Barbara London

Yale University School of Art

Email: barbaralondon32@gmail.com

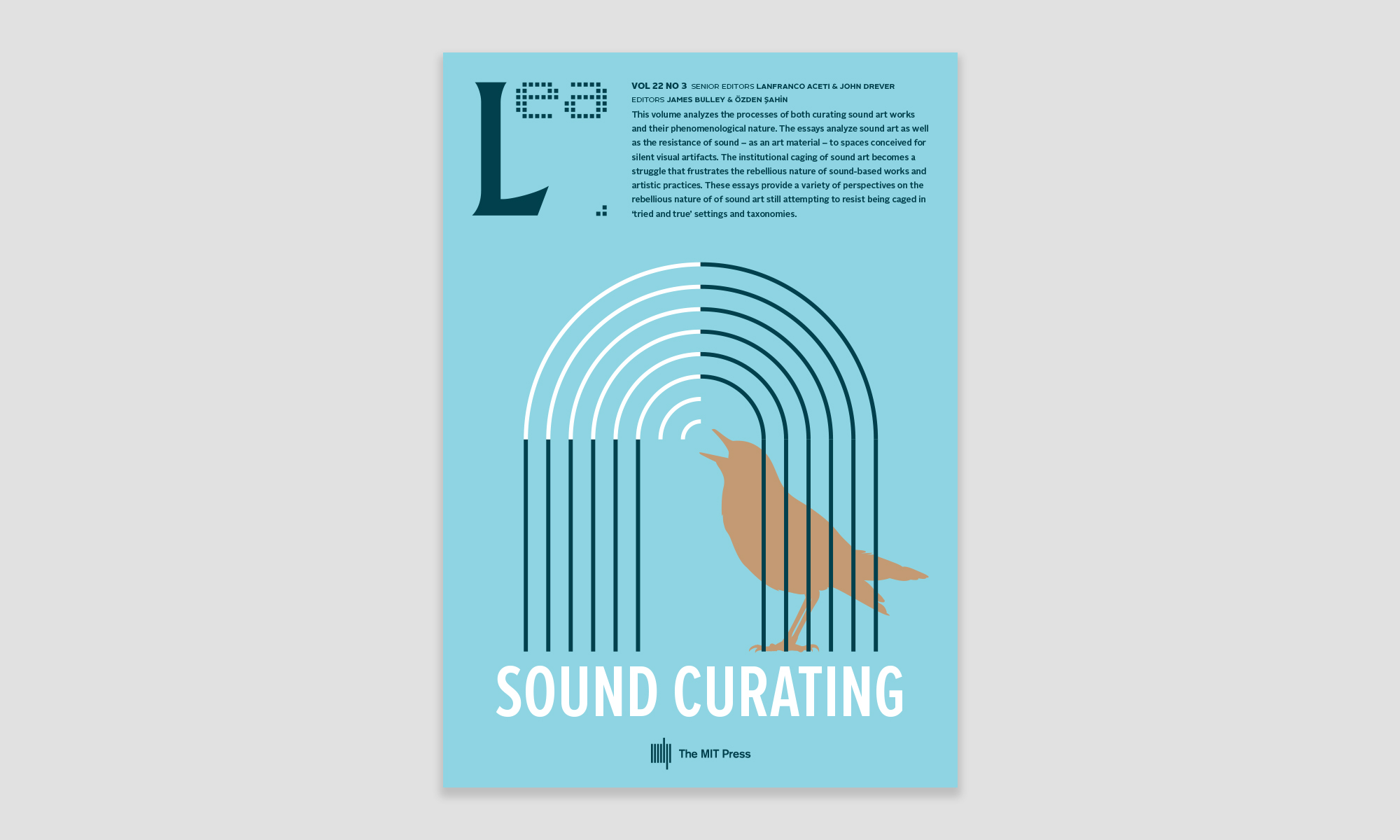

Reference this essay: London, Barbara. “Media Art Retools.” In Sound Curating, eds. Lanfranco Aceti, James Bulley, John Drever, and Ozden Sahin. Cambridge, MA: LEA / MIT Press, 2018.

