Daniele Balit

Curator, Art Historian

Email: danielebalit1@gmail.com

Web: www.dbarchives.net

Reference this essay: Balit, Daniele. “On Sound Display and Other (Bird)Cages.” In Sound Curating, eds. Lanfranco Aceti, James Bulley, John Drever, and Ozden Sahin. Cambridge, MA: LEA / MIT Press, 2018.

Published Online: December 15, 2018

Published in Print: To Be Announced

ISBN: 978-1-912685-55-4 (Print) 978-1-912685-56-1 (Electronic)

ISSN: 1071-4391

Repository: To Be Announced

Abstract

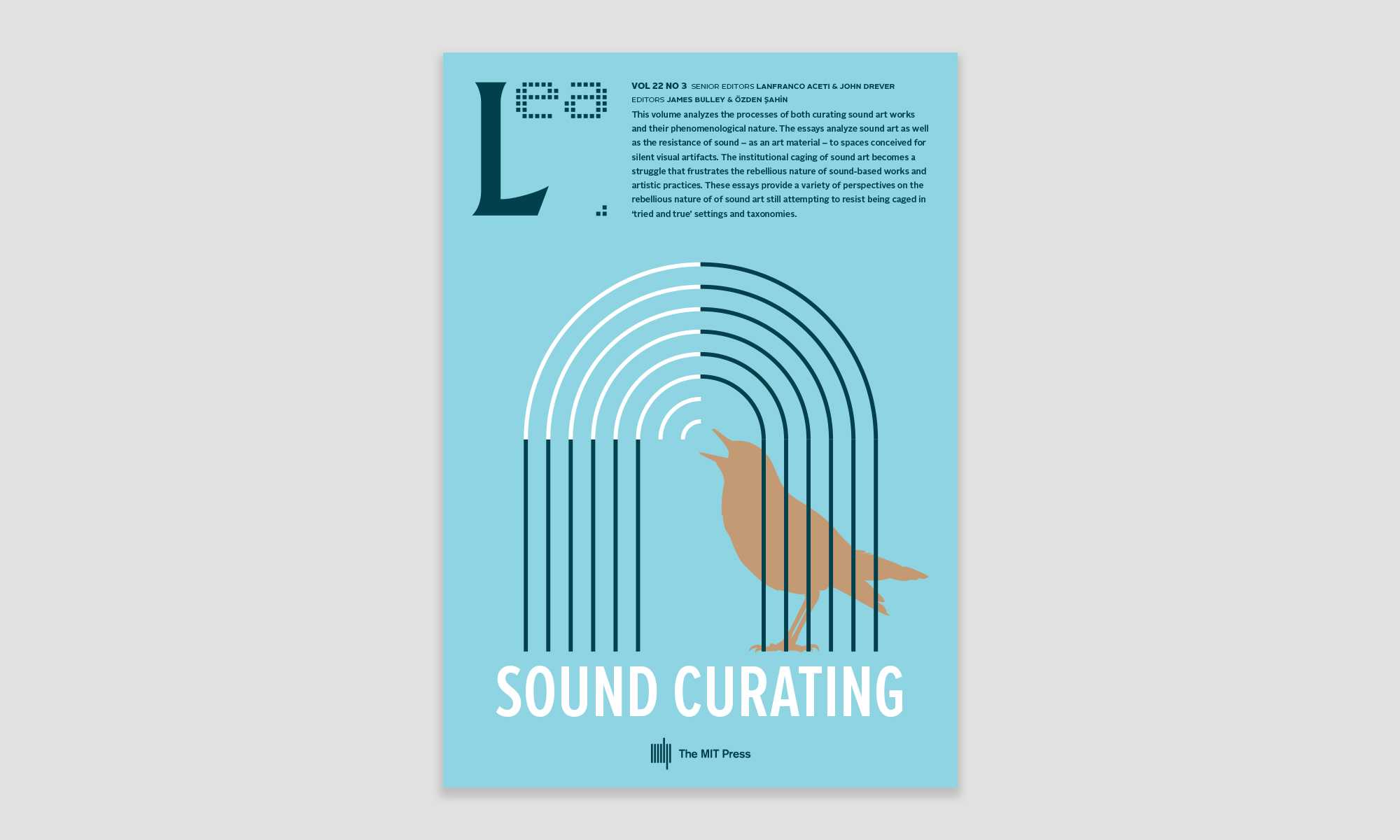

Birdcage is a curatorial experiment initiated in 2009 as an itinerant and temporary sound-based exhibition space traveling around the globe. It is a gallery that constantly redefines itself to respond to the contexts in which it settles for each episode and through dialogue with participating artists. Focusing on the immateriality of sound, Birdcage challenges site and gallery-space as settled notions, to reconsider them within a broader network of relations and social factors. This paper discusses the curatorial position at the basis of this project and investigates some of its methodological implications. The curatorial experience of the author is contextualized by a selection of historical examples: Robert Smithson, Max Neuhaus, Yves Klein, and Michael Asher, all of whom allow to identify some issues related to the advent of sound art. From this standpoint, the author aims to critically discuss the contemporary practice of exhibiting sound, its institutional confinements, and its potential relocation into the territory of the everyday. Amongst the questions raised in this discourse are whether historical attempts to rethink the listening experience can be inherited, adapted and reinvested, as key methodologies for the contemporary curator.

Keywords: Curating, institutional critique, site-specific exhibitions, contextual art, Robert Smithson, Michael Asher, Max Neuhaus, Yves Klein, avant-garde (1960s / 1970s)

Introduction to the Cultural Prison

In 1972, the artist Robert Smithson refused an invitation to participate in Documenta 5, the Kassel based exhibition curated, for its fifth edition, by Harald Szeemann and Jean-Christophe Ammann. Smithson instead contributed a critical statement to the exhibition catalogue, in which he accused curators and art institutions of being the origin of a “cultural confinement.” In the eyes of Smithson, the direction taken by Szeemann for Documenta 5 was an affirmation of the curator-as-author role, an act of self-legitimation that hindered artistic freedom and reinforced the position of the curator. By creating “fraudulent categories,” shows like Documenta 5 in Kassel were for Smithson a way for curators to impose their own limitations on the artists. Smithson regarded this practice as a deception: the curatorial apparatus was to be kept out of the artist’s control, and acted upon them as a “cultural prison.” [1]

