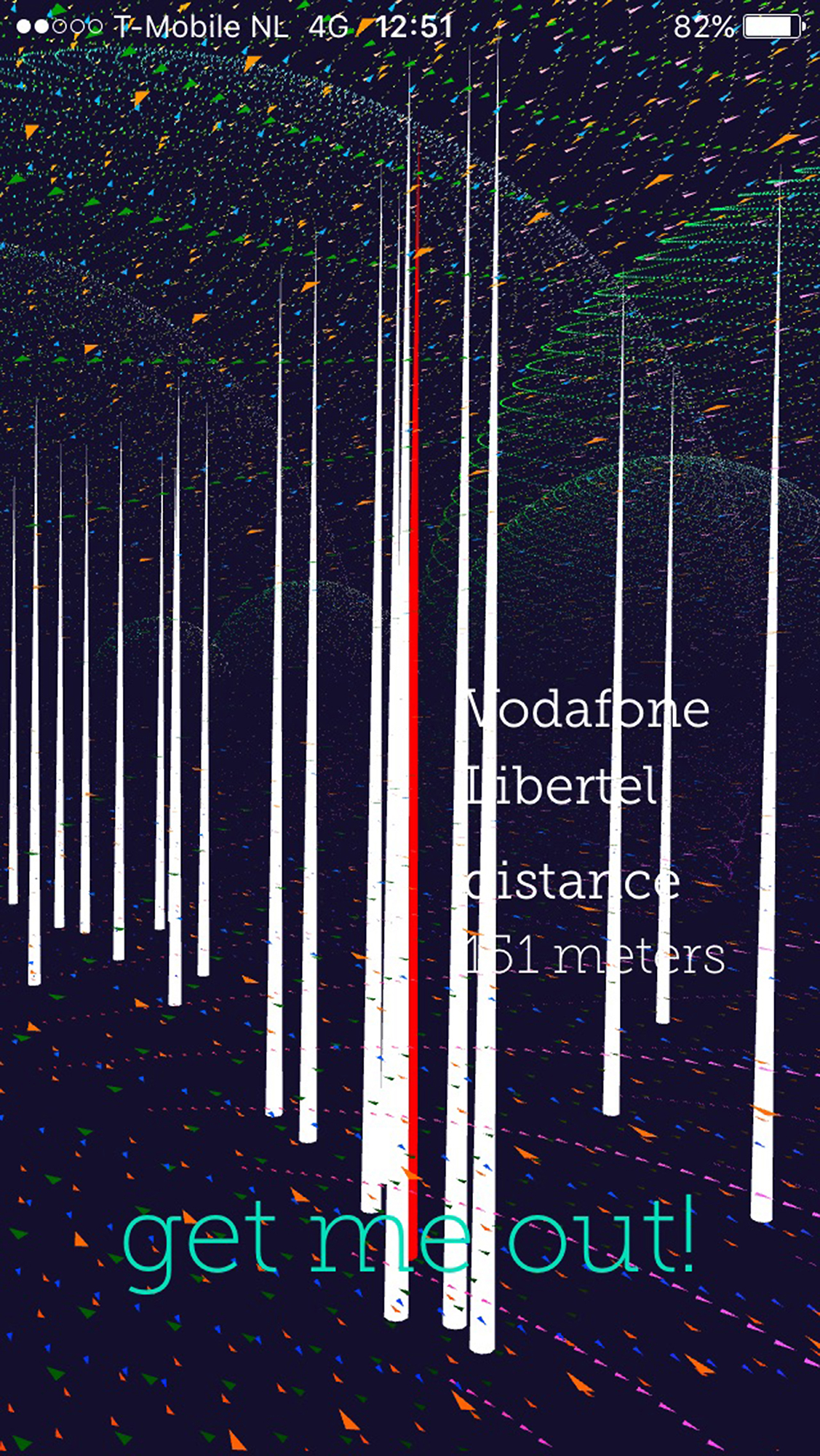

The network scanner function in Architecture and White Spots visualizes the physical nodes in systems for wireless communication, along with the signals they emit. The views it generates consist of a dark blue background, overlaid with specific combinations of geometric figures. In Architecture, which relies on multiple datasets, those figures include white spikes for nearby cell towers (alternately showing up in red as they are selected), small red triangles for Wi-Fi routers, and similarly sized white and blue squares for satellites (see figure 3 below). As the user pans her cell phone or tablet around, pivoting around her axis, the picture shifts, and the names and distances of different relay devices and access points are provided. Whether the device is held still or moved around, the views it produces always also feature pulsating ‘showers’ of signals, easily perceived as actual data ‘flying about.’ They appear as dots and triangles that shift color and traverse the picture left to right and right to left, but also between foreground and background, thus creating an impression of depth. [13] At times, they assemble as geometric shapes composed of parallel lines, reminiscent of contour lines on topographic maps but roaming around in space.

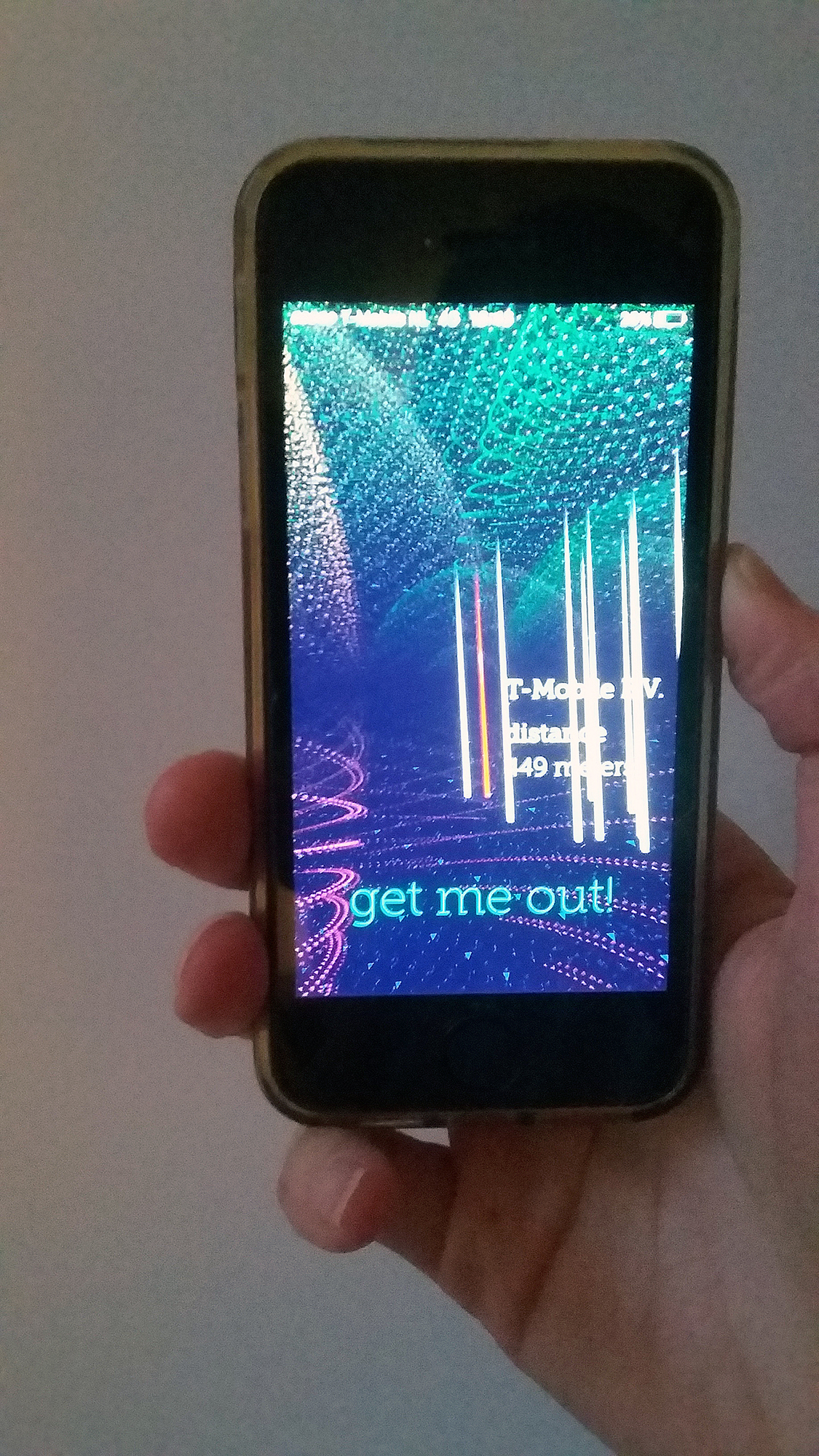

‘Data,’ in Architecture and White Spots, are represented metonymically, because the network scanner only shows material infrastructures and digital radio signals. But the apps also hypothesize on how data circulate in the spaces we inhabit. They suggest that like radio signals, such ‘particles’ flow in waves. They also convey that data move fast and rather frantically – and as a result, an immersed user operating either of the apps in an area with heavy coverage will likely experience them as overwhelming. This is relevant in particular to White Spots, whose network scanner, while visualizing only one type of network (the cellular kind), places nodes and signals or streams more to foreground of the picture than its older sibling.