Published Online: December 15, 2018

Published in Print: To Be Announced

ISBN: 978-1-912685-55-4 (Print) 978-1-912685-56-1 (Electronic)

ISSN: 1071-4391

Repository: To Be Announced

Abstract

Barbara London examines how the electronic arts challenged the white cube. Back in the 1970s, art museums operated with twentieth century, object-oriented categories. Meanwhile installation with its spatial, site specificity, Performance with its abstract notions of duration, and video art and electronic music with their manipulation of the electronic signal challenged convention, propelling contemporary art beyond the limitations of a museum gallery’s four walls. London discusses factors that facilitated museums’ gradual support of video and sound. Time, moving image, and sound became pliable materials; concerts morphed into open-ended environmental installations. She concludes with Soundings: A Contemporary Score, the show she organized at MoMA (August 10–November 3, 2013).

Keywords: video art, sound art, media art, music video, Barbara London, Marco Fusinato, Richard Garet, Jacob Kirkegaard, Camille Norment, Tristan Perich, Susan Philipsz, Hong Kai Wang, Jana Winderen, Captain Beefheart, the Residents, Nam June Paik, David Bowie, Sonic Youth, Tony Oursler, Tony Conrad, Laurie Anderson, Perry Hoberman

An Introduction to My 1970’s Manhattan Universe

From the get go, Manhattan was the center of my universe. My curatorial career began at MoMA in the early 1970s, when international phone calls were expensive and audio cassettes cheap. New York City was bankrupt, the art world small, no one had money, yet energy and ideas soared.

The counter-culture and revolution that radicalized the 1960s compelled privileged modern art institutions like MoMA to accommodate ‘alternative’ forms generated by a broad range of artists. Pursuing boundary-breaking practices, some revolving around music in new kinds of permutations, artists picked up the first portable video cameras and recording decks, and in modernist fashion explored the specifics of the newly accessible medium. Their time-based (and therefore intangible and difficult to collect) art grew, nurtured by the seat-of-the-pants-style, artist-run, rough and ready venues that were sprouting up in metropolises everywhere. Turning away from the past and stridently debunking everything, warring camps conducted ideological battles: minimalists versus expressionists, video-makers versus filmmakers, punkers versus heady theorists.

As a young contemporary curator I focused on the hot potato of video, about which little was written beyond the prescient alternative magazines Radical Software, Avalanche, and Satellite Video Exchange. Artists crisscrossed disciplines to experiment with the medium’s protean forms. Video unfolded in two tiers as technology advanced rapidly. At the top stood the professional broadcast industry, closed for decades to the nonunion ‘amateur’ until British, German, French government, and Public Television stations held the studio door ajar for a select few. At the ‘low’ end, artists pooled resources and shared new-to-the-market consumer video gear, inventively forging creative possibilities for raw, performative narratives.

Curatorial research meant seeking out artists. I doggedly wanted to know the how and why someone made a work. I was curious about related projects, be it someone’s artist books or their part in an evolving punk band’s LP. I asked locals what they had seen on recent travels while doing gigs in London, Berlin, or Tokyo. If they taught, I asked to preview videos and sound art by their best students. More than fonts of information, artists were important collaborators as I developed video and sound art’s position at MoMA. Museumgoers became participants and were engaged in a more active relationship with media.

I climbed musty staircases in derelict buildings way downtown. I made studio visits with artists like Nam June Paik, who thrived on experimentation and surprise. Recycling was a fundamental aspect of Paik’s work for practical (economic) and aesthetic reasons, with the TV set as a core building block. Dropping by his studio meant crawling over and through a maze of electrical wires, tubes, and old circuitry to reach the artist standing in rubber boots, so as not to be electrocuted.

Most nights I attended ad hoc screenings and performance events. Artists arrived with their latest tape tucked under their arms, having spent days torqueing clunky portable video gear and switchers to tweak images of themselves carrying out an action alone in the studio. I sat on a tinny folding chair upstairs at Artists Space and watched Laurie Anderson do a live vocal track to a just-back-from-the-developing-lab super-8 film. I sent far-away artists letters asking about their latest work and waited patiently, often weeks or months, for replies.