Belonging to the years of institutional critique, Szeeman’s curation of Documenta 5 has been contested by numerous artists and theorists, yet Smithson’s position seems particularly uncompromising:

“Museums, like asylums and jails,” he adds, “have wards and cells – in other words, neutral rooms called ‘galleries.’ A work of art, when placed in a gallery loses its charge, and becomes a portable object or surface disengaged from the outside world. A vacant white room with lights is still a submission to the neutral.” [2]

Smithson’s words bring to mind the writings of French philosopher Michel Foucault and induce to consider the museum as part of the structures identified and described by Foucault as modern institutions of confinement, such as the prison, the clinic, or the asylum. [3] The curator would then be an intrinsic mechanism of a system of discipline and codification. As the “warden” of an art system increasingly absorbed by the laws of consumerism, the curator is there to fulfill a specific function: to separate art from the rest of society – as stated by Smithson who then adds:

“Next comes integration. Once the work of art is totally neutralized, ineffective, abstracted, safe, and politically lobotomized it is ready to be consumed by society. All is reduced to visual fodder and transportable merchandise. Innovations are allowed only if they support this kind of confinement.” [4]

Curatorial Confinement

Smithson’s statement in the Documenta 5 catalogue raises important points when reflecting on the practice of ‘curating sound’. His charge, that curators are stifling artists with fraudulent categorization, is reminiscent of the concerns that American artist Max Neuhaus (a pioneer of site-based sound installation) has expressed. In 2000, Neuhaus wrote in protest at the widespread use of the term ‘sound art’ by exhibition curators: “Much of what has been called ‘Sound Art’ has not much to do with either sound or art”. [5] He noted that the curators use such categories for promotional reasons, resulting in a reductive, medium-specific approach. For Neuhaus this curatorial hegemony blurred distinctions, rather than facilitated the fine-tuning which he saw as an essential part of the aesthetic experience. Comparing these statements by Smithson and Neuhaus is interesting: both are artists who belong to the years of the neo-avantgardes in New York, both were concerned with the role of curators, and both felt the need to highlight their concerns about what may be termed a ‘curatorial confinement’ – whether such confinement should be intended as a physical one (the museum) or linguistic (the production of categories). What can be spotted from these analogies is a common effort to question the hierarchy of the artist-curator relationship. Hence, the first real conflict between artists and curators was related to the issue of defining the boundaries of the aesthetic experience.

