Sarah Ciston

Media Arts + Practice, University of Southern California

Email: ciston@usc.edu

Reference this essay: Ciston, Sarah. “Misunderstanding as Poetics: Collaborating with AI to Rewrite the Inner Critic.” In Language Games, edited by Lanfranco Aceti, Sheena Calvert, and Hannah Lammin. Cambridge, MA: LEA / MIT Press, 2021.

Published Online: June 15, 2021

Published in Print: To Be Announced

ISBN: To Be Announced

ISSN: 1071-4391

Repository: To Be Announced

Abstract

Language gets morphed continuously by the changing platforms and practices that contain and distribute it—including increasingly prevalent use of AI techniques such as natural language processing (NLP). This calls for new approaches to digital writing, both in criticism and practice. Such approaches can be developed by using AI in artistic contexts and by resituating its texts in unexpected digital–physical spaces—designing interfaces that acknowledge the presence of other embodied users in individual language experiences. Through the close reading of the artistic research project inner(voice)over, which uses a speech-to-text-to-speech chain to “rewrite the inner critic,” this essay considers NLP as a form of mediation, focusing on its gaps in interpretation and sutures of meaning. How does the break of an uncanny word choice introduced by an algorithm open layers of poetic resonance, as well as access tensions of the human–machinic? By collaboratively rewriting inner voices using NLP, this computational artwork explores the opportunities in the imperfections of technological and human communications alike—opening the possibility of influencing each other through language altered across bodies and digital distances. It argues that experimental practices with emerging technology can offer alternative relationships with those technologies, with language, and with each other.

Keywords: Natural language processing, self-compassion, poetics, error, artistic research, digital writing

“what we are engaged in when we do poetry is error”

––Anne Carson, “Essay On What I Think About Most”“Every sound we make is a bit of autobiography.”

––Anne Carson, “The Gender of Sound”