Back then time was a stretched out, tangible material that swallowed you up. Jack Smith would start his soirées by passing around a joint. The performance really began as he put on and took off different garments grabbed out of a mound of clothes piled up on the floor at the center of his loft. Events lasted long into the night. At 5 a.m., Michael Snow or Joan Jonas or Robert Wilson might be the only audience left.

My own sense of cultural possibilities opened up in 1974, when Nam June Paik introduced me to John Cage and Merce Cunningham. I often think about their approach to life – the center of the world is where you stand. These artists shared an unusual openness to culture from non-Western parts of the world, to new forms, and respect for the visions of young collaborators. Towards the end of his life, Cunningham learned new computer software to choreograph his company’s dances.

Consumer video gear meant that artists as well as garage bands with homegrown agendas were equipped to play with image and sound, and the dream of democratic and total media distribution as well. Yet this anarchic enterprise simultaneously paralleled the rise of the short-format music video as a promotional tool for musicians and record labels. In 1970, Captain Beefheart (aka Don Van Vliet) garnered free time on public-access cable television in Los Angeles and aired the promo he had made for his new album, Lick My Decals Off, Baby. In a scant ninety seconds, a TV announcer refers to band members by their oddball names as he performs Clarabell-like madcap actions. A hand tosses cigarette butts through the air, and then, sporting a fez, Beefheart’s bandmate Rockette Morton paces, winding an eggbeater. Echoing William Wegman’s concurrent short vignettes made in his studio with his dog, Beefheart’s prototypical music video draws on the contingent rhythm of slapstick. Just as his musical sound was an eclectic sampling of shifting time signatures (influenced by free jazz) and Frank Zappa (Beefheart’s close friend and collaborator), this initial video exploration resonated with the surrealistic character of psychedelic environments, such as Joshua White’s well-known light shows at the Fillmore East in New York, which accompanied the pitch distortion and feedback of Jimi Hendrix and others. Beefheart’s videos introduced a bizarre instance of both interruption and continuity into broadcast-television programming.

Beefheart got in early, and musicians paid attention: as the nascent music video slowly emerged as an effective marketing vehicle for the recording industry, its forms and outlets were left wide open. Following Beefheart, the Residents (based in San Francisco), for example, were anticipating a broad audience for music videos and believed that they could shape the format-less to sell records, though, than to infiltrate systems of television and radio promotion. Their famous 1976 album The Third Reich ‘n’ Roll features Dick Clark in an SS uniform holding a carrot on the record cover. De-skilled tracks started out with pilfered clips of classic rock and funk songs that were spliced, overdubbed, and layered with new instrumentation. To accompany the songs, the group immediately produced brief music videos (after having attempted, from 1972 to 1976, to film the first long-format music video; this was never released in its entirety). These shorts were shot on film and initially screened in art-house theaters and at film festivals. Once the Residents began to perform live in 1982, however, the videos also began airing on the newly launched channel MTV and the influential late-night television program Night Flight. Like the group’s aural pastiche, their ‘expressionistic’ videos drew on the dark montage of John Heartfield as well as that of fellow Bay Area artists Bruce Conner and Wallace Berman. But the Residents’ samples and cut-ups managed to enter wider and more diversified streams of circulation, flouting institutional boundaries that the art world was just beginning to breach. The interlude became the centerpiece.