From this perspective, and particularly if we consider the crafting of new sound practices, it is relevant to spot the resonances between Smithson’s description of the spaces of the museum as neutral cells that make art ineffective with the writings of the Canadian composer and author, R. Murray Schafer. Noting that the presentation of music has become an activity that demands silence, in 1992 Schafer defined the concert hall as a “container of silence”. He then states:

“In fact it would be possible to write the entire history of European music in terms of walls, showing not only how the varying resonances of its performance spaces have affected its harmonies, tempi and timbres, but also to show how its social character evolved once it was set apart from everyday life.” [6]

In the same text, we see Schafer too connecting this idea of segregating music from reality to a broader cultural context, as we are faced once more with a parallel between language and architecture. As Smithson and Neuhaus, Schafer seems to be concerned with the use of categories, and particularly with those of ‘sound’ and ‘music’. While in so many non-European languages such distinction is absent, as he highlights in the Occidental culture the separation of the two terms reflects, on a linguistic level, the architectural, indoor character of the European musical tradition.

Whether silent chambers or neutral galleries, the spaces deliberately built for the aesthetic experience, are there to protect art from any external influences, and can only hinder its integration into society and life. If the artistic experimentations of the neo-avantgardes have tried to dismantle a modernist tradition deep-rooted both in music and visual art, curators seem to have been left behind in their struggle with the ambiguities of their role, as today they can often still be considered as the wardens of the institutional system.

However, if we think to the sonic field, it must be reminded that of the distinguishing aspects of the new aesthetic associated with sound-based practices, was a strong aspiration to de-neutralize the site of the listening experience. Sound art aimed to build a new form of communication between indoor spaces and immanent reality. This drive was prefaced by the work by the American artist John Cage. By removing the aural attention from the stage, his famous composition 4’33” from 1952 implicitly called for a concert hall to be left with its windows open so that the audience might listen beyond the limits of the musical space. [7] The aim to open the chamber of the concert hall to its exterior environment finds a very literal and gallery-based incarnation in the work Clocktower (1976) by the artist Michael Asher. Asher removed the doors and the windows of a New York gallery: a dismissal of the modernist dogma of the isolated and enclosed gallery-space. Asher let outside agents, including sound, intrude upon the art display system: a continuation of the topos of his earlier works, to which we will return later on in this paper.

Yet before doing so, we should consider another aspect of Smithson’s argument against the ‘curatorial confinement’: the separation of art from the rest of society. In the process of submitting the object to the neutrality of the white cube, not only is the outside world excluded, but the work becomes a form of transportable merchandise. In other words, an art object disengaged from the relations to a specific context becomes formatted for a global system and its market, as it can easily be transported and exhibited anywhere within the same neutral conditions. If we consider the institutionalization of sound in recent years, and the accompanying plethora of medium-based exhibitions and festivals, a question that can be asked is whether sound, despite its immateriality, is becoming another ‘object’, a neutralized and transferable commodity treated, like most of the gallery-objects, with conventional indoor modalities (but often – it must be said –with the lack of the specific knowledge necessary in sound and acoustics). Moreover, exhibitions like the recent Soundings at the MoMA (2013), or Sound Art. Sound as a Medium of Art, at the ZKM (2012-13) seem to be endeavors to delimit sonic practices in the regimental and legitimating range of the white cube. The windows left open by Cage and the sonic explorations of Schafer, Neuhaus, and Asher, seem to be closing once again.