Introduction

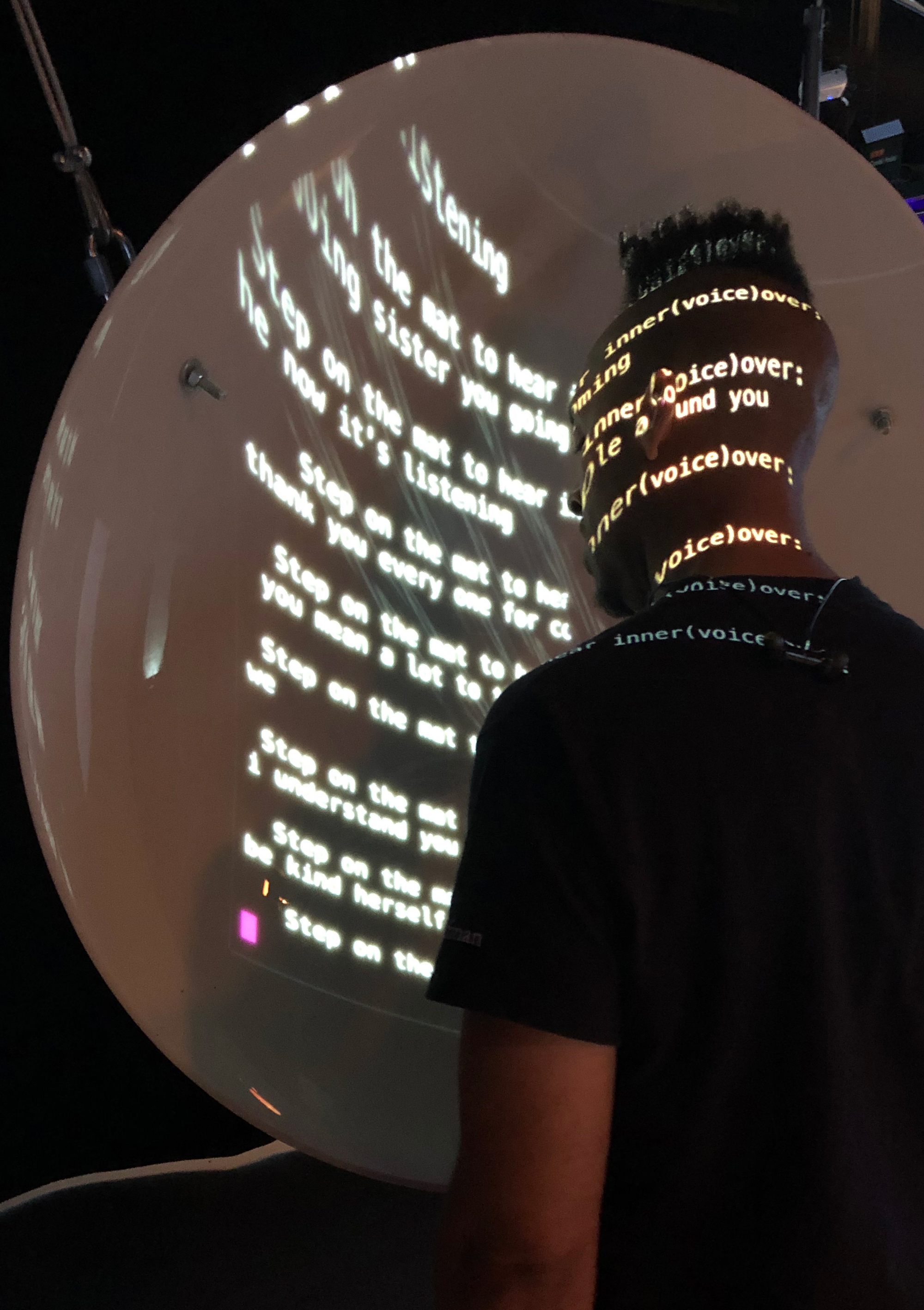

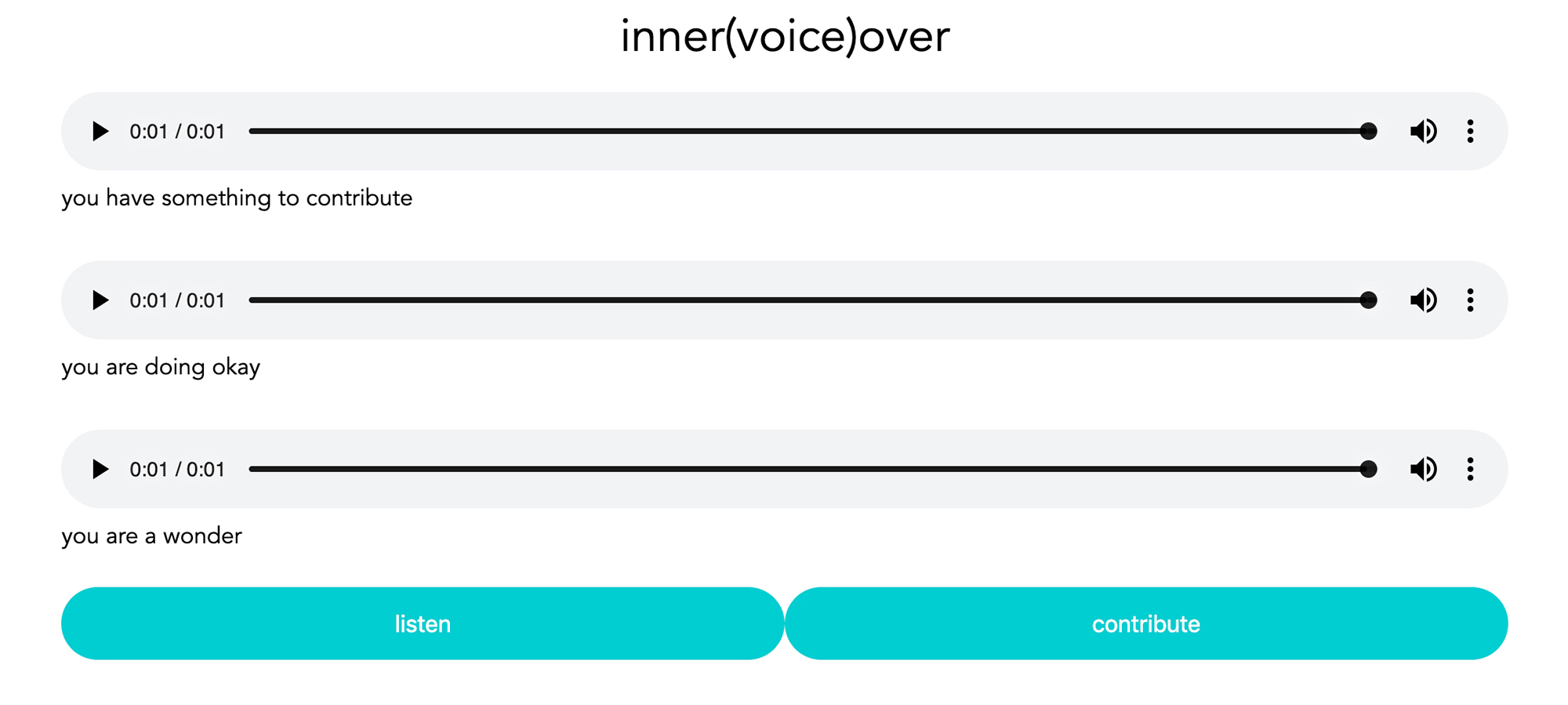

Could artificial intelligence help rewrite the inner critic? inner(voice)over combines speech-to-text analysis and text-to-speech synthesis to engage the inner voice through collaboration and interactive sculpture (Figure 1). This artistic research examines the gaps between what is said and what is heard—the tension between interconnectedness and the inability to understand each other fully. In those gaps, how is meaning transformed? While language has morphed through analog means for millenia, experimental applications of natural language processing (NLP) technologies can help reveal more about how language shapes us in return.

inner(voice)over draws from analog forms—mindful self-compassion research and practice, the tender and uncanny experience of science-museum whisper dishes—but it uses computation to ask: how are bodies processing, absorbing, changed by, and participating in changing language? Could NLP help create interpersonal connections by anonymizing and mediating between users through language; in particular, could it foster increased self-compassion, otherwise difficult for many people to access? [1] How would the introduction of errors—misunderstandings by the NLP system or mispronunciations by users or the system—alter users’ sense of the technology’s infallibility or their own perceptual accuracy, or even create space for poetics? These questions also open up larger questions about what it means to collaborate with artificial systems, while exploring how artistic research practices can generate new approaches to digital writing.