Music video arose as an interstitial arena in which to toy with popular modes of distribution – it was also the perfect field for testing new kinds of televisual celebrity. Paik had already presaged this with his audiovisual deformations of the Beatles, yet perhaps it was David Bowie who most forcefully exploited the music video to make the subcultural into the iconic. As Thurston Moore has observed, Bowie “burst into the psychosis of the young and restless intellectuals around the world” [1] with his outré art school look and mannered androgyny. And music video was the catalyst: Bowie’s canonical single “Space Oddity”, recorded and released to coincide with the first moon landing in 1969, uses this persona to tell the story of Major Tom, an astronaut who becomes lost in space. The five-minute video, made in 1972 (and originally shot on 16-mm film) for the track’s US release, opens and closes with what appear to be abstract waveform signals and extraterrestrial sounds of static; in between, a very young and colorfully lit Bowie is seen in close-up. Directed by Mick Rock (the photographer-filmmaker best known for his legendary shots of ’70s glam rockers), the clip would have been shown on Scopitone apparatuses-primitive 16-mm film jukeboxes-housed in bars and clubs. This precursor to the latter-day music video was, then, a kind of privatized conduit for rock-star fame, superseding rock magazines as the place where fans could connect with their idols. It should come as no surprise that at precisely the same time as the “Space Oddity” video, Bowie would assume the larger-than-life character of Ziggy Stardust, complete with what Moore has called his “alien rooster cut and spaceman glam gear.”

As audio and video technology advanced, and television was affected by MTV, artists reflected upon how commercial entities controlled mass communication and used technology to shape modern culture. Karen Finley, Dara Birnbaum, and Martha Rosler utilized this technology to criticize stereotypes of women promoted in the mass media, as seen in Birnbaum’s Pop-Pop Video (1980); an audio track by Finley, Tales of Taboo (1986); and a plate and track from Rosler’s print portion of the portfolio Artifacts at the End of a Decade (1981). The limits of technology and its potential as a tool for activism are explored by the video work of Tom Kalin, John Kelly, and Bob Beck, including Kalin’s video Nomads (1993), Kelly’s video Pass the Blutwurst, Bitte, #1 (1986), and Beck’s video Girlfriend in a Coma (1980). The wide distribution possibilities that video offered (and their continuation in today’s distribution through the Internet) are a cornerstone of the video-artist Seth Price’s practice. His video NJS Map (2001–02), which traces the genealogy of one period in pop music called “New Jack Swing,” is related to his ongoing project Title Variable, comprising several music compilations and published articles investigating technology’s impact on music production.

Four music videos projected in the following section exemplify the vigor and effort that were put into this new art form: Keith Haring making a hand-drawn, theatrical garment for Grace Jones in “I’m Not Perfect (But I’m Perfect for You)” (1986); Diamanda Galás channeling both performance art and goth metal for “Double-Barrel Prayer” (1988); Long Island–based duo Eric B. and Rakim’s extensive sampling from James Brown awakening other hip hop interest in “The Godfather of Soul”; and the video for A Tribe Called Quest’s “Scenario,” highlighting the band’s playful and humorous approach to hip hop.

After the second wave of the Feminist Movement in the United States in the late 1960s and 1970s, so-called third-wave Feminism emerged from its point of genesis, the riot grrrl capital Portland, Oregon, in the 1990s. Inspired by the ethos of DIY (Do-It-Yourself), young women formed impromptu punk bands; wrote, pasted together, and photocopied self-published zines; and created their own independent methods of distribution. Several examples of those zines are on view. Performance artist and media-maker Miranda July founded Joanie 4 Jackie (originally Big Miss Movieola) in 1995 as an informal organization and active network, compiling video chain letters that gave young women the courage and confidence to continue making movies; a related poster and zine are on view in the gallery. A recording by Le Tigre also plays at an audio station; the band fused New Wave, electronic dance music, and the angry punk sound of the riot grrrl era with humorous lyrics to confront such social ills as police brutality and Mayor Rudolph Giuliani’s crackdowns in millennial New York.

In this era of genre-crossing, many musicians were active participants in the art scene, and vice-versa. Sonic Youth worked with artist Tony Oursler on the video for “Tunic (Song for Karen)” (1990), which plays on a monitor in the exhibition. Tony Conrad, a film, video, and sound pioneer and composer, formed the art band XXX Macarena with fellow artists Jutta Koether and John Miller. Conrad’s video In Line (1986) is joined by a record sleeve from XXX Macarena. Fisherspooner, an electroclash performance duo that formed in 1998 and frequently performed in art galleries, skewered retro electropop and early Pet Shop Boys in their action-packed events, and the record sleeve from their album #1 (2001) is on view.