But this discourse is not a binary one, with artists on one side and the curators and galleries on the other. The non-linearity of Smithson’s own practice pays testament to that. Despite his virulent and provocative words, we can find in his position a nuance and complexity: often he adopts an open, dialogical process in relation to the gallery-space and to ideas of confinement. Smithson’s position, rather than a simple denial of the gallery and its machinations, can be properly seen as an attempt to forge new relationships with the institution. Whilst he stood against commodification and institutional homologation, and questioned the portability of the object and the neutrality of the modernist gallery, he also proposed that artists should create a new and stronger relation with site, by finding ways to include the context of their art within their work. When the curator “imposes his own limits”, not allowing the artist to “set his limits”, it is up to the artist to do it, and Smithson ventured a site-based, contextual approach. [8]

These kinds of positions, which questioned and probed at the status of the gallery, the siting of an artwork, and the curatorial relationship therein, were a defining influence on the curatorial statement that originated the Birdcage project: to create a temporary and nomadic exhibition space that would invite artists to define the context and the modalities of their intervention. At its core, the Birdcage project produces site-based interventions, and involves the artists in defining the whole protocol for the exhibition of their work: from the contextual elements to the discursive ones and the communication negotiating the visibility and the specific audience for each episode. The project acts as a platform for exploring the notion of site, moving beyond conventional site-specific strategy and focusing on the selection of site as part of the artistic process. In other words, the idea is not to assign a pre-existing site to the artist, but to define and activate a situation through a process of artistic decisions, curatorial work, and through negotiation with different partners. As Smithson once said, the study of the selection of site is an art in itself at its very beginning. [9]

Max Neuhaus’ practice was of particular inspiration in the creation of the Birdcage project, and his works LISTEN (1966) and Times Square (1977) provided a framework for focusing on notions of site, context and a wider notion of situation intended as a network of relations and social factors. For these pieces Neuhaus developed a constellation of elements specific to his ‘extramural’ endeavor; a number of agents that expanded the field of the work beyond its location. As indoor counterparts for his site-specific outdoor works, he created diptych drawings that he saw as a form of “statement of idea” that was capable to convey a different experience of the work; he commissioned posters and other print material to provide further context, such as the silk-screened poster for Walkthrough (1973-77), or the various printed materials related to LISTEN. In the later years of his life, he also used his website to clarify the contextual aspects of his artworks. Neuhaus did not only unfold a wider field for the works through print and text, but he also created an expanded sense of site by making ways of remotely controlling his installation works. He implemented sophisticated remote systems in order to monitor and calibrate the way in which the works responded to the ambient sound – an important practicality, particularly in the case of his permanent sound installations. [10]

Neuhaus’ practice adds complexity to conventional notions of site, and ventures innovative tools for exhibiting sound in public space. In his work, the dualism between inside and outside display is replaced by a network of elements which constitute an overall site for the work. We are provided with the example of an artist who sought to have the choice to control all aspects of the processes of production, distribution, and reception of his work. The adoption of curatorial strategies within Neuhaus’ art practice was, therefore, a necessity related to the context-oriented character that notably defines his sound practice and the constant relocation, and site-related modulation, of the listening experience.

Voids

In 1958, at the Iris Clert gallery in Paris, Yves Klein presented his seminal exhibition entitled La Spécialisation de la sensibilité à l’état matière première en sensibilité picturale stabilisée. With this title, which can be translated as “The Specialization of Sensibility in the Raw Material State into Stabilized Pictorial Sensibility”, Klein described what became know as his “exhibition of the void”. The exhibition consisted in what he called a dematerialization of the painting, and its transformation into a pure “pictorial sensible state”. Klein’s attempt was to abolish the limits between the painting and the exhibition space: by forming a “climate” or an “environment”, the new pictorial state that he experimented was affecting the “sensible bodies of the visitors” through an “invisible, intangible and radiating” action. [11] As art historian Jean-Marc Poinsot has pointed out, it is important to consider Klein’s exhibition as not simply a statement of intent, or as a purely conceptual thought. [12] In the days before the opening Klein spent 48 hours inside the gallery, painting everything white (to clean the gallery from “the impregnations of the numerous previous exhibitions”), preparing the environment for the “stabilization” of the intended pictorial state. [13] He also modified the access to the gallery, and defined a complex ceremonial for the vernissage. Hence, rather than a conceptual provocation, Klein’s void should be considered more as a material process, requiring a complex organization in order to appropriate and transform a specific context.