In discussing his work, Vijgen has repeatedly stated his goal of making the invisible visible. “Unlike the infrastructure of the industrial age, with its railroads, factories and highways,” he writes,

the infrastructure of the digital age is mostly unseeable. Our most tactile interactions with this planetary system are through the touch screens of our devices – an experience set to disappear as connected homes, augmented reality spectacles, and voice controlled assistants render these conventional interfaces more and more redundant. […] While this might be good news in terms of accessibility, it also makes it very difficult to assess what you might be seeing and interacting with. This technological layer, with all of its properties, designed intentions, ideologies, and limitations is still there – it’s just that you can’t see it. […] In my work I use visualisation to probe, explore, and question the role of abstract and invisible technology in modern digital life. [14]

In light of Vijgen’s intent, it is significant that the network scanner view is often characterized as a ‘visualization,’ and more specifically, a ‘data visualization.’ [15] Some image elements are indeed based on actual ‘data’; for instance, information about the locations of relay devices and access points for wireless communication, as well as their distance from the viewer. Others however are conceived in the manner of a simulation, such as the data signals emitted by cell towers or Wi-Fi routers. For this reason, the network scanner also challenges common definitions of data visualization. [16]Yet in spite of this, all components of the piece do serve to visualize, or literally ‘make visible to the eye,’ hidden infrastructures, data and their movements – even if their combination admits to a certain indeterminacy about what exactly is revealed in the process. [17]

In its concern with issues of infrastructural invisibility, Vijgen’s work ties in with current interests in new media and digital culture studies. [18] But arguably, it also aligns with a broader set of developments in contemporary media art practice. As digital art critic Maxence Grugier points out, visualizing what ordinarily remains covert is actually a shared feature, perhaps even a key objective, of all data art. [19] Specific works however confront us with data in different ways; moreover, those that expressly deal with data ubiquity present highly diverse views on how data are ‘present,’ or circulate, in our physical or lived spaces. And while such works often allude in one way or another to the interconnectedness between data saturation and urbanity, they do not engage with it to the same extent, or in the same ways.

As we mentioned, the apps under scrutiny here invoke common associations between connectivity and urbanity. White Spots, which also appeals to one’s desire to escape, thereby positions data ubiquity and (constant) connectedness as urban ‘problems’ or ‘threats.’ In its understanding of those conditions, it ties in with widespread unease about the ways in which digital media and the internet persistently demand our attention, and the social and psychological pressures this imposes – the sorts of concern, indeed, that have recently incited calls for unplugging and mindfulness. [20] As Evgeny Morozov has pointed out, those are reminiscent in turn of early twentieth century anxieties, formulated among others by Georg Simmel and Siegfried Kracauer, about the relation between information overload and disorientation and distraction among city dwellers. Interestingly, the solutions proposed back then no longer suffice today, as withdrawal in the seclusion of the home (as Kracauer suggested) no longer affords the sort of “radical boredom” people are supposedly in need of. [21]