The rise of computer culture and wider access to new technologies in the mid-1990s brought with it a host of new possibilities for artists to explore. The three interactive pieces on display are examples of how artists harnessed new tools to bring audiences into their work. Via an interactive CD-ROM, Puppet Hotel (1995), visitors have access to performance artist/composer Laurie Anderson’s modified violins, and are invited to play a tune. A CD-ROM by the Residents, Freak Show (1994), makes the answering machines and private diaries tucked away in freak show performers’ caravans available. In Perry Hoberman’s Faraday’s Ghost (2000), a bar code wand activates the distinctive sounds of everyday appliances – toasters, radios, and vacuum cleaners.

Art video and music video thus met in an unruly fashion in the ’70s, but they would soon arrive at the type of conjunction we think we know best: MTV. The advent of MTV was a no less heterogeneous affair, its beginnings stirring in both the celebrity-driven commodification of music and the aesthetic testing of perception. The station actually presented brief “Art Breaks” that it commissioned from artists such as Jenny Holzer. But other videos not labeled as such were equally vanguard: Think of the wittily mordent Devo, or of Laurie Anderson, who made her renowned music video “O Superman” for Warner Bros. Records in 1981 – just in time for the start of MTV. Multimedia artist Perry Hoberman (who had been turning obsolete technologies such as 3-D slide systems into droll animated narratives) joined Anderson as artistic director. Accommodating the consumer TV set’s small scale, they concentrated on close-up shots of Anderson, exaggerated silhouettes of her shadow-puppet hands, and her glowing face, illuminated by a tiny pillow speaker placed inside her mouth that emanated a prerecorded violin solo that she modulated with her lips. Anderson’s video aired in rotation in between both “Art Breaks” and ‘mainstream’ videos – the long duration and sustained sensations of past sonic and visual experiments now a series of fast gaps and fills.

Jump Cut Forward

As the personal computer permeated the consumer market in the early 1990s and the economy turned sour, artists turned again to funky homespun styles. Newfound accessibility to technology initiated a surge of innovative personal work – often interactive. Video and audio gradually morphed into media, as artists developed programming skills. Media moved in from the periphery and became mainstream contemporary practice. Sound emerged as a wide-open frontier. Super-sensitive microphones made possible the capture of previously unheard, underwater creature communication. Artists edited their digital sound files, which they projected through precision directional speakers. Audiences became careful listeners as they experienced inspiringly profound acoustic compositions in spatial installations.

Soundings: A Contemporary Score, the last show I organized at MoMA (August 10–November 3, 2013), featured recent projects by fifteen young artists who work with sound. They came from the United States, Uruguay, Norway, Denmark, England, Scotland, Germany, Australia, Japan, and Taiwan and had a broad understanding of art, architecture, performance, telecommunications, philosophy, and music. As they moved comfortably between mediums, listening and hearing remained central to their practices. Their environments, drawings and assemblages had a palpable sonic presence, even the ones that must be seen to be heard.

The work brought together in the exhibition reflected the strength of a dynamic and diversified area of contemporary practice. Some of the pieces conveyed sound visually. The sound they sparked in the mind’s eye (or ear) is sometimes referred to as non-cochlear sound, [2] a seemingly paradoxical term that recalls Marcel Duchamp’s notion of “anti-retinal art.” [3]

In an exemplary evocation of seen sound, Marco Fusinato produced five abstract drawings based on an orchestral score. Each drawing distilled one page of the score to a single note. If Fusinato’s piece were ever realized, the orchestra would perform the most complex five notes ever heard.

A more traditional rendering of a score was heard in a work by Susan Philipsz. Her installation drew upon a symphony that was composed in a concentration camp in Nazi Germany in 1943. Whereas the original score was written for twenty-four instruments, in the performance orchestrated by Philipsz, there were just two, a cello and a viola, playing only their intermittent parts in a work haunted by silences.