Revising the Inner Critic

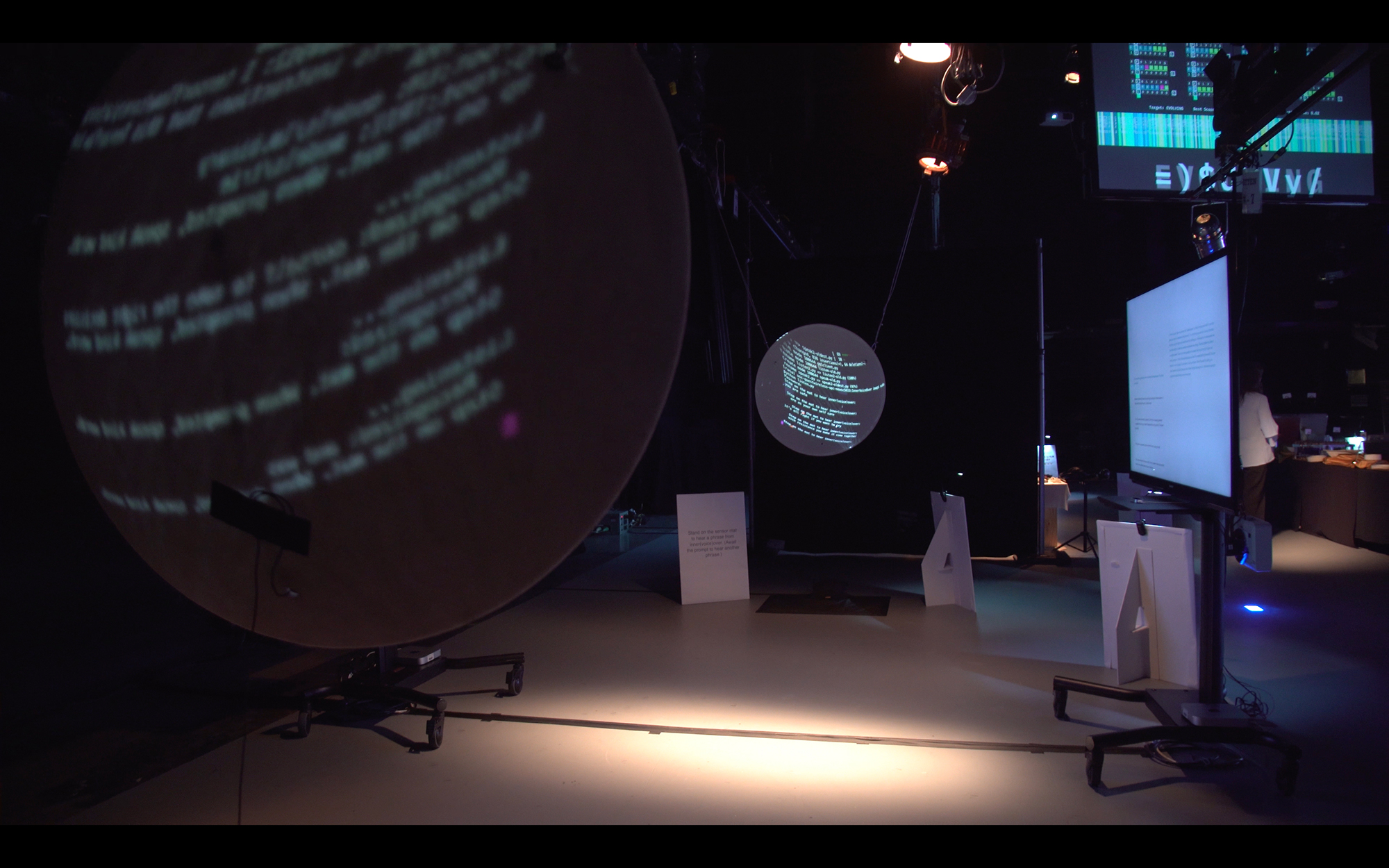

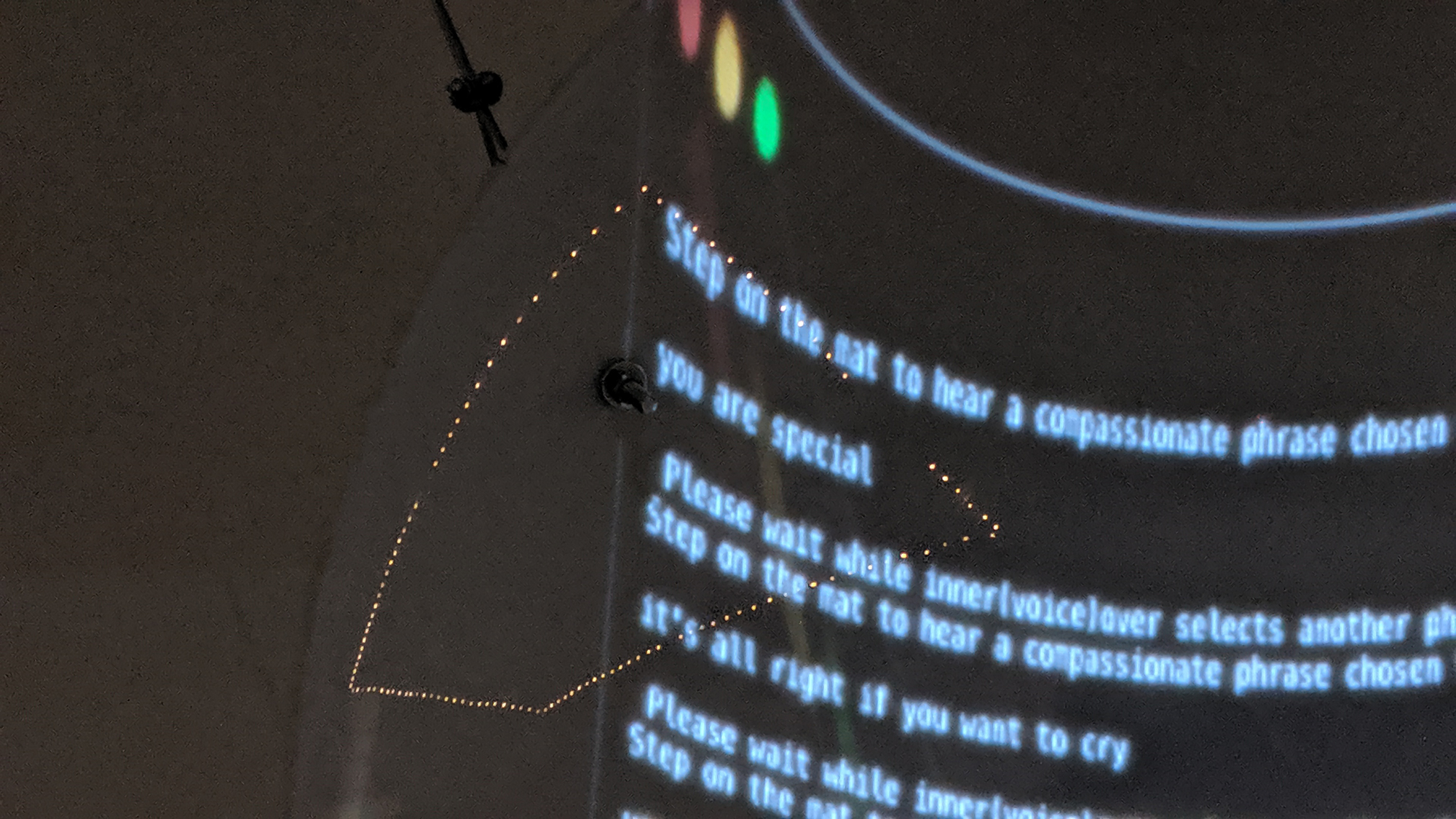

In the inner(voice)over prototype, large plastic dishes hang across from each other approximately 30 feet apart (Figure 2). They create a digital, asynchronous version of the public intimacy of analog acoustic mirrors, which focus sound such that two people can whisper to each other from across open space. Instead, inner(voice)over uses a small microphone in one dish, and in the other dish a set of two audio exciters vibrate to make the dish itself a speaker. Each microphone and speaker is triggered by a pressure sensor on the ground so that users can activate it by stepping close to the dish (Figure 3). Once prompted by text projected onto the dishes (Figure 4), users record kind phrases and inner(voice)over processes them using DeepSpeech speech-to-text analysis and adds them to its database. [2] Then, in across the room, users can hear phrases others have shared, processed using text-to-speech and played as recordings using a synthesized voice created from the artist’s own voice. [3] Through these interactions, users are co-constructing the core of inner(voice)over—its self-compassion database.