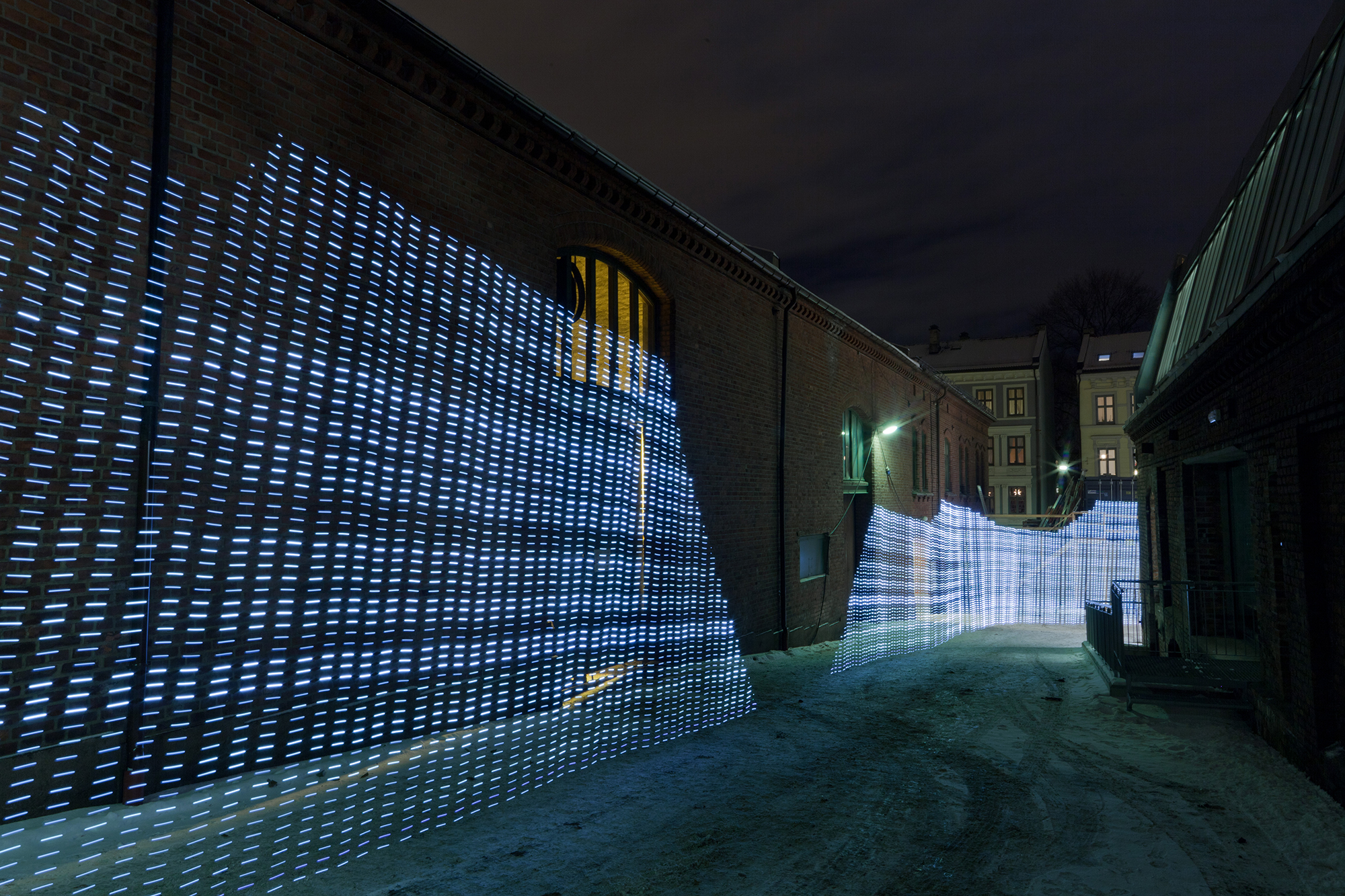

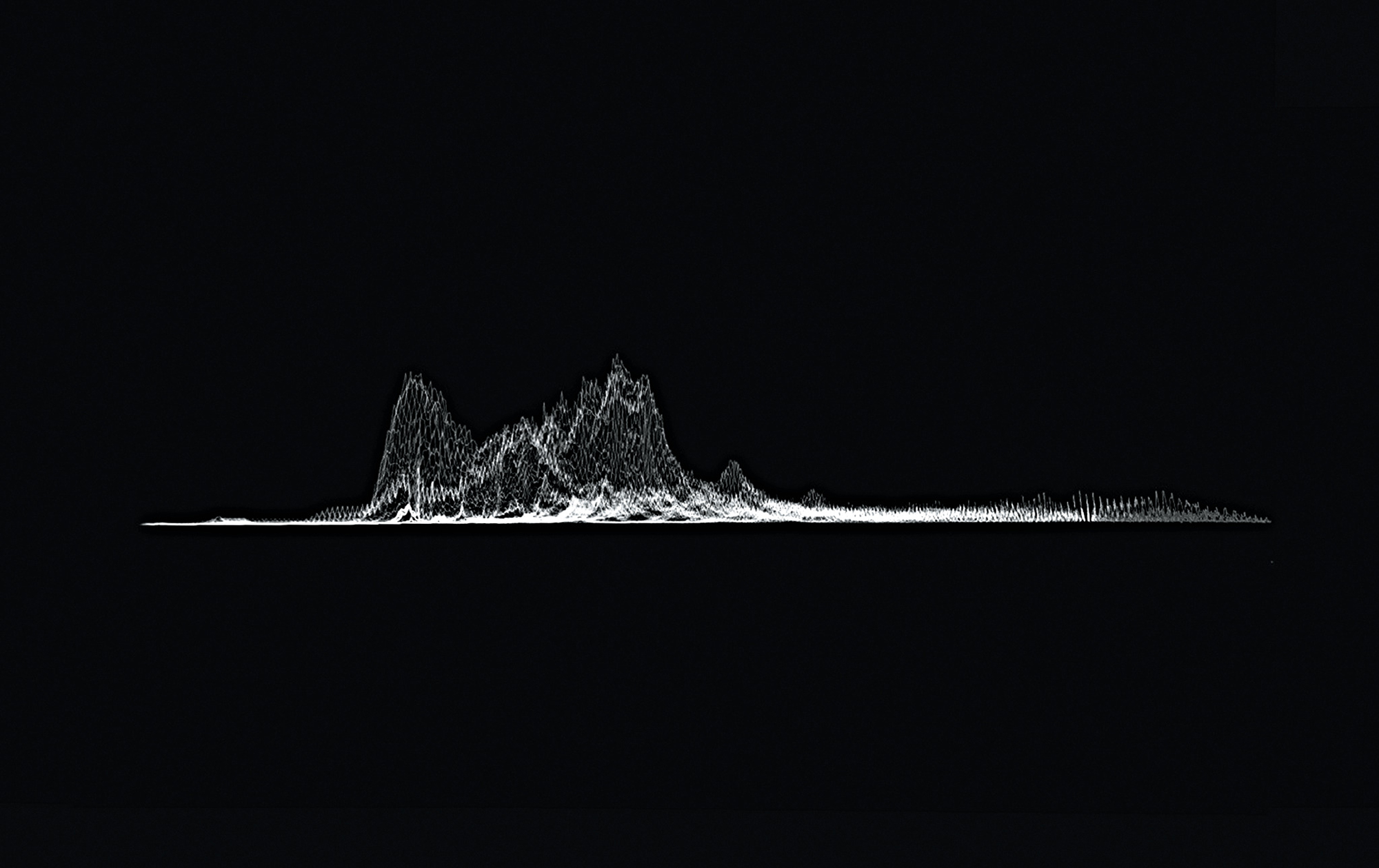

Another artwork that focuses on data ubiquity in the city is Immaterials: Light painting WiFi (Timo Arnall, Jørn Knutsen and Einar Sneve Martinussen, 2011). [22] Unlike Architecture and White Spots, it establishes a direct connection between wireless signals and specific urban sites. The piece is a compilation of long-exposure photographs of ‘light-painted’ Wi-Fi signal strength measurements, visualized as vertical bars of light overlaying the exact spots where they were taken, thus highlighting the signals’ connection, and relevance, to very specific locations (see figure 4 below). The network scanner, by contrast, only gives an approximate idea of where signals originate. But there are other works that underplay this relation even more; for instance, the piece Wifi Spotting (Justin Blinder, 2013), another series of static visualizations concerned with wireless signal strength. [23] Most of the images here focus on the signals that emanate from hotspots; however, the city that underlies them, and the specific sites the signals emerge from, are kept out of sight (figure 5). [24] Unlike the network scanner, this work also gives the data signals or ‘waves’ a vertical orientation, suggesting that data largely circulate above the city and detracting from how they affect city life on the ground.

Another distinction with Vijgen’s work is that those two projects are conceived as flat, static images, that the viewer can only look at (and not manipulate). Moreover, they do not require the observer to be physically present in the urban spaces they represent. In fact, they differ profoundly in terms of how they mediate their users’ encounters with the data-saturated city, and what sorts of encounters they enable. These are the topics we want to turn to next.

Interfaces as Zones of Mediation and Sites of Encounter

As apps developed exclusively for touch-screen devices, Architecture and White Spots call attention to their own status as ‘interfaces.’ In doing so, they foreground the conventional, dictionary meaning of the term, as some kind of a ‘surface’: an area one can manipulate, either in order to gain access to, exchange or transmit something, or to operate something. However, in contemporary media scholarship, there is a certain measure of consensus that it is less productive to conceive of the interface as a ‘thing’ than as a ‘zone’ or ‘site.’ And more precisely, as a zone or site where some form of mediation takes place. [25]

Key authors – Alexander Galloway, Branden Hookway – also reject understandings of the interface as a mere ‘window’ or ‘doorway’: metaphors that erroneously invoke associations with transparency, in the sense of both a lack of mediation and a lack of resistance. Interfaces, they stress, are spheres where something happens or takes shape. Yet in order for this to be possible, a certain measure of “agitation or generative friction” is needed between the different entities or formats that interact. [26] Therefore, the interface is best understood as a kind of ‘threshold,’ or as some argue, a ‘boundary’: a zone that needs to be “worked through toward some specific end” rather than effortlessly crossed or passed by. [27] Hookway, who takes particular interest in the relational aspect of the interface, also characterizes it as a site of ‘encounter’ between different entities. For him, this encounter is very much pre-given, or constituted prior to the encounter taking place. [28] We would argue that this similarly applies to the friction it involves.

Moreover, interfacing always happens at different ‘levels,’ simultaneously. For the user, the most conspicuous level of interfacing is that of her own encounter with the technology or machine, whose ‘language’ she cannot readily understand without some form of ‘translation.’ This understanding is central to the well-known work of Steven Johnson (an early contribution to interface theory), but also to Hookway’s more recent publication on the topic. [29] Galloway however points out that the term ‘interface’ is equally used to denote “the point of transition between different mediatic layers within any nested system,” an understanding derivative of computer science. [30] As Mattern explains, “computer systems are commonly modelled as a ‘stack’ of protocols of varying degrees of concreteness or abstraction”; interfaces, in turn, appear “at every layer of this stack,” mediating between the various protocols. [31]

Our cases suggest that it may be fruitful to extend this ‘levels’ logic of interfacing beyond the technological, interpreting it also more metaphorically. As the interface mediates between a user and a technology, it also establishes a relation, or sets up an encounter, between that user and the particular reality she seeks access to, or seeks to manipulate. Such as, in Architecture and White Spots, our imperceptibly data-saturated habitat, rendered visible. But at the same time, both works, as interfaces, also establish relations between different ‘layers’ of a (hybrid) reality. And last but not least, they engender an encounter between said reality and others, constructing them in the process as distinct ‘worlds.’ As we examine how interfacing in both apps takes place, we are interested also in these different metaphorical levels – and the wider range of entities thus interfaced.

In what follows, we discuss how interfacing takes place at each of the levels mentioned. In doing so, we focus on how the interface mediates, first, between user and machine; next, between different layers of the urban/informational landscape; and finally, between the data-saturated, urban world and its alternatives. In the process, we zoom in each time on the particular app and/or feature where this logic is the most obvious. In our view, it is important to consider what happens at each level, as this helps to reveal how different types of encounters with data in urban space may simultaneously take shape, even within the context of a single work.

Interfacing Urban Data in The Architecture of Radio and White Spots

The Network Scanner: Mediation as Separation

In talking about his work, Vijgen has expressed ambivalence about the need for interfaces in general. The maker deplores that such tools are increasingly ‘inconspicuous,’ or in other words: that interfaces these days somehow seem to obliterate themselves. This tendency, he argues, results in a condition whereby “our window on the digital world is beginning to feel more like a new, auxiliary sense and less like a piece of equipment.” [32] Incidentally, this is also the reason why he tries to make visible the infrastructures that support our interactions with said world. But in realizing this intent, he paradoxically opts for what he personally calls a highly “transparent” design: one that emphasizes “what’s behind the screen rather than what’s on the screen itself.” [33] He supports this choice by arguing that Architecture, instead of dealing with “the content,” focuses on “the system that carries the content.” [34] The result is an app that invites the user to look ‘through’ the screen – at the nuts and bolts that operate the system it relies on for input – rather than ‘at’ it.

Vijgen’s decision, if taken at face value, might suggest that he simply succumbed to the lure of an ‘interfaceless’ interface – the very kind he also debunks as a problematic illusion. [35] But in handling the app, the user notes that it never really achieves the sort of transparency his characterization promises. One reason is that the network scanner raises expectations it does not subsequently meet. In reviews, Architecture is often described as an ‘augmented reality’ (AR) app – and in fact the user, upon installing it, may initially also understand it as such. [36]However, ‘AR’ does not unequivocally capture the network scanner’s relation to the lived environment. Lev Manovich defines the concept as a “laying of dynamic and context-specific information over the visual field of a user,” but without blocking it. [37] In this context, ‘augmenting’ means ‘adding’ to the user’s (visual, but also embodied) experience of a space, without taking it over – thus allowing her to remain in touch with, and consciously ‘present’ in, her corporeal environment. The network scanner’s interface, due to its reliance on a similar layering logic (the visualization, indeed, is dynamic information laid on top of the ‘real world’) along with the 360-degree viewing it imposes, does mimic conventions for AR in hand-held devices. But in doing so, it renders an invisible layer of reality visible rather than to add one. And in visualizing a virtual one, it also ‘covers up’ the material one.

As a result, the app’s user becomes highly conscious of the presence of an interface – whether it is understood in the more conventional, concrete sense of a ‘mediating surface’ (made material by the touch screen of one’s tablet or phone) or in the more abstract sense of a ‘zone of interaction’ between two entities. [38] So, in enabling a visual experience, the network scanner interface also raises a distinct ‘hurdle,’ evocative of a boundary or threshold: something that brings discrete entities together, but in the process somehow also holds them apart. [39] In the network scanner, this holding apart or separating is almost palpable, primarily because of the app’s lack of transparency. Arguably, this effect is reinforced by the circumstance that the user handling the device – an act that in itself detracts from the immersiveness of the experience – needs to exert a good deal of mental effort to actually get absorbed in the image it generates. To get properly immersed in a “world of wireless digital signals,” she has to actively ignore her actual environment. [40] This is remarkable, as the network scanner’s visualization only makes sense in relation to this physical space – a space which, therefore, the user at the same time needs to imaginatively invoke.

The Architecture of Radio and White Spots: Privileging an Invisible Layer of the City

In both apps, then, the interface’s simultaneous connecting and separating of entities is clearly at work at the level of the encounter between the user and the technology, and by extension, between the user and that which Vijgen situates ‘behind’ the screen. But it is also significant at the level where the different layers of the city meet each other, or intersect: the physical, and visible, urban layer, and a more intangible, and ordinarily also invisible, informational layer (with both material and immaterial dimensions).

As the project website for Architecture states, the visualization the apps generate are based on a logic of “reversing the ambient nature of the infosphere; hiding the visible while revealing the invisible technological landscape we interact with.” [41] Both works thus give rise to a very specific relation between the constituents of the hybrid reality they construct. Arguably, this results in the network scanner squarely privileging the informational layer or dimension of this reality – to the detriment of the city as a spatial entity.