By exhibiting the void, Klein questioned the relationship between the gallery-space and the artwork, and showcased the use of curatorial strategies in his practice. The distinctions between work, space and context were reconsidered, and various elements of the conventional curatorial process were incorporated within the work, something that resonates with Smithson’s later claim for a total control of the elements that mediate between the artist, the work and the audience. It is important to notice how such appropriation of the context, and of the curatorial, is not realized only through a conflictual opposition to the institution. On the contrary, Klein collaborated closely with Iris Clert, the owner of the gallery. Their collaborative dialogue allowed him to define every aspect of the exhibition: from the wording and design of the invitations, to the posters, from the opening event, to the fabric of the curtains surrounding the entry to the gallery-space itself. Paradoxically, Klein’s void acted as a way to deneutralize the gallery-space: disclosed as a site of social and institutional relations, the gallery became the object of contextual investigations, offering some “raw material” to artistic and curatorial practice.

Such shifting attention to the context and to the presentation of art, to some extent explains the reasons of the wide influence of Klein’s work on numerous conceptual artists of the late 1960s and early 1970s. The practice of the Californian artist Michael Asher is particularly significant in that sense. In December 1969, Asher created a piece for the Spaces exhibition at the MoMa in New York. [14] He invited the audience to experience, as in the case of Klein, an empty space, a seemingly simple, experiential work. Pretty much as Klein’s action, the emptiness of the space resulted from a highly considered physical process of transformation. Asher made structural changes to the room, dampening its acoustic and adding two extra walls to create additional open entrances and exits to the space. Within the room the majority of sounds heard were from outside of the space (as its internal architecture was muffled). For Asher, this situation created a heightened auditory attentiveness that brought to attention contextual aspects of the museum environment that the audience would not normally pay attention to: how they navigated its spaces, explored its structures and considered its underlying soundscape.

Other works by Asher have proposed even more radical relationships between gallery-space, artwork and the outside world. In both the aforementioned installation work Clocktower (1976) and in his work Installation (1970) at Pomona College in California, Asher dramatically altered the gallery architecture to remove the separation between inside and outside environmental spaces. Asher also explored the removal of boundaries between working spaces and exhibiting spaces in galleries, exemplified in his 1974 installation at the Claire Copley Gallery in Los Angeles. There, the art gallery’s hidden business operations were exposed, both visually and acoustically, by the removal of a wall. However, even when Asher has used the architecture of the gallery as ‘material’ from which to pronounce institutional critique, it is important to register that this has always taken place in close collaboration with the institution itself: these works are still, very much, ones of collaboration and compromise within those galleries and alongside the curators who hosted and commissioned them.

Birdcages

Such historical examples demonstrate how some artists have introduced new models for their practice in an effort to establish a new and more dynamic relation between the exhibition and curation of their work and the heterogeneous social territories and realities that concern them. We can consider these new models that arose in the visual arts in parallel to a similar ‘turn’ that occurred in sound practice in the same era. From the futurism of Luigi Russolo’s noise machines, to the work of John Cage and Max Neuhaus, a framework has unfolded that seeks to counter the long tradition of isolating music from “the outside world” – to recall Smithson’s terms once again. After John Cage ended the quarantine of music from sound, radically broadening the field, Max Neuhaus and Michael Asher sought to realize this model, initiating a new cohabitation between sound and everyday life. A way to relocate the artistic experience, and to rethink its modes and contexts, in order to prevent, we might say, any kind of cultural, architectural, and curatorial confinement.

In 2009, I instigated the curatorial project Birdcage to further investigate these kinds of issues, and encourage the exploration of different configurations and possible ways of propagation in artistic practice. I sought to initiate new relations between the experience of listening and our everyday existence.