Field recording, a branch of sound art also known as acoustic photography and phonography, was used to capture a sense of space and place, and in doing so, it revealed that silences are anything but empty. Jana Winderen recorded the echolocation sounds made by bats while they navigated. She reduced the echolocations to audible levels and incorporated them with sounds of the insects that bats feed on. Jacob Kirkegaard’s single-channel audio-visual projection depicted, in four sequential segments, four deserted rooms at the abandoned site of Chernobyl in Ukraine. The sonic atmosphere of each room, punctuated by barely audible sound events – a drip, a creak – was recorded, then played back and re-recorded repeatedly on location. With the addition of each sonic layer, the recording gained in mass and volume, as if to broadcast the terrifying message of nuclear disaster.

The works of several artists in Soundings were based on sound-producing devices that were altered. Camille Norment removed the interior mechanism from an old-fashioned standing microphone and replaced it with a light that eerily invokes the shades and voices of celebrated performers of the past. Richard Garet converted a worn-out record player into a stage for another antique – a shiny glass marble. Together, the obsolescent device and vintage child’s toy performed a touching drama that gave rise to sounds rarely if ever fully attended to. Tristan Perich organized 1,500 tiny and unaltered speakers in a twenty-five-foot-long rectangular array on a wall, all emitting 1-bit buzzes and chirps. Listeners’ proximity, whether walking by slowly, standing back or up close, shaped their individual experience of what ultimately is a bountiful composition.

Soundings was the realization of a longstanding commitment to bring sound by artists into the Museum. It began in 1979 with Sound Art, an exhibition of works by three artists that was held in a tiny video gallery. [4] Due to the small size of the space, the works were shown one at a time, in rotation, for a couple of weeks each. The impetus for the exhibition came from the artists, who, with their counter-cultural convictions, were committed to working in a medium that went against the grain. Sonic work then had a candor, a do-it-yourself sense of experimentation; a testing of the limits of tools, of the artists themselves, and often of their listeners.

Within contemporary art, the energy of the counter-culture has dissipated, and sound is no longer marginalized as a medium. Nevertheless, artists are more than ever drawn to it, perhaps because it is still so full of potential, and not yet quite defined.

Today camera-equipped smart phones saturate the globe. Tools are accessible to all and the do-it-yourself spirit rules. Artists and ordinary users alike are producer-communicator, and viewer-receiver. They ply their apps and share data at lightning speed, as image and sound supersede words.

The world has changed so inexorably that technology is close to being a user’s co-equal partner. The relationship between body, experience, and cognition is vastly different.

A new two-tiered distinction has come into play. The center is drifting away from New York, London, and Tokyo, away from galleries towards sales at art fairs and on the Internet. A small group of collector elites sets the pace in the art world, which is tarnished by higher and higher sales prices. At the other end of scale, the young generation that grew up with media is going way out on a limb to take heterodox positions. They can be expected to appear out of left field with creative breakthroughs made through experimentation on a laptop at home or in novel shared workspaces that combine art, technology, social utilities, and science.

I am still engaged in my ongoing quest. I want to better understand how artists are using tools, especially at a time when ideas and content matter more than material formats. Post 9/11 and Fukushima, some artists do not feel bound by global identity and instead they find focus on the particulars of local experience.

Unlike the start of my career, I am older and artists are younger. Still I am as driven as ever to find out what artists are thinking and making.

Notes and References

[1] From Thurston Moore’s introduction on December 1, 2008 to a program of music videos the Bowie Estate donated to MoMA earlier that year.

[2] Seth Kim-Cohen, In the Blink of an Ear: Toward a Non-Cochlear Sonic Art (New York: The Continuum International Publishing Group, Inc., 2009).

[3] According to the writer Calvin Tomkins and others, Duchamp was the great anti-retinal thinker.

[4] The exhibition included the work of Connie Beckley, Julia Heyward, and Maggie Payne. It was followed by Terry Fox’s MoMA show, in 1980. It was preceded by Laurie Anderson’s 1978 Projects exhibition with her Handphone Table.