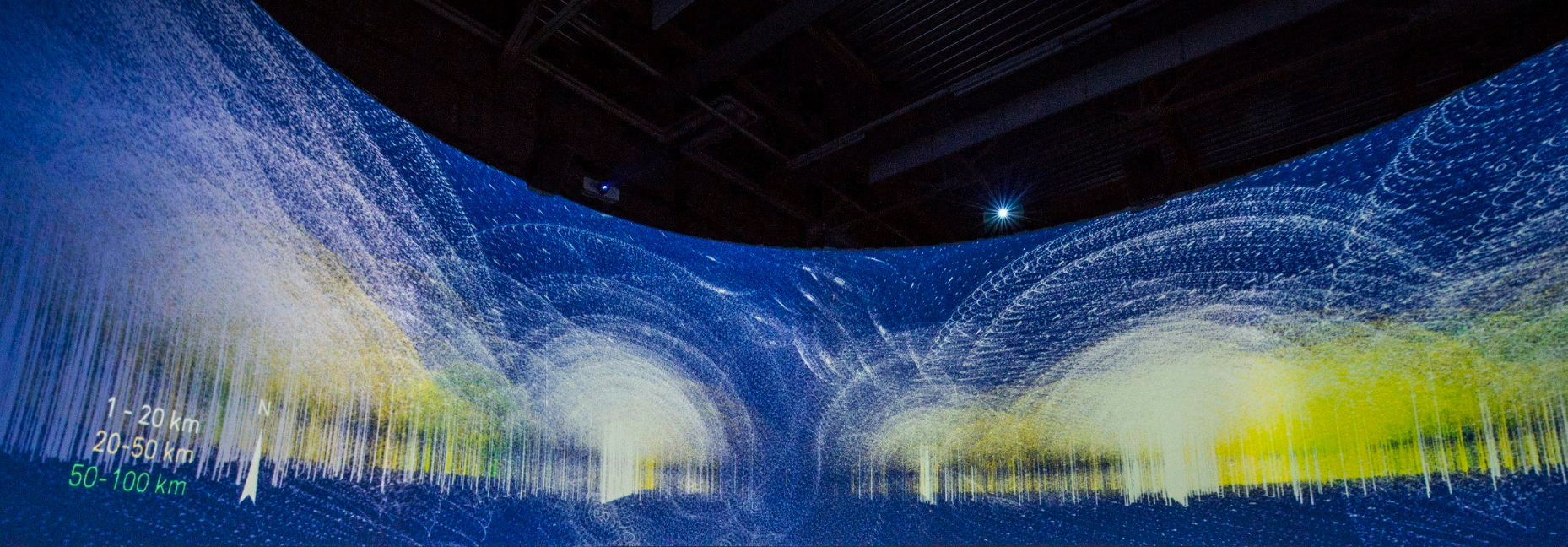

In the world that comes about through the apps’ use, the presence of a physical city is certainly intimated. But this city is only meaningful as the site of a series of data inputs – the same inputs that also serve as indexical traces in the reconstruction of this site that the network scanner presents. [39] So, while the material city is not rendered irrelevant, it is only significant in terms of how it anchors the informational; that is, how information originates in specific material places. In the network scanner view, those places are shown as approximate locations, relative to the viewer’s position – but without any visual reference to their physical surroundings. (Which, indeed, is why it requires an act of the imagination to truly ‘visualize’ the relation between the city’s layers.) Remarkably, this situation also applies to Architecture’s more immersive incarnations, such as the VR version (for iPhones equipped with a cardboard or compatible headset) and a range of site-specific variants, including the 360-degree projection/installation pictured below (see figure 6). [43]

Considered from this perspective, the different versions of the app contrast with at least one of the other works we previously mentioned. The photographic compilation Immaterials, making use of an actual overlay logic (as opposed to a mere overlay ‘aesthetic,’ as in the network scanner’s case), never allows the light-painted signals to block the city from view. By merging the layers of the hybrid city rather than to privilege one over the other, it gives expression to an imagination of the relation between data and physical space as much more entwined. But this comparison also serves to underscore the extent to which each interface pre-constitutes, as Hookway puts it, the encounter between user and city. [44] Especially the immersive versions of Architecture, unlike Immaterials, thrust the informational dimension of this environment quite forcefully onto the foreground, thereby shaping the entire interactive experience.

Another determining factor in the privileging of the invisible data layer of the city in both apps is the use of sound. Mattern, who elaborates on Galloways’s definition of the interface as “a general technique of mediation evident at all levels [of a computer’s ‘stacks’],” specifies that this technique can be graphical, but also gestural for instance, or sonic. [45] The fundamental role of sound in conveying information is increasingly being recognized, especially in the context of information design; in interface analysis, in contrast, it is all-too-often still ignored. [46] Such oversight also manifests in reviews and online discussion about the apps.

In both network scanners, views of the infosphere are supplemented with a prominent soundscape. The images of data infrastructures and streams are accompanied by a low rumbling, combined with ticking and crackling sounds and static noises that change quality as the device is panned (and in relation to the types of transmitters in view and a user’s distance from them). More occasionally, a stronger synthetic sound is also audible, vaguely reminiscent of those adopted by early computer games. Vijgen has indicated that his sound design was loosely based on noises picked up while listening to a software-defined radio (SDR): a receiver that allows one to tune into signals from cell towers, satellites, and so on. So, much like in the visual domain, the impulse here was to make something heard that ordinarily cannot be perceived – even if ultimately, the result is a simulation. [47] The noises featured have a pulsating quality, inducing a kind of restlessness in the hearer similar to that caused by the visuals. The static sounds in particular actually convey a sense of data flows somehow ‘interfering’ (although it remains undetermined what with).

In an outdoor setting, the fabricated sounds may blend with the everyday noise of the city. Yet in spite of this, they still acquire what cinema scholar Michel Chion, in the early 1990s, termed ‘added value’: “the expressive and informative value with which a sound enriches a given image” and that further highlights the information contained in it. [48] In Architecture, the quality and intensity of the noises change as the user adjusts her position and other data points and streams come into view, which serves to mimic the differences in quality and intensity suggested by the visuals. In White Spots, where the swaths of geometrical figures that represent the data streams charge at the viewer at higher velocity, the sound is more monotonous, and the static more constant. Here, noise forms part of a larger ensemble of crushing sensory stimuli that together underscore the oppressiveness of omnipresent data, and thereby plants in the viewer a stronger sense of urgency to escape. In both cases, sound thus contributes to the privileging of the data layer of the city; in White Spots, however, there is a more obvious analogy to be drawn with the (aural and visual) cacophony of a busy urban environment, that may also incite withdrawal.

White Spots: Shaping Subject and Agency in the Encounter between Distinct Worlds

As we mentioned, the White Spotsapp quite literally pitches the possibility of escape to the user. As figure 7 shows, the network scanner here not only displays the familiar spikes (representing cell towers) and dense clouds of triangles (data), but also, at the bottom, a command button with the text “get me out!” By tapping it, the user enters a map feature that visualizes the global divide between connected areas (showing up as dark) and disconnected ones (quite literally ‘white spots’). Here, she can also browse photo reports and short documentary videos, among others about life ‘off the grid’: in locations not covered by the signals and data streams that the network scanner renders visible. [49] By subsequently clicking a “take me there!” button, she finally ends up in the route planner function of her device, which allows her to plot her way to a nearby ‘off’ zone.

The transition from an interface based on some kind of a layering logic (albeit not strictly speaking AR) to a map mode is significant not only in terms of the use and perspective the app affords, but also in terms of how it mediates between what we previously called distinct ‘worlds.’ It is at this point, then, that we arrive at the third (metaphorical) ‘level’ of interfacing identified above. In what follows, we briefly address White Spots’functional affordances; subsequently, we expand on how exactly the app’s interface constitutes the distinction, perhaps even opposition, between said worlds. In doing so, we are interested in how exactly it is ‘productive’ – not only of this distinction, but also of a specific form of agency, and a given subject position, on the user’s part.

A key functional difference between the scanner and map features is that while the former requires an upright device (turned around to produce a 360-degree picture), the latter does not. [50] As the user enters the map feature, she can also hold her device horizontally, in the manner of a city plan or atlas. This entails that she switches to a different sort of vantage point. No longer placed at the center of the image, and seeing only one piece of the surrounding landscape at a time, she is turned into a distant observer, surveying a large terrain from afar and above (see figure 8). Confronted, first, with a view of about a quarter of the globe, she is subsequently invited to zoom in. Yet even if she does, she continues to hover over a two-dimensional landscape rather than to get immersed in a three-dimensional one.

The transition from scanner to map mode also makes for a different shift, that highlights another spatial dimension to the interfacing taking place. Considered in isolation, the network scanner mediates between visible (physical, urban) and covert (virtual, informational) dimensions of an essentially hybrid reality. A reality, indeed, that converges ‘right here’: in the location that the user is at the center of. But in the move from layering to map logic, the app also interfaces between different realities, constituted in the process as different ‘worlds.’ In this transition, White Spotsmediates between the urban, data-saturated, and by extension, hyper-connected world that the user is currently part of, and its alternative, which she can navigate to: those areas, presumably non-urban, that together constitute an off-line, disconnected world. Arguably, it is here that the user is made most acutely aware of the interface’s fundamental productiveness.

First, because at this level, the app is the most clearly ‘actionable.’ Hookway, we mentioned, sees the interface as constitutive of a particular relation between human and machine – a relation, indeed, that is essentially pre-given. This pre-givenness is relevant also in terms of the agency, or “the will and means to action,” that the interface affords the user. [51] Human agency, the author argues, “is a capacity at once mediated by and produced upon the interface.” [52] By imposing itself as a necessary condition, such an interface actually “comes to define human agency,” in that it plants in the user an obligation to respond in a specific way. [53] However, the comparison between Architecture and White Spots shows that the types of action thus afforded are quite diverse – as are the means by which this is done.