The integration of sounds into everyday life was at the forefront of the project proposed for Birdcage by the Beijing-based artist Yan Jun in 2009. Yan Jun sought to infiltrate his sounds into the daily environment of an office space. Inspired by instructions written by William S. Burroughs, Yan Jun set up, hidden in some desks of a very messy youth journal office in Beijing, a system of recorders, mp3 players, cassette Walkman and earbuds. Through these he activated a variety of sound processes, including capturing the sounds of the office and playing them back in real time causing the creation of feedback noises, and replaying interviews selected from the archives of the journal. Yan Jun produced what he described to the author as some “small sounds about this room and about people who work in the room.” [15]

The episode realized in 2009 by Carl Michael von Hausswolff in Stockholm, explored the integration of sound works into everyday life was. Hausswolff proposed to situate his work titled 1485.0 kHz, a streaming sound device, in the dining room of his neighbor, the Swedish artist Jan Håfström. The protocol defined by Hausswolff prescribed that the device would be turned on only when Håfström invited guests over to his house for dinner. By means of generating a particular sound stream frequency, the device is designed to allow visitors to hear voices from the ‘other side’, a technique inspired by the ‘audioscopic’ investigation of the Danish researcher Frederich Jurgenson and his longtime attempts at communicating with the spirit world.[16] The intervention into Håfström’s dining room aimed at reconfiguring a private space by opening a ‘door’, allowing for a different type of social space and communication. Moreover, it was the act of listening itself that became the object of a specific attention.

Both Yan Jun and Carl Michael von Hausswolff’s projects demonstrate how the decisions related to the selection of a specific context in which to host a sound work can have an impact on a wide range of factors that are generally external to its parameters. These include the type of audience, the temporal and locative modes of access to the work, the communication strategies before and after the event, and the way auditory information is distributed. Such adjustments, which are normally part of the curatorial process, become influenced, if not defined, by artistic decisions and processes. The curatorial research developed through the Birdcage episodes is an attempt to challenge the separation between the roles, something that finds a counterpart in the negation of the neutrality of the exhibition display. As a chameleonic gallery-space Birdcage is a way to explore the capacity of sound to transform a place and to define the context in which a work is sited in as an integral part of the work in itself.

Other Birdcage projects have further interrogated the use, appropriation and reconfiguration of alternative spaces for performance and listening. Birdcage: Zedejik, an episode proposed by Takuro Mizura Lippit that took place in Amsterdam on July 4, 2009, consisted of the temporary use of an empty store and its front window located in Zedejik street, a street which is a mash-up of Asian cultures, surrounded by coffee shops and the windows of the Red Light District. A specifically designed stage was installed in order to distribute the performers (all active members of the experimental music scene and all of Asian descent living and working in the Western world) on both the vertical and horizontal axes of the indoor space. As a manner to think about ways of presenting the artistic experience, the stage can be seen as a hybrid object: a way to integrate some curatorial decisions in the project. Furthermore, the installation explored the dynamic between the audience looking in and listening from the outside juxtaposed with the experience of both the audience and the performers within the space. This type of space allowed the creation of different forms of interplay between sound and vision, as notions of transparency and interface between exterior and interior were the main focus in Lippit’s proposal, exploring different ways of listening within the politics of the gaze. [17]

The episode devised by Angelo Petronella in 2011, took possession of a private apartment in Milan. This electroacoustic piece, which was experienced both as performance and installation, played with the decentralization and circulation of a variety of sound-spaces – the visitors moving along from room to room over the two floors of the apartment, experiencing different kinds of acoustics and contexts. With his stage installed in the living room and facing a cluster of custom-designed small speakers sitting on a coffee-table, Petronella was controlling and modulating his piece, as well as providing the smooth transitions between the live performance and the autonomous composition. In the case of the ‘trilogy’ of episodes realized by the New York-based Japanese performer Aki Onda over three years in Paris (2011—2013), the works were developed over an extended period as a result of a residency and several trips in Paris, during which Onda was able to develop a more in-depth contextual investigation related to each episode. Onda is a collector of soundscapes, captured during his travels using his Walkman. Birdcage allowed him to experiment with something different from his usual performances in venues. Onda sought to achieve a more context driven framing for his performances which would focus on interacting with the acoustics, memories, histories and socialities of a series of specifically selected locations. The final performances were realized in places with markedly different architectural, acoustic and social characteristics. These sites included the Cour Carrée of the Louvre (a semi-public space with a distinctive acoustic that was incorporated in an extended-duration sound experience), the African neighborhood of La Goutte d’Or (where Onda realized a sound-walk punctuated with some performances in selected outdoor areas (fig. 1)), and the Chapel of Saint Augustin at the National Art Academy in Paris (a building that hosts a collection of replicas of Italian Renaissance artworks including Michelangelo’s Last Judgement and Verrocchio’s Colleoni and that was flooded with Onda’s saturated noise). The way in which the aural memory affect our perception of space, with its different temporalities and with either the clashes or the idiosyncrasies that it can produces, was an active agent in Onda’s projects for Birdcage, challenging any fix approach to site. Not differently from a re-enacted memory, the experience of site is always the result of a negotiation between the individual and a larger community. The art of site selection seems to have done some considerable progresses since the time of Smithson’s concerns. And the conflict between the curatorial and the artistic spheres seem to have found a much more dialogical space in such type of contextual investigations.