Self-compassion involves the ability for individuals to “offer themselves warmth and non-judgmental understanding rather than belittling their pain or berating themselves with self-criticism.” [4] It differs from self-esteem or positive affirmations, because it is not based on evaluation or comparison with others and does not attempt to modify circumstances but rather bring awareness and acceptance to them. [5] A meta-analysis found robust evidence linking more self-compassion to fewer mental health symptoms, increased wellbeing, and resilience to stress. [6] Although self-compassion and self-criticism may each be complex independent responses, researchers are working to study them together because of the compelling links between them: “Developing and enhancing self-compassion through training has significantly reduced self-criticism, shame, and depression in chronically depressed patients and has even improved psychological well-being in healthy individuals.” [7] Building self-compassion has been shown “more effective than other emotion regulation strategies in reducing negative emotions,” including outside Western countries. [8]

Instead of focusing on therapeutic intervention or quantitative research, inner(voice)over examines self-compassion through artistic research, an interdisciplinary mode of qualitative inquiry, experimentation, and creation. [9] This project provides an alternative introduction to self-compassion, especially for people who may be more accustomed to self-criticism. The self-critical mode may have a stronger pull for many people, given the brain’s negativity bias toward seeing danger first to keep itself safe, [10] its confirmation bias reinforcing what it knows already to be true, [11] and influences from culture and parental figures. [12] inner(voice)over uses the metaphor of NLP, and the technology itself, to look at self-compassion through the inner voice, exploring how a positive or negative inner voice is a product of influence and also can inform perceived experience.

The inner voice, or subvocal articulation, is broadly acknowledged and studied, although it necessarily relies on self-reporting. [13] In a survey of current research, common theories about its functions range from executive control of behavior, possibly relaying information between areas of the brain, and bringing thoughts to conscious awareness. [14] Neuroimaging of the left inferior frontal gyrus (LIFG) shows that the inner voice is also connected to one’s sense of self: “empirical evidence establish[es] connections between self-reflection and the inner voice. […P]eople report talking to themselves mostly about themselves.” [15] Further, the negative effects of a cruel inner voice have proven acute, affecting not just mood: “excessive negative inner speech impairs performance whereas more controlled and positive inner speech improves cognitive performance.” [16] Neuroimaging also locates self-criticism and self-compassion in distinct areas of the brain. Self-criticism fired the areas linked to error processing and self-inhibition, while “efforts to be self-reassuring engage similar regions to expressing compassion and empathy towards others.” [17] In sum, research confirms the neural pathways for the inner voice, self-criticism, and self-compassion; and scientific and therapeutic fields seem to agree that efforts to curb excessive negative self-talk through practicing self-compassion are valid and impactful. This artistic research piece acknowledges those fields by asking how AI might mediate a self-compassion practice and make it (counterintuitively) more communal; however, it is important to emphasize that the work’s scope focuses instead on the creative, technological, and critical intersections presented through experimentation with these concepts—and what such speculative interventions may imply for alternative, compassionate and creative uses of AI. [18]

Critics may worry that focus on the self furthers a mentality of individualism, ignoring pressing social issues and reinforcing problematic structures of capitalism. Ronald Purser, author of McMindfulness, argues that both “neoliberalism and the [contemporary Western] mindfulness movement have conceived of social wellbeing in individualistic and psychologized terms.” [19] However, he does not blame mindfulness itself, rather its misuse, which loses sight of interconnectedness: “Neglecting shared vulnerabilities and interdependence, we disimagine the collective ways we might protect ourselves.” [20] That collective call echoes early formulations of the edict “know yourself,” which Michel Foucault traced to its classical meaning “take care of yourself.” [21] He argued this was not always a solipsistic endeavor but instead “one of the main principles of cities” and “the principle on which just political action can be founded.” [22] The work of self-compassion need not be selfish when framed within community. In Living a Feminist Life, Sara Ahmed also addresses this paradox and points to its political potential: “we have to find a way of sharing the costs of that work. Survival thus becomes a shared feminist project.” [23] She argues: “in queer, feminist, and antiracist work, self-care is about the creation of community, […] through the ordinary, everyday, and often painstaking work of looking after ourselves; looking after each other.” [24] Ahmed’s approach that “how we care for ourselves becomes an expression of feminist care” means that practices of self-compassion can be—though of course they are not always—wielded as ethical and political gestures beyond the self. [25] What matters is how one uses the self one cares for. This project suggests self-compassion be built in community, toward critical awareness of our relationships with one another and with technologies, imagining technologies that do not frame quantifiable individualism as their unit of study and goal. It uses natural language processing as both an analogy and an object of study in its own right. Through self-compassion mediated by technology, this artistic prototype plays with shifting the lens of the inner voice and revising it in community; and through the technology’s own errors, both human and AI imperfections can be viewed more critically and creatively.

Error As Poetics

As anyone who has used Siri or Alexa knows, language-driven technologies are prone to error. Interpretive errors in NLP—whether due to algorithm design or parameter selection, or due to user pronunciation or ambient noise, etc.—are not merely a problem to be eradicated by programmers. [26] They disrupt cultural perceptions of AI as infallible, and they serve as reminders that human communication relies on its own interpretive programming. [27] Further, interpretive gaps can open up creative space—allowing for sutures of poetic meaning and for an exploration of digitally mediated relation. Unlike traditional applications of NLP, which focus on reducing error and increasing speed, [28] projects like inner(voice)over suggest an alternative approach to AI that values poetics in the error, resonance in the pause, and co-presence rather than asynchronicity.