Vijgen, in explaining Architecture’s rationale, explicitly positions it as a facilitator of agency. He suggests that it is designed primarily as a tool for creating awareness; by visualizing the infosphere, he claims, the app invites the user to consider “the role of abstract and invisible technology in modern digital life.” But he also implies that in doing so, it enables her to partake of this life in a more “active” way. [54] One should note however that neither the awareness thus created nor the potentially ensuing behavioral changes can be seen as an agency (in Hookway’s sense) that the interface is immediately productive of. Ultimately, all the interface does is to shape an experience – more or less immersive, depending also on the user’s contribution, but certainly affective – of an overwhelming ‘parallel’ reality. But a reality that she cannot directly interfere with. And if the user does gain specific insights in the process (for example, based on scrutiny of the available numerical data) she may indeed choose to act upon them. But arguably, not until after the app is lain aside. In other words: the capacity for action thus created is no longer, to reiterate Hookway’s formulation, “at once mediated and produced upon [an] interface.” [55]

In White Spots, where the network scanner feature is combined with other features and also framed by them, the situation is quite different. Here, Vijgen has pointed out, scanning the infosphere is merely an “intermediate step” towards something else. [56] If Architecture is designed to invite users to study ‘the system’ and ideally become more aware of its crucial agency, White Spots, which also appeals to their desire for disconnection, offers them if not an actual opportunity, then at least the prospect of quite literally ‘getting out.’ As in the case of Architecture, users cannot directly interfere with the reality visualized. But the app’s map features do allow them to imagine how to evade it, by withdrawing into a world where said system no longer wields influence. In the move from scanner to map, then, the app turns into what Per Mollerup has called a ‘wayshowing’ device: one that assists the user – if willing – to find her way someplace else. [57] In the process, it also turns into an actual ‘tool’: a mobile (pocket-size) device that enables the performance of a pre-set task (to plan for escape). How exactly this task is performed depends in part on the user’s preferences, as she can navigate far and wide. In this respect, then, White Spots’interface, while obviously productive of a very specific sort of ‘act,’ is simultaneously less restrictive in its actionability than Architecture.

A second aspect of the app’s operation that foregrounds the interface’s fundamental productiveness is its molding of the user into a specific subject position. Both Hookway and Mattern emphasize the role of the interface in ‘subjectifying’ the user. In structuring, or as Hookway puts it, ‘defining’ her agency, the interface also constructs her as a ‘subject’ whose identity shifts “in response to contextual variations.” [58] Mattern’s work is particularly productive here, as it focuses on how this affects the user, very specifically, in her identity as an urban subject. In a piece on urban dashboards, the author argues that such devices “do not merely define the roles of the user […,] they also construct her as an urban subject and define, in part, how she conceives of, relates to, and inhabits her city.” By extension, “the system also embodies a kind of ontology: it defines what the city is and isn’t, by choosing how to represent its parts.” [59]

As we explained, Architecture and White Spots characterize urban space as inundated by data signals; the latter work thereby also pictures the city dweller’s condition as one of enforced connectedness. Yet in doing so, White Spots inevitably attests to a very partial understanding of what it means to be ‘connected.’ On the one hand, this understanding is highly technological or ‘infrastructural’ in nature, as the chief measure of connectedness is the mere presence of wireless data signals. By implication, the app does not visualize alternative forms of (dis)connectedness. For example, it does not show what we might call ‘social’ white spots, or as Sherry Turkle puts it, “sacred spaces”: places where there is coverage, but where people are either asked to stay off-line or deliberately choose to do so. [60] While this possibility is alluded to in one of the films the app features, its various visualizations do not invite such an interpretation. [61] On the other hand, connectedness is also understood as something experiential. It is pictured as causing a sense of oppression; so as an experience, it is quite problematic – much like some people’s perceptions of city life itself. The app’s user is maneuvered into the subject position of a city dweller who seeks to protect herself from the risk of mental exhaustion, resulting from the sensory overstimulation that is so peculiarly urban – but in its present-day version, causally related to the presence of wireless technology. Much like the experience itself, the responsibility for averting said risk is portrayed as entirely personal (rather than collective or communal). [62]

However, the problems associated with connectedness, and by extension, city life as such, do not imply that either of those conditions is entirely undesirable. The prospect of escaping to an off-line world, after all, is attractive precisely because it is a luxury, afforded to those who are fortunate enough to lead a comfortable – and well-connected – metropolitan life. [63] Once again, the subject position imposed on the app’s user is highly revealing here.

If Architecture is characterized by its tag line as “A field guide to the hidden world of digital networks,” White Spots more obviously complies with the logic of exploration that informs this genre. Both in the app and in all manner of paratexts, the practice of seeking out cellular blind spots is presented as an adventure. The user, as she enters the route planner, is greeted with the words “Hi Explorer!” Moreover, areas with lack of connection are referred to as “uncharted territory,” and in interviews and presentations, Vijgen has characterized those areas as a twenty-first-century kind of “terra incognita.” [64] A pop-up message even forewarns the user of the possibility that going on an “expedition” in search of white spots might result in the loss of cell phone signal, and therefore, the inability of using the device “to find [one’s] way home.” This suggests that such an undertaking is at the very least exciting, perhaps even a little dangerous. Arguably, elements like these contribute to what Mattern sees as a colonialist attitude apparent in contemporary forms of the field guide. [65] White Spots expresses this stance through its unspoken assumption that the user, while ‘belonging’ in a modern, urbanized environment, might crave temporary refuge in a world where life is less overwhelming: simpler, but by implication, somehow also less ‘advanced.’ Significantly, those regions are mostly located in the global South and East, where apart from coastal areas, the map shows a wiry maze rather than solid black (as it does in the North and West).

White Spots, then, not only creates an opposition between urban and non-urban areas, but also stages an encounter between technologically, and by extension socio-economically, ‘developed’ and ‘developing’ parts of the globe. In so doing, it portrays connectivity as a distinctly ‘First World’ condition. Politically speaking, its attitude in the matter is rather ambiguous. On the one hand, the map function exposes unequal access to (specifically cellular) connectivity, thus casting the ‘digital divide’ as a problem. [66] But on the other, it invites the user to ‘discover’ unexplored, digitally speaking ‘pristine’ parts of the world – appealing in the process to her sense of Western superiority. This also happens in some of the films that zoom in on the experience of the people who actually live in those areas. While those videos do undermine the notion that said regions are indeed unexplored, they tend to highlight the locals’ resourcefulness in what are essentially adversarial (because ‘backward’) conditions. Once again, it is relevant here that the map and route planner favor a representation of the world from above – a technique which, Helen Kennedy at al. argue, can easily “be used in the interests of the privileged and powerful.” In addition, the map mode also lacks perspective, and, as the same authors point out, this conveys an impression of objectiveness. Arguably, both these factors serve to further obfuscate what Mattern calls the field guide’s “necessary partiality.” [67]

In its contribution to a given portrayal of reality, the interface introduces or reinforces certain needs in its user; at the same time, it also gives rise to, or perpetuates, a given set of subjectivities. White Spots in particular marks those subjectivities as specifically ‘urban.’ But in doing so, it attests to a highly selective understanding of what sets the city apart. For instance, given that a place’s connectivity status is determined to a considerable extent by socio-economic conditions, the app is actually very likely to detect enough signals for a ‘data shower’ (small or large, less or more intense) anywhere in the inhabited North-West – not just large cities, but also smaller towns or (populated) villages. In doing so, it basically ignores or devalues other, commonly agreed-upon markers of urbanity (such as, in the above example, even just the size of a given settlement). And in the process, it overthrows existing ontologies of the urban (as Mattern called them). Clearly, the ontologies that substitute for them need to be critiqued, as they give expression to the cultural values, or social norms, that are embedded in interfaces and reinforced through design. [68]

Conclusion

In our attempt to diversify between the ways in which the two apps under scrutiny enable, and in the process shape, interactions with a data-saturated, urban environment, we have proposed to conceptualize interfacing as something that happens, simultaneously, at three distinct (metaphorical) ‘levels.’ This has allowed us to tease out the differences in mediation as it takes place between a user and technology, and by extension also the particular reality it provides access to; between the different layers of this reality; and finally, between this reality and others (the latter realities that may even be conceived of as distinct ‘worlds’). This has helped us to systematically identify the different ways in which interfaces give shape to a variety of relations between users, technologies, and physical and virtual realities. But arguably, it has also broadened our perspective on which entities exactly such tools interface, or mediate, between.

Ultimately, our explorations converged around questions concerning the interface’s productiveness. Such questions, indeed, are relevant at all the levels of mediation discussed. In the encounter between user and technology, interfaces shape experiences of the worlds they give access to, which entails that those are perceived as distant or close, revealed or covered up, intangible or highly manipulable, and so on. But in the process, they also work to privilege or disadvantage certain dimensions of an actual (experiential) reality. As Mattern points out, it is important to consider this, as we tend to “forget just how extensively […] layered interfaces structure our communication and sociality, how they delimit our agency,” and importantly, “how they are defining the terrain we’re interfacing with.” [69] In the case of urban interfaces specifically, this begs the question what exactly the city is that they put users in relation with. [70] In shaping understandings of the city, interfaces may challenge, or critique, conditions that are taken for granted. But sometimes, our cases show, they also reaffirm them – and sometimes even simultaneously (albeit perhaps in more subtle ways).