When thinking of the idea of experimenting with a gallery “without walls”, it is difficult not to refer to the famous definition proposed by French author and politician André Malraux in his 1947 book Le Musée imaginaire where he advocates for an art liberated from the institutional segregation of the museum’s walls, through the use of photographical reproduction. Rather than reinforcing a ‘curatorial confinement’, a space and attitude that imposes its own hierarchical limits on the artist and their work, as highlighted by Smithson and Neuhaus, the aim for Birdcage has been for a collaborative artistic-curatorial process from the outset of each episode. Quoting Malraux seems to raise a question that goes beyond the different contexts and mediums, as the project highlights a vital question: does the gallery of today really need to exist as a static physical place, or can the utilization of tools and strategies including web documentation, social networking, flexible collaboration and a challenging but open-minded approach to space be a suitable (and sometimes even more appropriate) means for the production and distribution of sound works?

In our time of information society and global networks, the relationship between site and non-site seems now even more complex and relevant to consider than in the era of artists like Robert Smithson and Max Neuhaus. The dispersion and immateriality of the art object have evolved new conditions for art practice: a work can now be considered as inhabiting a cluster of different places and temporalities. Likewise, we cannot speak any more of a singular place, but rather of a ‘dispersed’ and ‘networked’ place, or perhaps what is sometimes called a “discursive” place. [18] If artists like Neuhaus, Smithson and Asher can be seen to have mapped new territories for artistic exploration, questioning the modes and practices of exhibiting sound seems to be an effective way to create a continuity with this legacy. Sound is a medium that escapes any fixed time-space relation, and which is hard to confine, to enclose within any bound: an ideal tool for an operative contextual investigation. Thinking about a site-based listening experience is a way to provide us with new insights into these territories and to continue a rigorous investigation into the role of the gallery-space and how that relates to sound art practitioners.

Author Biography

Daniele Balit is an art historian, theoretician and curator. He teaches Art History at the Institut Supérieur des Beaux-Arts de Besançon in Besançon. He is associate researcher at the TEAMeD laboratory at Paris 8 University. As a specialist in sound studies, his research focuses in particular on the audio-visual convergences of the post-Cage , and on the contextual and site specific practices. He holds a Ph.D. at Paris 1 – Panthéon-Sorbonne University and was awarded with a research grant in theory and art criticism by the Cnap (Centre national des arts plastiques) for a research on the artist Max Neuhaus. He is the co-editor of the anthology Les pianos ne poussent pas sur les arbres (Pianos don’t grow on threes – words and writings by Max Neuhaus), to be published by Les presses du réel in March 2017. His article “From Ear to Site – On Discreet Sound” was published by MIT Press in Leonardo Music Journal, (n°23, 2013), followed by « Pour une musique écologique – Max Neuhaus » in Critique D’Art n°44, Printemps/Été, 2015. He is a founder member of the curatorial platform 1:1projects in Rome, of the collective OuUnPo, and initiator of Birdcage, an itinerant and temporary sound gallery. His recent curatorial projects include Blow-up (Paris, Jeu de Paume, 2012), No Music Was Playing (Montreuil, Instants Chavirés – Brasserie Bouchoule, 2014), Red Swan Hotel (Rome, MACRO, 2015), Wetlands Hero (Chatou, Cneai, 2015), Max Feed (Besançon, Frac Franche-Comté, 2016) and Mix Feed (Besançon, Institut Supérieur de Beaux Arts: 2016).