In this speech-to-text-to-speech game of telephone, what is lost in translation returns to the user, made meaningful again through creative interpretation. At the recording station of inner(voice)over, each time the program mishears what has been said, that misunderstanding appears projected onto the dish. At the listening station, those errors get reproduced and new errors are introduced. In a twist, sometimes the errors of mishearing and mispronouncing align and sound accurate again, or sound familiar enough for users to infer their intended meaning. Because this process is captured with visual feedback for participating users, they can access the multiple linguistic operations and slippery meanings always operating in artificial and human systems. An uncanny moment of surprise can occur between the user and the project, and between one user and another indirectly.

That expectation-defying moment can be fruitful. As the language inputs and outputs carry multiple levels of meaning simultaneously, this playful near-nonsense activates language in proximity, like poetry. Nathaniel Mackey describes “verbing” as the literary version of “versioning” in Black American jazz improvisation, which emphasizes being in process and in action rather than in a static state: “an emphasis on self-transformation, an othering or, as [Caribbean poet Edward Kamau] Brathwaite has it, an X-ing of the self, the self not as noun but as verb. […] ‘Find the self, then kill it.’ To kill the self is to show it to be fractured, unfixed.” [29] The active work of verbing, of “X-ing the self” happens in the break, in the moment of surprise in which the expected word or sound fails to arrive. Yet the proximity of the unexpected word creates new friction, a kind of perpendicular poetics that expands the field of potential meanings—for language and also for the self.

This poetics is available to interactions with language-based AI just as it is to traditional poetry, whenever an error lets words mean something else or something more through their unexpected proximity. A “digital interstitial aesthetics”—turning the glitch, break, or mistake into a pause for play, creating excess from error—finds poetic value in that perpendicular offshoot, creates more space between words. Anne Carson even calls this space “erotic,” saying that, as a reader, “we stand at an angle to the text from which we can see […] two levels of narrative reality float one upon another, without converging, and provide for the reader that moment of emotional and cognitive stereoscopy which is also the experience of the desiring lover.” [30] While poetry may find erotic energy and creative value in error, cognitive capitalism does not have time for such languid things, and the tension between these approaches becomes important to how technologies are designed and encountered.

Queer Digital Interstitial: The Value of Error in a Language Economy

Thanks to search engines and autocomplete, the space of and between words grows narrow: “in [linguistic capitalism], the basic commodity is not the word but is, instead, the software-ordered space between words.” [31] Proximity itself is monetized. Frederic Kaplan says linguistic capitalism operates to standardize language and draw profit, “When Google’s autocompletion service transforms on the fly a misspelled word, it does more than offer a service. It transforms linguistic material without value (not much bidding on misspelled words) into a potentially profitable economic resource.” [32] That is, it standardizes your language into concepts and objects you can shop for.

Warren Sack describes this effect at scale as the “computational episteme” during which, in both analog and digital disciplines, language no longer represents, but is analyzed as if meaningless: “An extreme formalism of this kind has taken hold in natural language processing, information retrieval, machine learning, and other software-based approaches now commonly applied to indexing, searching, and—most importantly—ordering the language spaces of the Internet.” [33] In contrast, attending to an error in a speech recognition tool through a digital interstitial aesthetic reclaims space for the non-commodity to create other kinds of value, such as poetry.

This digital interstitial aesthetic draws on Jenny Sundén’s theory of queer disconnection, which finds in lost cell signals and SMS ellipses new opportunities for non-heteronormative relation. [34] In moments that run counter to the myth of constant digital connection as an endless, relentless stream of information, Sundén makes space between the digital data packets to catch a breath. She argues for non-linear, queer connections that fundamentally include disconnection as part of their texture and vibrancy. [35] This suggests the option of alternative interrelations that are mediated with technology. Thus, I argue for a “queer digital interstitial” reading that allows connections and new meanings to emerge from the vectors of error, excess, and erotic found in the gaps and breakdowns of the digital packet and the whispered phrase.

Conclusion: Co-Writing with AI

When language is being instrumentalized—multiplicitous and hyperreactive, executing and executed upon, moving at speeds perceived as instantaneous—an experimental art practice can still utilize the affordances of AI toward alternative goals, through the invitation for users to engage with AI differently. Sarah Kember and Joanna Zylinska theorize media and mediation as embodied networks of relations, rather than as separate instances of humans and tools. [36] Given NLP’s new role in media creation and consumption, and the ways in which its artificial voices have already entangled with human users’, it is no stretch to consider how we actively collaborate and co-write with AI.

Many writers and artists undertake collaborative practices with digital technology—from Allison Parrish’s Compasses to Lauren McCarthy’s “Social Turkers”—and claim varying degrees of authorship over their creations. [37] Along with intentional creations, a theory of embodied mediation allows the addition of practices which those involved may not consider as writing or collaborating with AI directly. The economic and affective circuits involved in using these technologies are much larger than an imagined one-to-one relationship between user and artificial agent; instead, they include thousands of humans who knowingly or unknowingly contribute everything from their anonymous posts and tweets to the very timbre of their voices. [38] For example, the DeepSpeech tool used for this project was built using various existing text and voice corpora as well Mozilla’s own Project Common Voice, an open-source corpus created using voice contributions from approximately 40,000 people at the time of this writing. [39]

It is essential to be aware of the extended community that co-creates each NLP system, both in consideration of potential bias and as a network of co-authors. Vladimir Todorović and Dejan Grba argue that in generative writing, even in analog aleatoric systems such as those of Oulipo poems, “If we do not consider the system and if we don’t envision the operation of this simple generative platform, our reading and interaction with the piece will be limited. […] The content of this type of works includes the generative system […].” [40] They suggest the expository and expressive power of a generative narrative comes partly from the reader’s understanding of its computational workings. Combining this with Kember and Zylinska’s approach to media, collaborating with AI requires a reading of the media object that extends it to include both form and content (indistinguishably interwoven), as well as an embodied network of creators and users (with those roles increasingly blurred).