What our analyses ultimately suggest is that the interface gives expression to social as well as technical imaginaries. In Architecture and White Spots, the technological most definitely takes center stage, as both works directly engage with the nature, or structure, of data networks. But at the same time, they are revealing, and constitutive, of the ways in which we imagine our collective social lives. [71] White Spots, we argued, expresses profound ambivalence towards our contemporary condition of connectedness. In addition, it relies on an essentially binary logic: one is either connected, or one is not. In this scenario, connectedness means ‘being within wireless reach’ – a condition associated in turn with a specific location or place – but by implication also ‘active online.’ (And for this reason, indeed, unplugging, in the twenty-first century, requires the radical solution of leaving the city, or even the inhabited world – unlike what Kracauer proposed.) This is remarkable, since alternatives to this conception are also imaginable, and the two conditions (being within reach and being active online) need not overlap.

The mere fact that White Spots’ interface privileges such a reading entails that it requires critical scrutiny not only of how it imagines our technological environment, but also of the ways in which we interact with them socially – or of how the app claims we should. Confrontation of both works with other examples will likely prove productive here: not only in exploring further distinctions between interfaces in terms of their productiveness, but also for the purpose of appraising the different (techno-)social imaginaries they suggest.

Acknowledgments

Our thanks go to the issue editors and the anonymous peer reviewer, for their comments on earlier versions of this text, and to Richard Vijgen, for his generous cooperation in this research.

Authors’ Biographies

Eef Masson is an assistant professor of Media Studies at the University of Amsterdam, where she teaches courses in film and media history and media archiving and preservation. She has published on non-fiction and non-theatrical film (among others, her book Watch and Learn: Rhetorical Devices in Classroom Films after 1940, Amsterdam University Press 2012), media archives, museum media, and more recently, data visualization – specifically in artistic practice and media (history) research. Currently, she acts as senior researcher in the project The Sensory Moving Image Archive: Boosting Creative Reuse for Artistic Practice and Research, which examines the affordance of visual analysis and visualization tools for the exploration and repurposing of digitized moving image collections.

Karin van Es is an assistant professor of Media and Culture Studies at Utrecht University, and coordinator of the Datafied Society research platform. Her publications to date among others deal with liveness, specifically in television, social media, and social TV. Examples are her book The Future of Live(Polity 2017) and articles in Television & New Media, and Media, Culture & Society. Recently, she has been focusing increasingly on datafication and its study, and data analysis and visualization; among others, as co-editor of, and contributor to, the volume The Datafied Society: Studying Culture through Data (Amsterdam University Press 2017, with Mirko Tobias Schäfer). Her current research is concerned with public service television and public values in the digital age.

Notes and References

[1] Shannon Mattern, Code and Clay, Data and Dirt: Five Thousand Years of Urban Media (Minneapolis, MN: University of Minnesota Press, 2017).

[2] Mattern, Code and Clay, Data and Dirt, 1-2.

[3] Richard Vijgen, The Architecture of Radio, iPad app, 2015. The app is available for iOS and Android devices.

[4] Architecture of Radio, “Architecture of Radio: A Field Guide to the Hidden World of Digital Networks, ”project website, accessed September 28, 2018, http://www.architectureofradio.com/. At the time of finalizing this article, this website featured a short demo, which the reader might consult for better comprehension of the app’s operation. The datasets used are derived, respectively, from OpenCellID (a collaborative community database that contains GPS positions of cell towers, created primarily to serve as a data source for GSM localization), Caltech’s Jet Propulsion Lab (whose key activity is building unmanned spacecraft for NASA) and mylnikov.org’s Wi-Fi database (an API that enables users to fetch geo-location information on the basis of Wi-Fi positions). See Richard Vijgen, “Life in the Infosphere,” Total Space supplement to the Volume journal, no. 50 (January 2017): 27.

[5] We previously discussed this case in Eef Masson and Karin van Es, “Visualizing Connectivity: Data as Evidence in The Architecture of Radio,” First Monday 22, no. 10 (October 2017), https://doi.org/10.5210/fm.v22i10.8039.

[6] Richard Vijgen, Bregtje van der Haak and Jacqueline Hassink, White Spots, iPhone app, 2016.

[7] White Spots, “White Spots: A Journey to the Edge of the Internet,” project website, accessed September 28, 2018, http://white-spots.net/. Again, this site features a short demo of the app. The project also includes a television broadcast (for the Dutch broadcaster VPRO), a documentary film, a book, and a travelling exhibit.

[8] Mats Eriksson and Jaap van de Beek, “Is Anyone Out There? 5G, Rural Coverage and the Next 1 Billion,” IEEE CTN, November, 2015, http://www.comsoc.org/ctn/anyone-out-there-5g-rural-coverage-and-next-1-billion.

[9] Mattern, Code and Clay, Data and Dirt, vii-viii.

[10] This is evident also from the short videos of global ‘white spots’ which users can play back, and which situate their stories in remote areas unaffected by the various physical and mental discomforts so characteristic of a busy urban life.

[11] Branden Hookway, Interface (Cambridge, MA: MIT Press, 2014), 1, 4 (for a discussion of the interface as a relation); ibid., 12 (where the interface is positioned as a zone of encounter).

[12] The term ‘betweenness’ as used here is inspired by Nanna Verhoeff, “Interfacing Urban Media Art,” in What Urban Media Art Can Do: Why, When, Where and How, eds. Susa Pop, Tanya Toft, Nerea Cavillo, and Mark Wright (Stuttgart: avedition, 2016), 191.

[13] Vijgen explains that for the visualization of the signals, he used a ‘super-formula’ that allowed him to create a diversity of complex three-dimensional shapes that have both a certain aesthetic appeal and a likeness to magnetic patterns. Richard Vijgen, email message to Karin van Es, January 8, 2017.

[14] Vijgen, “Life in the Infosphere,” 27.

[15] For instance, on the Architecture of Radio project website, and in the “Architecture of Radio” entries on iTunes Preview, accessed August 22, 2017, https://itunes.apple.com/nl/app/architecture-of-radio/id1035160239?mt=8, and Google Play, accessed August 22, 2017, https://play.google.com/store/apps/details?id=nl.richardvijgen.architectureofradioAndroid&hl=nl. But also, in reviews, such as Michael Kaufman, “Surrounded By ‘Architecture of Radio,’” Geekdad, November 29, 2015, https://geekdad.com/2015/11/architecture-of-radio/, or Kelsey Campbell-Dollaghan, “If Our Eyes Could See Wireless Signals, Here’s How Our World Might Look,” Gizmodo, August 24, 2015, https://gizmodo.com/if-our-eyes-could-see-wireless-signals-heres-what-the-1726215792.

[16] For further elaboration of these points, see Masson and Van Es, “Visualizing Connectivity.” For definitions of data visualization and an inventory key of characteristics, see Lev Manovich, “What is Visualization?” Poetess Archive Journal 2, no. 1 (2010), https://journals.tdl.org/paj/index.php/paj/article/view/19/58.

[17] This is also Shannon Mattern’s assessment in “Cloud and Field: On the Resurgence of ‘Field Guides’ in a Networked Age, ”Places Journal (August 2014), https://doi.org/10.22269/160802.

[18] Such interest dates back to at least 1997, when Steven Johnson expressed unease about living in “a society that is increasingly shaped by events in cyberspace” while “cyberspace remains, for all practical purposes, invisible, outside our perceptual grasp.” Steven Johnson, Interface Culture: How New Technology Transforms the Way We Create and Communicate (New York, NY: Basic Books, 1997), 19. More recently, authors such as Lisa Parks have been trying to find ways to interrogate the invisible infrastructures that enable such events, in order to make them intelligible. This work builds on previous efforts in geography and urban studies, Science and Technology Studies, and environmental- and resource-oriented strands of media studies. See for instance Lisa Parks, “‘Stuff You Can Kick’: Towards a Theory of Media Infrastructures,” in Between Humanities and the Digital, eds. Patrik Svensson and David Theo Goldberg (Cambridge, MA: MIT Press, 2015), 356; and Lisa Parks, “Earth Observation and Signal Territories: Studying U.S. Broadcast Infrastructure Through Historical Network Maps, Google Earth, and Fieldwork,” in New Media, Old Media: A History and Theory Reader, 2nd ed. (New York, NY and Oxon: Routledge, 2016), 92-113. Others have also questioned what it means for data and their infrastructures to be ‘visible,’ suggesting that visibility and intelligibility do not necessarily coincide. See for instance various contributions to Alix Johnson and Mél Hogan, eds. “Location and Dislocation: Global Geographies of Digital Data,” special issue, Imaginations 8, no. 2 (September 2017), http://imaginations.glendon.yorku.ca/?p=9947. See also Mattern, “Cloud and Field,” in which the author demonstrates that ‘making visible’ doesn’t necessarily mean ‘making clear.’

[19] Maxence Grugier, “The Digital Age of Data Art,” TechCrunch, May 8, 2016, https://techcrunch.com/2016/05/08/the-digital-age-of-data-art/.

[20] See for instance Nicholas Carr, The Shallows: What the Internet is Doing to Our Brains(New York, NY: Norton, 2010); Sherry Turkle, Alone Together: Why We Expect More from Technology and Less from Each Other(New York, NY: Basic Books, 2011); and Tim Wu, The Attention Merchants: The Epic Scramble to Get Inside Our Heads (New York, NY: Knopf, 2016).