Notes and References

[1] Robert Smithson, “Cultural Confinement,” (1972) in Robert Smithson, the Collected Writings, ed. Jack D. Flam (Berkeley: University of California Press, 1996), 154.

[2] Ibid.

[3] For a reading of the museum institution in “Foucault’s terms”, see Douglas Crimp, On the Museum’s Ruins, (Cambridge, MA: MIT Press, 1993).

[4] Robert Smithson, op. cit., 154-55.

[5] Max Neuhaus, “Sound Art?” in Volume: Bed of Sound, (New York: P.S.1 Contemporary Art Center, 2000). Republished in: http://www.max- neuhaus.info/soundworks/soundart (accessed February 22, 2014).

[6] Cf. Raymond Murray Schafer, “Music, Non-Music and the Soundscape,” in A Companion to Contemporary Musical Thought Vol. 1, ed. John Paynter, Tim Howell, Richard Orton and Peter Seymour (London and New York: Routledge, 1992), 35.

[7] The image of the auditorium with the windows left open comes from Branden W. Joseph analysis of Cage’s aesthetics and refers to Cage’s compositions, that “like a glass house, to use one of Cage’s favorite metaphors […] emulated a type of acoustical ‘transparency’ to external events that undermined their separation and their autonomy”. Cf. Branden W. Joseph, Beyond the Dream Syndicate: Tony Conrad and the Arts after Cage: a «Minor» History (New York: Zone Books, 2008), 79.

[8] Robert Smithson, op. cit., 154

[9] Robert Smitshon, “A Thing Is a Hole in a Thing it is Not,” (1968) in Robert Smithson, the Collected Writings… op. cit., 96.

[10] See the interview made by Neuhaus on the occasion of the inauguration of a site-specific sound installation that Neuhaus created at the Menil Collection, Sound Figure, 2007, where he speaks about the password-protected website that he uses to control his works remotely: “Max Neuhaus” (interview, The Artists Documentation Program (ADP), The Menill Foundation, Houston, TX, May 2, 2008), available online at: http://adp.menil.org/?page_id=296 (accessed March 10, 2016).

[11] Klein’s terms come from a conference given at La Sorbonne University in 1959, as quoted by Jean-Marc Poinsot in: Jean-Marc Poinsot, “Deux expositions d’Yves Klein,” in Quand l’œuvre a lieu : l’art exposé et ses récits autorisés (Dijon: Les presses du réel, 2008), 72.

[12] Cf. Jean-Marc Poinsot, op. cit., 63-79. Poinsot’s essay (and the rest of the book) was particular inspiring for this paper, as he is particularly concerned about the question of site in relation to the exhibition display.

[13] Cf. Klein quoted by Poinsot, op. cit., 73.

[14] See the press release, the publication and other documentation material related to the 1969 Spaces exhibition curated by Jennifer Licht, available online at the “Exhibition history” section of the MoMa web site: https://www.moma.org/calendar/exhibitions/2698 (accessed December 30, 2016).

[15] See Yan Jun’s interview with the author, January, 2010, available at the Birdcage web site: http://birdcagespace.com/index.php?/episode/news-for-tomorrow-report (accessed March 10, 2016).

[16] See the CD compiled for the exhibition “Friedrich Jürgenson from the Studio for Audioscopic Research” at Färgfabriken, Stockholm, Sweden (2000) and curated by Hausswolff himself: Jürgenson, Friedrich, From The Studio For Audioscopic Research, Parapsychic Acoustic Research Cooperative and Ash International, 2000, CD.

[17] See the press release available at the Birdcage web site resulted from a text provided by Lippit himself: http://birdcagespace.com/index.php?/episode/dj-sniff (accessed March 10, 2016).

[18] Cf. James Meyer, “The Functional Site,” in Space, Site, Interventions – Situating Installation Art, ed. Erika Suderburg (Minneapolis, MN: University of Minnesota Press, 2000), 23-37.