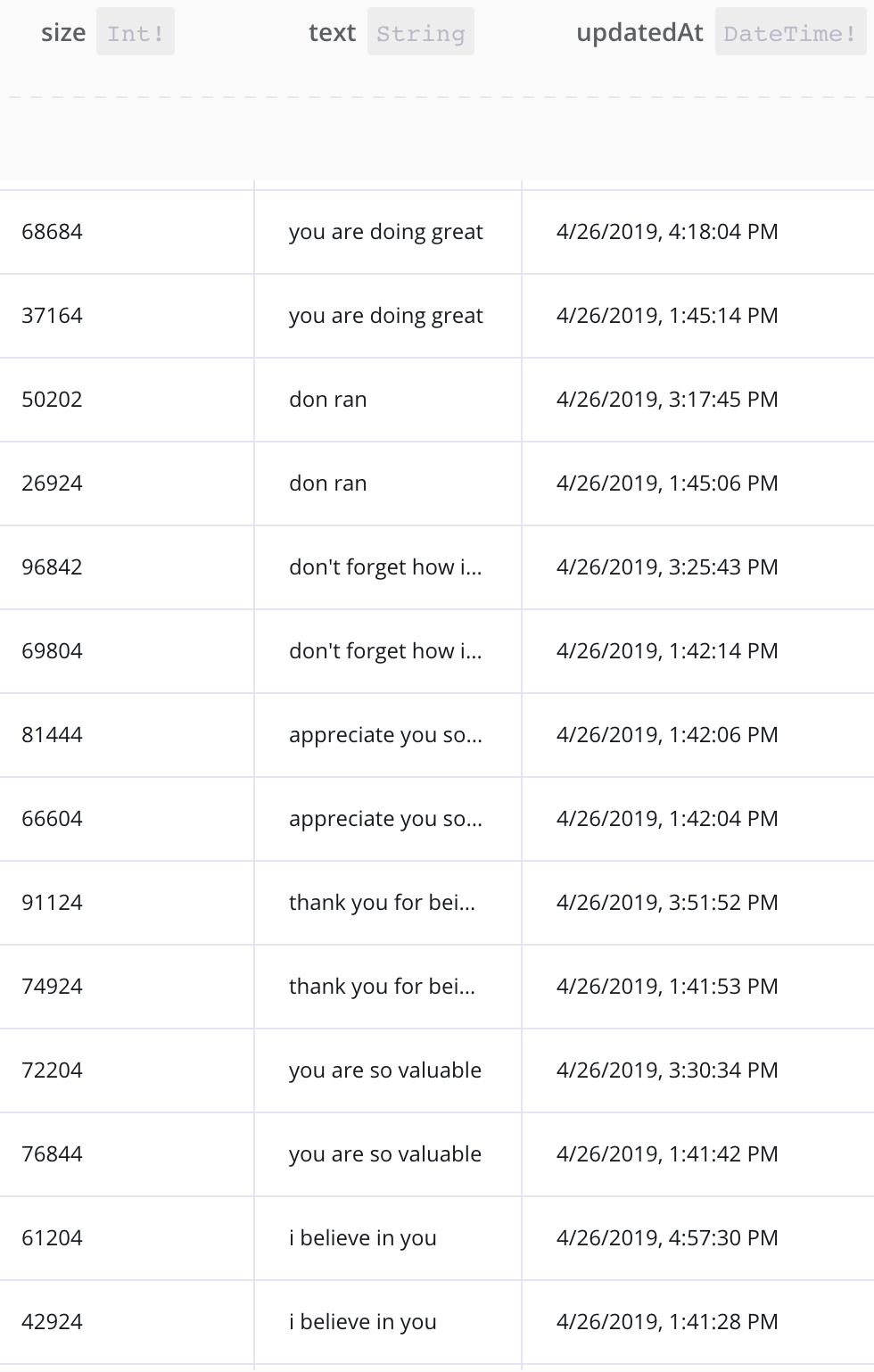

If NLP tools and inner voices are both created socially, inner(voice)over attempts to reimagine and rewrite them socially as well. In its structure as an AI-mediated but community-driven interactive piece, it highlights NLP’s potential and its errors, while emphasizing how user voices are already entangled, echoing each other’s influence. The interactive sculpture inserts a technological gap between users which it helps to close, creating a language space of possibility and an interpersonal space for care. By engaging a strange synthesized voice, it offers a new way to hear “you are so valuable” (Figure 5, Figure 6). [41] At first, such compassion may sound like a glitch. But part of the practice is to learn to incorporate error. Elizabeth Wilson asks if error must mark the limit of an artificial system or if there are more useful ways to incorporate such breaks into its operating principles: “Is error (and […] shame and anger and contempt) the limit of an artificial system, or […] Might there be artificial systems that can tolerate their own inadequacies?” [42] This question echoes self-compassion practices that do not try to eliminate suffering but instead acknowledge its presence. [43] And since “error” originates from the Latin “to wander,” perhaps poetic engagements with NLP errors allow a little extra space to wander, with each layered meaning and compassionate reframing, each perpendicular path. By experimenting with digital writing through computational media projects like inner(voice)over, user-creators rework language, joyfully showing what language technologies cannot do. These errors reflect the gaps in human understanding too—as we write and rewrite in interdependence—X-ing the self yet again.

Author Biography

Sarah Ciston (she/they) is a Mellon Fellow and PhD Candidate in Media Arts and Practice at the University of Southern California and a Virtual Fellow at the Humboldt Institute for Internet and Society in Berlin. Their research investigates how to bring intersectionality to artificial intelligence by employing queer, anti-racist, anti-ableist, and feminist theories, ethics, and tactics. They also lead Creative Code Collective—a student community for co-learning programming using approachable, interdisciplinary strategies. Their creative-critical code-writing projects include an interactive poem of the quantified self and a chatbot that tries to explain feminism to online misogynists. They are currently developing an Intersectional AI Toolkit that includes a zine library and a code resource hub.

Notes and References

[1] Kristin D. Neff, Kristin L. Kirkpatrick, and Stephanie S. Rude, “Self-Compassion and Adaptive Psychological Functioning,” Journal of Research in Personality 41, no. 1 (February 2007): 140.

[2] A TensorFlow Implementation of Baidu’s DeepSpeech Architecture: Mozilla/DeepSpeech, C++ (2016; repr., Mozilla, 2019), https://github.com/mozilla/DeepSpeech.

[3] Lyrebird • Ultra-Realistic Voice Cloning and Text-to-Speech, https://lyrebird.ai/.