[21] Evgeny Morozov, “Only Disconnect: Two Cheers for Boredom,” The New Yorker, October 28, 2013, http://www.newyorker.com/magazine/2013/10/28/only-disconnect-2. References for the work he mentions are Georg Simmel, “The Metropolis and Mental Life,” in The Blackwell City Reader, eds. Gary Bridge and Sophie Watson (1903; Oxford and Malden, MA: Wiley-Blackwell, 2002), 11-19; and Siegfried Kracauer, “Boredom,” in The Mass Ornament: Weimar Essays, trans. and ed. Thomas Y. Levin (1924; Cambridge, MA and London: Harvard University Press, 1995), 331-336. We should add here that Morozov sees such concerns return again in the early 1960s, for instance in the work of the French philosopher Henri Lefebvre.

[22] Timo Arnall, Jørn Knutsen, and Einar Sneve Martinussen, “Immaterials: Light painting WiFi,” Vimeo video, 4:50, February 26, 2011,https://vimeo.com/20412632. See also Einar Sneve Martinussen, “Immaterials: Light painting Wifi,” YOUrban, February 22, 2011, http://www.yourban.no/2011/02/22/immaterials-light-painting-wifi/ (accessed August 18, 2017); and Timo Arnall, Jørn Knutsen and Einar Sneve Martinussen, “Immaterials: Light painting Wifi,” Significance 10, no. 4 (August 2013): 38-39, https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1740-9713.2013.00683.x. The work first came to our attention via Mattern, Code and Clay,Data and Dirt, 1.

[23] However, ‘strength’ in this case is understood in terms of the number of Wi-Fi hotspots, rather than the sum total of signal strength, in particular areas of the city. For a selection of images from this series, see Justin Blinder’s personal website, “Wifi Spotting,” accessed August 18, 2017, http://projects.justinblinder.com/Wifi-Spotting.

[24] The relevant page on Blinder’s website also includes some aerial views of Manhattan and its surroundings with the data on hotspot saturation mapped as a 2D Mercator projection; however, it is not clear whether these are part of the actual series. Signal density, in any case, is not as powerfully represented here.

[25] See for instance Alexander R. Galloway, The Interface Effect (Cambridge: Polity Press, 2012), vii (where the author speaks of a ‘zone’); or Hookway, Interface, 12 (where both ‘zone’ and ‘site’ are used). Even Johnson, in the late nineties, already spoke of a ‘zone’ between medium and message (see his Interface Culture,41).

[26] Galloway, The Interface Effect, 31; ibid., 25, 39-40 (for a discussion of the unsuitability of the ‘window’ metaphor); Hookway, Interface, 7 (for more on the need for ‘friction’); and ibid., 1, 12, 14 and passim(where arguments are made about the requirement of activity).

[27] Hookway, Interface, ix. Galloway, in The Interface Effect, implies that he actually prefers ‘boundary’ to ‘threshold,’ because for him, the latter term holds the same connotations as ‘window’ (25). In spite of this, he keeps using it in his book.

[28] Hookway, Interface, 1.

[29] Johnson, Interface Culture; Hookway, Interface.

[30] Galloway, The Interface Effect, 31 (our emphasis).

[31] Shannon Mattern, “Interfacing Urban Intelligence,” in Code and the City, eds. Rob Kitchin and Sung-Yueh Perng (London and New York, NY: Routledge, 2016), 51.

[32] Vijgen, “Life in the Infosphere,” 27. Compare also Galloway, who partly blames reductive understandings of interfaces as ‘windows’ on the way they are commonly designed (The Interface Effect, 53).

[33] Vijgen, “Life in the Infosphere,” 27.

[34] Ibid.

[35] Ibid.

[36] For instance, Michael Kaufman, “Surrounded By ‘Architecture of Radio’” (see the tags at the bottom of the article); Dante D’Orazio, “See the Invisible Wireless Signals Around You with this Augmented Reality App,” The Verge, November 28, 2015, https://www.theverge.com/2015/11/28/9811910/augmented-reality-app-lets-you-see-wireless-signals; David Murphy, “iOS App Visualizes the Wireless Signals That Surround Us,” PCMag.com, August 27, 2015, https://www.pcmag.com/article2/0,2817,2490230,00.asp. The last of these articles adds nuance in that it says it does what it does “in an augmented reality-like fashion.”

[37] Lev Manovich, “The Poetics of Augmented Space,” Visual Communication 5, no. 2 (June 2006): 219-240; quote: 222.

[38] The notion of a ‘mediating surface’ is inspired by Verhoeff, “Interfacing Urban Media Art,” 190-99; ‘zone of interaction’ is used in Galloway, The Interface Effect, vii.

[39] The formulation here is inspired by Hookway, Interface, 4.

[40] Quotes taken from the “Architecture of Radio” entries on iTunes Preview and Google Play; see [15].

[41] Architecture of Radio project website (our emphasis); see [4].

[42] In “Visualizing Connectivity” we elaborate further on how the network scanner’s visualization functions within what Mitchell Whitelaw has called an “indexical paradigm”; see Whitelaw, “Art Against Information: Case Studies in Data Practice,” The Fibreculture Journal, no. 11 (2008), http://eleven.fibreculturejournal.org/fcj-067-art-against-information-case-studies-in-data-practice/.

[43] The VR function is available for versions 0.0.6 of the app and up. The 360-degree projection was premiered at the STRP Biënnale 2017 in Eindhoven, the Netherlands (March 24 to April 2, 2017). The very first site-specific version was exhibited at ZKM Center for Art and Media in Karlsruhe, Germany (September 5, 2015 to January 31, 2016; this was also the first implementation of the app altogether).

[44] Hookway, Interface, 1.

[45] Mattern, “Interfacing Urban Intelligence,” 51.

[46] For evidence of such recognition in the field of interface design, see for instance Ariadna Matamoros Fernandez, “Listen to This: Don’t Miss the Sound to Convey Data!” Masters of Media, April 15, 2014, http://mastersofmedia.hum.uva.nl/blog/2014/04/15/listen-to-this-dont-miss-the-sound-to-convey-data-2/.

[47] Richard Vijgen, email message to Karin van Es, January 8, 2017; Richard Vijgen, Q&A following untitled presentation at the Imagining [Urban] Data Visualization expert meeting (Utrecht University/Parnassos, February 27, 2017).

[48] Michel Chion, Audio-vision: Sound on Screen, trans. Claudia Gorbman (New York, NY: Columbia University Press, 1990), 5.

[49] In the relevant version of the app, a number of VR experiences are also available.

[50] The network scanner feature in White Spots, unlike that in Architecture, even prompts the user to hold her device upright if she does not do so right away. The same prompt does not appear in the map feature.

[51] Hookway, Interface, 1, 5.

[52] Ibid., 17.

[53] Ibid.

[54] Vijgen, “Life in the Infosphere,” 27.

[55] Hookway, Interface, 17.

[56] Richard Vijgen, email message to Karin van Es, January 8, 2017.

[57] Per Mollerup, Wayshowing > Wayfinding: Basic & Interactive (Amsterdam: BIS Publishers, 2013). One of us has made this point earlier, in Nanna Verhoeff and Karin van Es, “Interfacing the Archive-City: Situated Installations for Urban Data Visualization,” in Visualizing the Street: New Practices of Documenting, Navigating and Imagining the City, eds. Pedram Dibazar and Judith Naeff (Amsterdam: Amsterdam University Press: forthcoming).

[58] Mattern, “Interfacing Urban Intelligence,” 51; see also Hookway, Interface, 17.

[59] Shannon Mattern, “Mission Control: A History of the Urban Dashboard,” Places Journal(March 2015), https://doi.org/10.22269/150309.

[60] The term ‘social white spots,’ with reference to Architecture, was suggested to us by the attendees of the Imagining [Urban] Data Visualization expert meeting (see [47]). For the notion of ‘sacred spaces,’ see Turkle, Alone Together.

[61] The film is playable from the Boston location in the map feature, which also includes an interview with Turkle (who refers to her classroom as “technically black” – on the white spots map – but actually “pure white”).

[62] Morozov detects a tendency here, which he associates with much of the discourse around ‘digital detox’ and the need for ‘unplugging.’ See Evgeny Morozov, “The Mindfulness Racket: The Evangelists of Unplugging Might Just Have Another Agenda,” New Republic, February 24, 2014, https://newrepublic.com/article/116618/technologys-mindfulness-racket.

[63] This take on the matter is evident also from the documentary that was made as part of the larger White Spots project, entitled “Offline als luxe”or ‘Offline as Luxury’ (VPRO Tegenlicht episode, directed by Bregtje van der Haak, aired May 8, 2016, on NPO, https://www.npo.nl/vpro-tegenlicht/08-05-2016/VPWON_1257578), that includes interviews featuring also in the map function of the app.

[64] John Brownlee, “A Map of Where the Internet Doesn’t Exist – And How to Get There,” CO.DESIGN, July 25, 2016, https://www.fastcodesign.com/3062125/a-map-of-where-the-internet-doesnt-exist-and-how-to-get-there; also, Richard Vijgen, untitled presentation (see [47]).

[65] Mattern, “Cloud and Field.”

[66] This is done even more explicitly in one of the videos (playable from the Washington, DC location on the map), which includes an interview with Morozov on the socio-economic rationale behind said divide.

[67] Helen Kennedy, Rosemary L. Hill, Giorgia Aiello, and William Allen, “The Work that Visualization Conventions Do,” Information, Communication & Society 19, no. 6 (June 2016): 723-24; Mattern, “Cloud and Field.”

[68] See for instance Ben Light, Jean Burgess, and Stephanie Duguay, “The Walkthrough Method: An Approach to the Study of Apps,” New Media & Society, advance online publication (2016), http://dx.doi.org/10.1177/1461444816675438; Mel Stanfill, “The Interface as Discourse: The Production of Norms through Web Design,” New Media & Society 17, no. 7 (July 2015): 1059-1074. Light, Burgess and Duguay speak of the “cultural values” embedded, specifically, in app interfaces; Stanfill argues that interfaces produce “norms.”

[69] Mattern, “Interfacing Urban Intelligence,” 52.

[70] Ibid.

[71] See Charles Taylor’s definition of ‘social imaginary,’ as in his Modern Social Imaginaries (Durham, NC and London: Duke University Press, 2004), 23-30.

Bibliography

Architecture of Radio. “Architecture of Radio: A field guide to the hidden world of digital networks.” Project website. Accessed September 28, 2018. http://www.architectureofradio.com/.

Arnall, Timo, Jørn Knutsen, and Einar Sneve Martinussen. “Immaterials: Light painting WiFi.” Vimeo video, 4:50, February 26, 2011.https://vimeo.com/20412632.

Arnall, Timo, Jørn Knutsen and Einar Sneve Martinussen. “Immaterials: Light painting Wifi.” Significance 10, no. 4 (August 2013): 38-39. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1740-9713.2013.00683.x.

Blinder, Justin. “Wifi Spotting.” Accessed August 18, 2017. http://projects.justinblinder.com/Wifi-Spotting.

Brownlee, John. “A Map of Where the Internet Doesn’t Exist – And How to Get There.” CO.DESIGN, July 25, 2016. https://www.fastcodesign.com/3062125/a-map-of-where-the-internet-doesnt-exist-and-how-to-get-there.

Campbell-Dollaghan, Kelsey. “If Our Eyes Could See Wireless Signals, Here’s How Our World Might Look.” Gizmodo, August 24, 2015. https://gizmodo.com/if-our-eyes-could-see-wireless-signals-heres-what-the-1726215792.

Carr, Nicholas. The Shallows: What the Internet is Doing to Our Brains. New York, NY: Norton, 2010.

Chion, Michel. Audio-vision: Sound on Screen. Translated by Claudia Gorbman. New York, NY: Columbia University Press, 1990.

D’Orazio, Dante. “See the Invisible Wireless Signals Around You with this Augmented Reality App.” The Verge, November 28, 2015. https://www.theverge.com/2015/11/28/9811910/augmented-reality-app-lets-you-see-wireless-signals.

Eriksson, Mats, and Jaap van de Beek. “Is Anyone Out There? 5G, Rural Coverage and the Next 1 Billion.” IEEE CTN, November, 2015. http://www.comsoc.org/ctn/anyone-out-there-5g-rural-coverage-and-next-1-billion.

Galloway, Alexander R. The Interface Effect. Cambridge, UK: Polity Press, 2012.

Google Play. “Architecture of Radio.” Accessed August 22, 2017. https://play.google.com/store

/apps/details?id=nl.richardvijgen.architectureofradioAndroid&hl=nl.

Grugier, Maxence. “The Digital Age of Data Art.” TechCrunch, May 8, 2016. https://techcrunch.com

/2016/05/08/the-digital-age-of-data-art/.

Hookway, Branden.Interface. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press, 2014.

iTunes Preview. “Architecture of Radio.” Accessed August 22, 2017. https://itunes.apple.com/nl

/app/architecture-of-radio/id1035160239?mt=8,

Johnson, Alix, and Mél Hogan, eds. “Location and Dislocation: Global Geographies of Digital Data.” Special issue, Imaginations 8, no. 2 (September 2017). http://imaginations.glendon.yorku.ca/?p=9947.

Johnson, Steven. Interface Culture: How New Technology Transforms the Way We Create and Communicate. New York, NY: Basic Books, 1997.

Kaufman, Michael. “Surrounded By ‘Architecture of Radio.’” Geekdad, November 29, 2015. https://geekdad.com/2015/11/architecture-of-radio/.

Kennedy, Helen, Rosemary L. Hill, Giorgia Aiello, and William Allen. “The Work that Visualization Conventions Do.” Information, Communication & Society 19, no. 6 (June 2016): 715-735.

Kracauer, Siegfried. “Boredom.” In The Mass Ornament: Weimar Essays, translated and edited by Thomas Y. Levin, 331-336. Cambridge, MA and London: Harvard University Press, 1995. First published 1924.

Light, Ben, Jean Burgess, and Stephanie Duguay. “The Walkthrough Method: An Approach to the Study of Apps.” New Media & Society, advance online publication (2016). http://dx.doi.org/10.1177/1461444816675438.

Manovich, Lev. “The Poetics of Augmented Space.” Visual Communication 5, no. 2 (June 2006): 219-240.

Manovich, Lev. “What is Visualization?” Poetess Archive Journal 2, no. 1 (2010). https://journals.tdl.org/paj/index.php/paj/article/view/19/58.

Masson, Eef, and Karin van Es. “Visualizing Connectivity: Data as Evidence in The Architecture of Radio.” First Monday 22, no. 10 (October 2017). https://doi.org/10.5210/fm.v22i10.8039.

Martinussen, Einar Sneve. “Immaterials: Light painting Wifi.” YOUrban, February 22, 2011, http://www.yourban.no/2011/02/22/immaterials-light-painting-wifi/.

Matamoros Fernandez, Ariadna. “Listen to This: Don’t Miss the Sound to Convey Data!” Masters of Media, April 15, 2014. http://mastersofmedia.hum.uva.nl/blog/2014/04/15/listen-to-this-dont-miss-the-sound-to-convey-data-2/.

Mattern, Shannon. “Cloud and Field: On the Resurgence of ‘Field Guides’ in a Networked Age.” Places Journal (August 2014). https://doi.org/10.22269/160802.

Mattern, Shannon. Code and Clay, Data and Dirt: Five Thousand Years of Urban Media. Minneapolis, MN: University of Minnesota Press, 2017.

Mattern, Shannon. “Interfacing Urban Intelligence.” In Code and the City, edited by Rob Kitchin and Sung-Yueh Perng, 49-60. London and New York, NY: Routledge, 2016.

Mattern, Shannon. “Mission Control: A History of the Urban Dashboard.” Places Journal (March 2015). https://doi.org/10.22269/150309.

Morozov, Evgeny. “Only Disconnect: Two Cheers for Boredom.” The New Yorker, October 28, 2013, http://www.newyorker.com/magazine/2013/10/28/only-disconnect-2.

Morozov, Evgeny. “The Mindfulness Racket: The Evangelists of Unplugging Might Just Have Another Agenda.” New Republic, February 24, 2014. https://newrepublic.com/article

/116618/technologys-mindfulness-racket.

Mollerup, Per. Wayshowing > Wayfinding: Basic & Interactive. Amsterdam: BIS Publishers, 2013.

Murphy, David. “iOS App Visualizes the Wireless Signals That Surround Us.” PCMag.com, August 27, 2015. https://www.pcmag.com/article2/0,2817,2490230,00.asp.

Parks, Lisa. “Earth Observation and Signal Territories: Studying U.S. Broadcast Infrastructure Through Historical Network Maps, Google Earth, and Fieldwork.” In New Media, Old Media: A History and Theory Reader, 2nd ed., 92-113. New York, NY and Oxon: Routledge, 2016.

Parks, Lisa. “‘Stuff You Can Kick’: Towards a Theory of Media Infrastructures.” In Between Humanities and the Digital, edited by Patrik Svensson and David Theo Goldberg, 355-374. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press, 2015.

Simmel, Georg.“The Metropolis and Mental Life.” In The Blackwell City Reader, edited by Gary Bridge and Sophie Watson,11-19. Oxford and Malden, MA: Wiley-Blackwell, 2002. First published 1903.

Stanfill, Mel. “The Interface as Discourse: The Production of Norms through Web Design.” New Media & Society17, no. 7 (July 2015): 1059-1074.

Taylor, Charles. Modern Social Imaginaries. Durham, NC and London: Duke University Press, 2004.

Turkle, Sherry. Alone Together: Why We Expect More from Technology and Less from Each Other. New York, NY: Basic Books, 2011.

Van der Haak, Bregtje, dir. VPRO Tegenlicht. “Offline als luxe.” Aired May 8, 2016, on NPO, https://www.npo.nl/vpro-tegenlicht/08-05-2016/VPWON_1257578.

Verhoeff, Nanna. “Interfacing Urban Media Art.” In What Urban Media Art Can Do: Why, When, Where and How, edited by Susa Pop, Tanya Toft, Nerea Cavillo, and Mark Wright, 190-199. Stuttgart: avedition, 2016.

Verhoeff, Nanna, and Karin van Es. “Interfacing the Archive-City: Situated Installations for Urban Data Visualization.” In Visualizing the Street: New Practices of Documenting, Navigating and Imagining the City, edited by Pedram Dibazar and Judith Naeff. Amsterdam: Amsterdam University Press: forthcoming.

Vijgen, Richard. “Life in the Infosphere.” Total Space supplement to volume no. 50 (January 2017): 26-27.

Vijgen, Richard.The Architecture of Radio. iPad app, 2015.

Vijgen, Richard, Bregtje van der Haak, and Jacqueline Hassink. White Spots. iPhone app, 2016.

Whitelaw, Mitchell. “Art Against Information: Case Studies in Data Practice.” The Fibreculture Journal, no. 11 (2008). http://eleven.fibreculturejournal.org/fcj-067-art-against-information-case-studies-in-data-practice/.

White Spots. “White Spots: A Journey to the Edge of the Internet.” Project website. Accessed September 28, 2018. http://white-spots.net/.

Wu, Tim. The Attention Merchants: The Epic Scramble to Get Inside Our Heads. New York, NY: Knopf, 2016.