[4] Neff, et al. “Self-Compassion.”

[5] Ibid.

[6] Angus MacBeth and Andrew Gumley, “Exploring Compassion: A Meta-Analysis of the Association between Self-Compassion and Psychopathology,” Clinical Psychology Review 32, no. 6 (August 1, 2012): 551.

[7] Caroline J. Falconer, John A. King, and Chris R. Brewin, “Demonstrating Mood Repair with a Situation-Based Measure of Self-Compassion and Self-Criticism,” Psychology and Psychotherapy: Theory, Research and Practice 88, no. 4 (December 2015): 357.

[8] Kohki Arimitsu and Stefan G. Hofmann, “Effects of Compassionate Thinking on Negative Emotions,” Cognition and Emotion 31, no. 1 (January 2, 2017): 166.

[9] Natalie Loveless, How to Make Art at the End of the World: A Manifesto for Research-Creation. (Durham: Duke University Press Books, 2019): 7–9.

[10] Paul Rozin and Edward B. Royzman, “Negativity Bias, Negativity Dominance, and Contagion,” Personality and Social Psychology Review 5, no. 4 (November 1, 2001): 296.

[11] Raymond S. Nickerson, “Confirmation Bias: A Ubiquitous Phenomenon in Many Guises,” Review of General Psychology 2, no. 2 (June 1998): 175–220.

[12] C. Irons et al., “Parental Recall, Attachment Relating and Self-Attacking/Self-Reassurance: Their Relationship with Depression,” British Journal of Clinical Psychology 45, no. 3 (2006): 306.

[13] Agustin Vicente and Fernando Martinez Manrique, “Inner Speech: Nature and Functions,” Philosophy Compass 6, no. 3 (2011): 209.

[14] Ibid, 122–214.

[15] Alain Morin and Breanne Hamper, “Self-Reflection and the Inner Voice: Activation of the Left Inferior Frontal Gyrus During Perceptual and Conceptual Self-Referential Thinking,” The Open Neuroimaging Journal 6 (September 7, 2012): 78.

[16] M. Perrone-Bertolotti et al., “What Is That Little Voice inside My Head? Inner Speech Phenomenology, Its Role in Cognitive Performance, and Its Relation to Self-Monitoring,” Behavioural Brain Research 261 (March 15, 2014): 231.

[17] Olivia Longe et al., “Having a Word with Yourself: Neural Correlates of Self-Criticism and Self-Reassurance,” NeuroImage 49, no. 2 (January 15, 2010): 1849.

[18] Sarah Ciston, “Intersectional AI Is Essential: Polyvocal, Multimodal, Experimental Methods to Save Artificial Intelligence,” Journal of Science and Technology of the Arts 11, no. 2 (December 29, 2019): 3–8.

[19] Ronald Purser, McMindfulness: How Mindfulness Became the New Capitalist Spirituality (London: Repeater, 2019): 34.

[20] Ibid., 45.

[21] Foucault, Michel. Technologies of the Self: A Seminar with Michel Foucault. Edited by Luther H. Martin, Huck Gutman, and Pattrick H. Hutton. (Amherst, Mass: Univ. of Massachusetts Press, 1988): 19, 22.

[22] Ibid., 25.

[23] Ahmed, Sara. Living a Feminist Life. (Durham: Duke University Press, 2017): 236.

[24] Ibid., 240.

[25] Ibid., 237.

[26] Ruben Morais, “A Journey to <10% Word Error Rate––Mozilla Hacks––the Web Developer Blog,” Mozilla Hacks––the Web developer blog, November 29, 2017, https://hacks.mozilla.org/2017/11/a-journey-to-10-word-error-rate.

[27] Ed Finn, What Algorithms Want: Imagination in the Age of Computing (Cambridge, MA: MIT Press, 2017).

[28] Morais, “A Journey to <10%.”

[29] Nathaniel Mackey, “Other: From Noun to Verb,” Representations, no. 39 (1992): 60.

[30] Anne Carson, Eros the Bittersweet: An Essay (Princeton University Press, 2014): 85, 171.

[31] Frederic Kaplan, “Linguistic Capitalism and Algorithmic Mediation,” Representations 127, no. 1 (August 1, 2014): 59.

[32] Ibid.

[33] Warren Sack, “Out of Bounds: Language Limits, Language Planning, and the Definition of Distance in the New Spaces of Linguistic Capitalism: Computational Culture,” Computational Culture: A Journal of Software Studies, no. 6 (November 28, 2017).

[34] Jenny Sundén, “Queer Disconnections: Affect, Break, and Delay in Digital Connectivity” Transformations, no. 31 (2018): 63–78.

[35] Ibid., 73.

[36] Sarah Kember and Joanna Zylinska, Life after New Media: Mediation as a Vital Process, Reprint edition (Cambridge, MA; London, England: The MIT Press, 2014): 178.

[37] Allison Parrish, Compasses, Sync. an Ongoing Artistic Journal in Digitally Published Zines, 2.27, 2019; Lauren McCarthy, Social Turkers, http://socialturkers.com/.

[38] “Common Voice by Mozilla,” https://voice.mozilla.org/.

[39] Sean White, “Announcing the Initial Release of Mozilla’s Open Source Speech Recognition Model and Voice Dataset,” The Mozilla Blog (blog), https://blog.mozilla.org/blog/2017/11/29/announcing-the-initial-release-of-mozillas-open-source-speech-recognition-model-and-voice-dataset.

[40] Vladimir Todorović and Dejan Grba, “Helping Machines (Help Us) Make Mistakes: Narrativity in Generative Art” (xCoAx 2019: Conference on Computation, Communication, Aesthetics & X, Milan, Italy, 2019): 8.

[41] Sarah Ciston, inner(voice)over Database, http://innervoiceover.com/ .

[42] Elizabeth A. Wilson, Affect and Artificial Intelligence (Seattle: University of Washington Press, 2011), 57.

[43] Neff, et al., “Self-Compassion.”

Bibliography

Ahmed, Sara. Living a Feminist Life. Durham: Duke University Press, 2017.

Arimitsu, Kohki, and Stefan G. Hofmann. “Effects of Compassionate Thinking on Negative Emotions.” Cognition and Emotion 31, no. 1 (January 2, 2017): 160–67.

A TensorFlow Implementation of Baidu’s DeepSpeech Architecture: Mozilla/DeepSpeech. C++. 2016. Reprint, Mozilla, 2019. https://github.com/mozilla/DeepSpeech.

Carson, Anne. Eros the Bittersweet: An Essay. Princeton University Press, 2014.

Ciston, Sarah. “inner(voice)over Database.” http://innervoiceover.com/

––––––. “Intersectional AI Is Essential: Polyvocal, Multimodal, Experimental Methods to Save Artificial Intelligence.” Journal of Science and Technology of the Arts 11, no. 2 (December 29, 2019): 3–8.

“Common Voice by Mozilla.” https://voice.mozilla.org/.

Falconer, Caroline J., John A. King, and Chris R. Brewin. “Demonstrating Mood Repair with a Situation-Based Measure of Self-Compassion and Self-Criticism.” Psychology and Psychotherapy: Theory, Research and Practice 88, no. 4 (December 2015): 357.

Finn, Ed. What Algorithms Want: Imagination in the Age of Computing. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press, 2017.

Foucault, Michel. Technologies of the Self: A Seminar with Michel Foucault. Edited by Luther H. Martin, Huck Gutman, and Pattrick H. Hutton. Amherst, MA: University of Massachusetts Press, 1988.

Irons, C., P. Gilbert, M. W. Baldwin, J. R. Baccus, and M. Palmer. “Parental Recall, Attachment Relating and Self-Attacking/Self-Reassurance: Their Relationship with Depression.” British Journal of Clinical Psychology 45, no. 3 (2006): 297–308.

Kaplan, Frederic. “Linguistic Capitalism and Algorithmic Mediation.” Representations 127, no. 1 (August 1, 2014): 57–63.

Kember, Sarah, and Joanna Zylinska. Life after New Media: Mediation as a Vital Process. Reprint edition. Cambridge, MA; London, England: The MIT Press, 2014.

Longe, Olivia, Frances A. Maratos, Paul Gilbert, Gaynor Evans, Faye Volker, Helen Rockliff, and Gina Rippon. “Having a Word with Yourself: Neural Correlates of Self-Criticism and Self-Reassurance.” NeuroImage 49, no. 2 (January 15, 2010): 1849–1856.

Loveless, Natalie. How to Make Art at the End of the World: A Manifesto for Research-Creation. Durham: Duke University Press Books, 2019.

Lyrebird.Ultra-Realistic Voice Cloning and Text-to-Speech. https://lyrebird.ai/.

MacBeth, Angus, and Andrew Gumley. “Exploring Compassion: A Meta-Analysis of the Association between Self-Compassion and Psychopathology.” Clinical Psychology Review 32, no. 6 (August 1, 2012): 545–52.

Mackey, Nathaniel. “Other: From Noun to Verb.” Representations, no. 39 (1992): 51–70.

McCarthy, Lauren. Social Turkers. http://socialturkers.com/.

Morais, Ruben. “A Journey to <10% Word Error Rate––Mozilla Hacks––the Web Developer Blog.” Mozilla Hacks––the Web developer blog, November 29, 2017. https://hacks.mozilla.org/2017/11/a-journey-to-10-word-error-rate.

Morin, Alain, and Breanne Hamper. “Self-Reflection and the Inner Voice: Activation of the Left Inferior Frontal Gyrus During Perceptual and Conceptual Self-Referential Thinking.” The Open Neuroimaging Journal 6 (September 7, 2012): 78–89.

Neff, Kristin D., Kristin L. Kirkpatrick, and Stephanie S. Rude. “Self-Compassion and Adaptive Psychological Functioning.” Journal of Research in Personality 41, no. 1 (February 2007): 139–54.

Nickerson, Raymond S. “Confirmation Bias: A Ubiquitous Phenomenon in Many Guises.” Review of General Psychology 2, no. 2 (June 1998): 175–220.

Parrish, Allison. Compasses. Sync: An Ongoing Artistic Journal in Digitally Published Zines, 2.27, 2019.

Perrone-Bertolotti, M., L. Rapin, J. -P. Lachaux, M. Baciu, and H. Lœvenbruck. “What Is That Little Voice inside My Head? Inner Speech Phenomenology, Its Role in Cognitive Performance, and Its Relation to Self-Monitoring.” Behavioural Brain Research 261 (March 15, 2014): 220–39.

Purser, Ronald. McMindfulness: How Mindfulness Became the New Capitalist Spirituality. London: Repeater, 2019.

Radford, Alec, Jeffrey Wu, Rewon Child, David Luan, Dario Amodei, and Ilya Sutskever. “Improving Language Understanding with Unsupervised Learning.” OpenAI Blog (blog), June 11, 2018. https://openai.com/blog/language-unsupervised/.

Rozin, Paul, and Edward B. Royzman. “Negativity Bias, Negativity Dominance, and Contagion.” Personality and Social Psychology Review 5, no. 4 (November 1, 2001): 296–320.

Sack, Warren. “Out of Bounds: Language Limits, Language Planning, and the Definition of Distance in the New Spaces of Linguistic Capitalism: Computational Culture.” Computational Culture: A Journal of Software Studies, no. 6 (November 28, 2017).

Sundén, Jenny. “Queer Disconnections: Affect, Break, and Delay in Digital Connectivity” Transformations, no. 31 (2018): 63–78.

Todorović, Vladimir, and Dejan Grba. “Helping Machines (Help Us) Make Mistakes: Narrativity in Generative Art.” xCoAx 2019: Proceedings of the Seventh Conference on Computation, Communication, Aesthetics and X. Milan, Italy, 2019.

Vicente, Agustin, and Fernando Martinez Manrique. “Inner Speech: Nature and Functions.” Philosophy Compass 6, no. 3 (2011): 209–19.

White, Sean. “Announcing the Initial Release of Mozilla’s Open Source Speech Recognition Model and Voice Dataset.” The Mozilla Blog (blog). https://blog.mozilla.org/blog/2017/11/29/announcing-the-initial-release-of-mozillas-open-source-speech-recognition-model-and-voice-dataset.

Wilson, Elizabeth A. Affect and Artificial Intelligence. Seattle: University of Washington Press, 2011.